On Friday 22 March, I visited the ‘Side by Side’ exhibition in the Spirit Level at the Royal Festival Hall; a collaboration between the Southbank Centre, The Rocket Artists and the University of Brighton. The exhibition, pioneering in its promotion of inclusive arts in such a high profile institution, features an array of multi-disciplinary works including drawings, sculptures, paintings, film and music, and brings together a whole variety of inclusive arts groups from all over Europe.

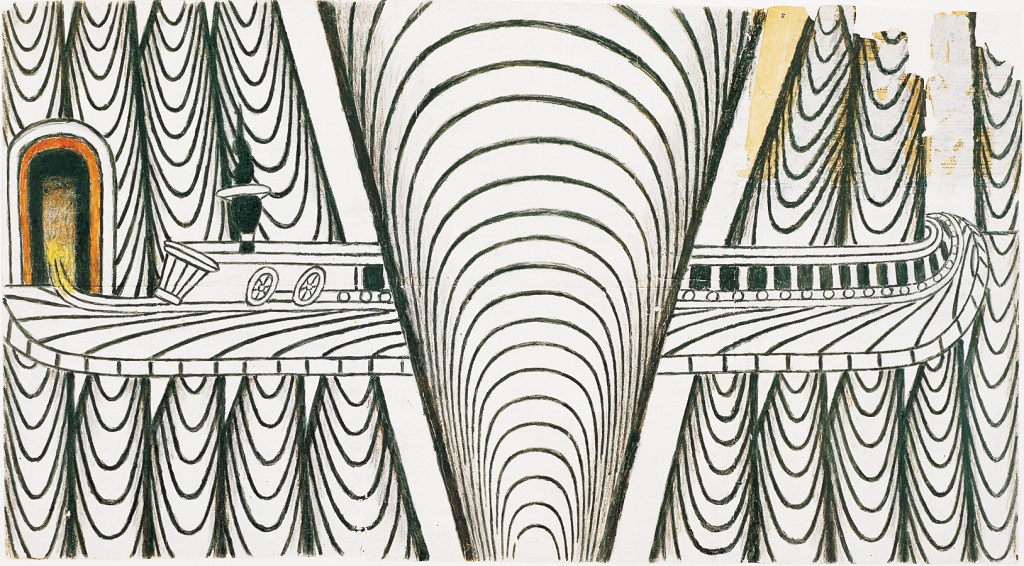

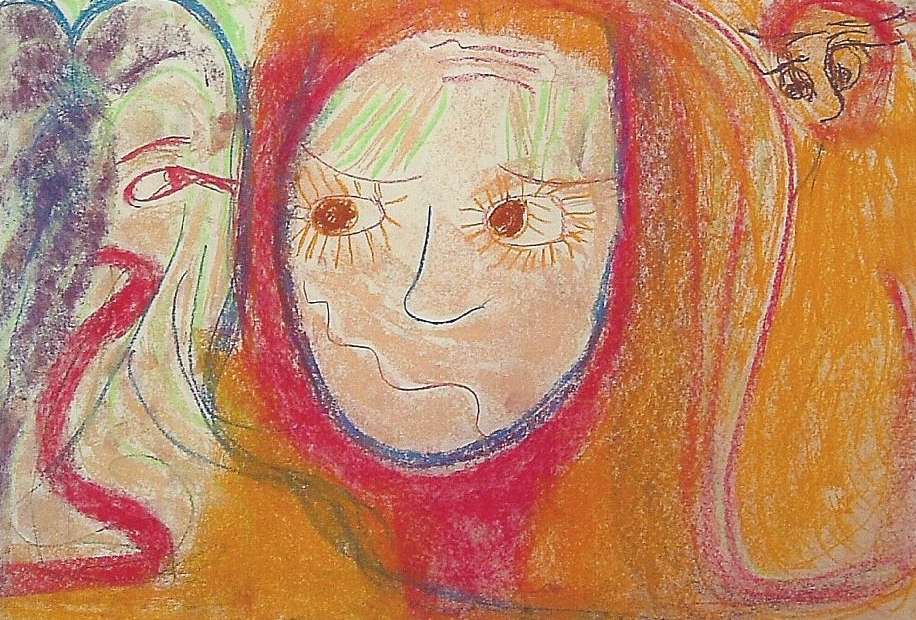

The exhibition is a warren of inspiration and awe; from modelled horses’ heads from Amsterdam, to glass jars filled with individual responses to a medical conference. One of my favourite parts of the exhibition is what I have called ‘the cardboard box area.’ This space consisted of a cardboard box tower with canvas works placed at various points around the sculpture – waiting to be discovered – as well as film projection and video. The rest of the works in the exhibition are equally exemplary, and are a treat for all of the senses. There is a sensual hanging piece, which invites you to be a part of it, paintings; black and white, colour, sculpture and tables and tables of beautiful creations, all displayed in a bright, spacious gallery.

The exhibition was accompanied by a Symposium, which I was lucky enough to be able attend. The Symposium was concerned with current inclusive arts practice and its progression, and provided a forum space in which both artists and their colleagues could discuss best practice and consider ways of thinking about art that aren’t directly related to written or spoken language. The outcome of the day was a collaboratively produced manifesto on what inclusive arts can and should be.

There were brief talks from Alice Fox (Rocket Artists, University of Brighton), Sue Williams of the Arts Council (who spoke about the Creative Case for Diversity) and Andrew Pike from KCAT (Kilkenny Collection for Arts Talent, Ireland), after which the group split up to participate in different workshops facilitated by various inclusive arts groups: Action Space, Corali Dance, Intoart, Project Volume, Stay Up Late, StopGap Dance Company and Rocket Artists. Each workshop covered a different ‘art’ e.g. visual art, dance, music…

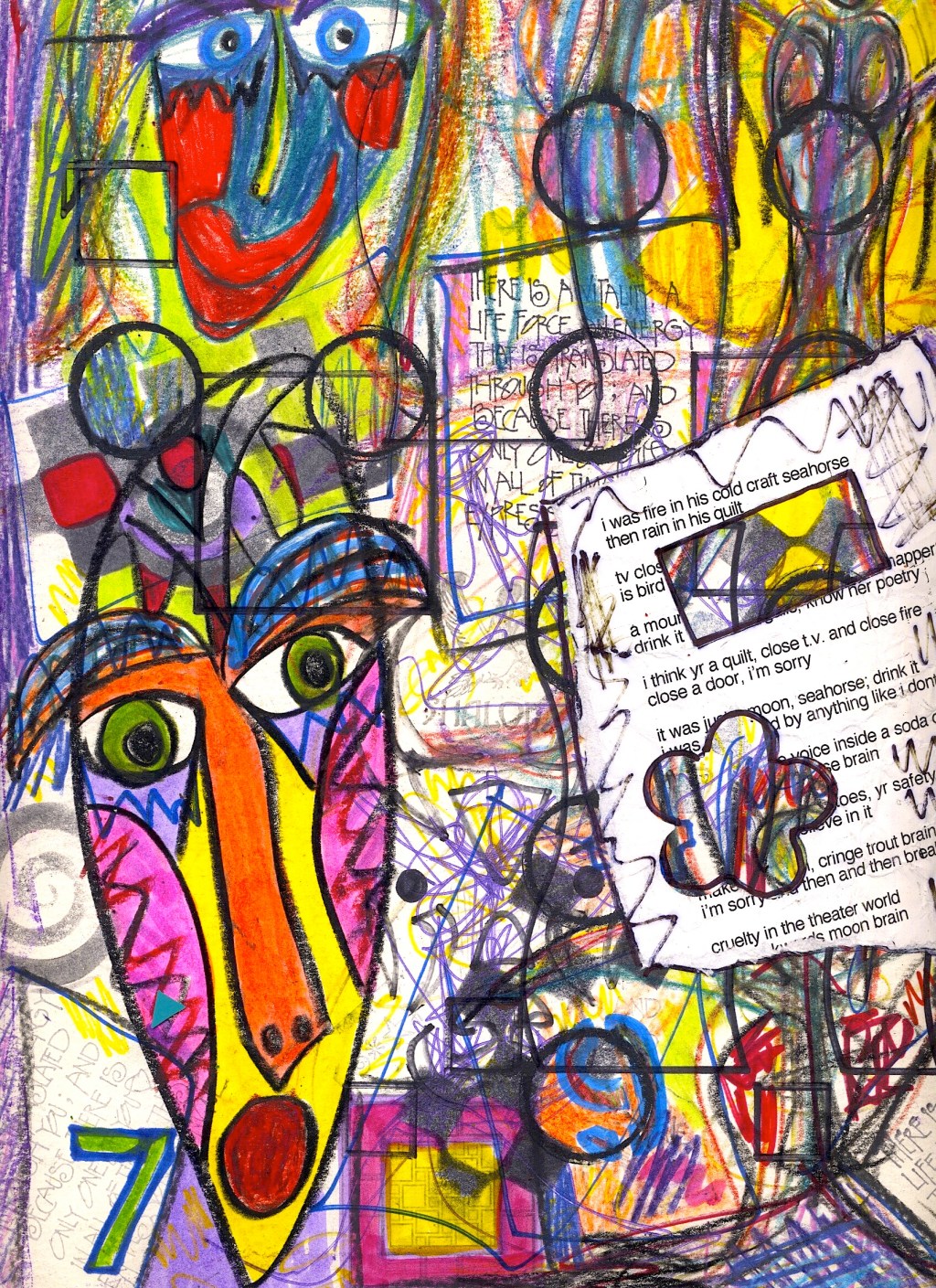

I attended the Rocket Artists’ ‘Say it with Bags’ workshop, which aimed to look at the use of language with regards to inclusive arts practice. For this workshop, we were asked to have a look around the ‘Side by Side’ exhibition and choose a piece that we were drawn to. Once we had decided on a piece, we then chose a word, movement and sound and created a drawing in response to the piece. This activity was designed to help us think about art in a more practical way – not just with words (whether spoken or written).

After the workshops, everyone reconvened to show/tell about the manifesto points that they had collaboratively created in the various workshops. Our group created two films to get our points across. Other groups used performance, dance, music or drawings to help illustrate their points.

What I understood the term ‘Side by Side’ to mean in the context of the Symposium and exhibition, was that the creation of this concluding manifesto was collaborative – a joint effort by the artists and those working with them. It was predominantly about creating a space to discuss/think about art in a more practical way – particularly for those who find traditional forms of communication difficult. It was about raising the status of the artist to the same level of those working with them.

Conducting some research into the project has highlighted the aims it is trying to achieve – these are:

- To establish a platform in a mainstream art space for leading and best practice organisations.

- To present a range of inclusive practices that span visual art, performance, music and film.

- To build a picture of what constitutes good/innovative practice with reference to Inclusive Arts.

- To highlight the process of collaboration as creating a space for equality.

- To create a platform and catalyst for future artistic collaborations between artists and groups.

The symposium really acted as a forum about the current state of Inclusive Arts in the UK and how this can be moved forward. The main questions we were encouraged to think about were:

- What lies at the heart of the experience of the creative, collaborative process?

- What conditions are necessary to enhance the collaborative process?

It was very much about everyone being involved in the workshops on the same level – both the artists and those they work with. So, overall, I think the phrase ‘Side by Side’ was used to express the idea of collaboration, and to eliminate the idea of there being a difference between the ‘teacher/workshop leader/arts facilitator’ and the artist.

I would be really interested to hear from others about their views on inclusive arts practice, so if you have any thoughts, please leave them below.

The ‘Side by Side’ exhibition is running at the Royal Festival Hall until 5 April 2013. For more information, click here. For more information on the project itself, click here.