Has the time finally come to erase the term outsider art? Its all-encompassing – and negatively perceived – character divides many people. I have personally been edging ever closer to this idea over the past few years. However, in perhaps a somewhat hesitant, cautious U-turn, I have been coming round to the idea of using the term outsider art more freely – in a ‘reclaiming’ kind of way. Rather similar to the way the term ‘disability arts’ has been reclaimed. If we are able to reclaim and redefine the term, it could be a powerful vessel through which we can promote work by artists outside of the mainstream. It could be the basis of a community which includes people from all over the world, from a huge number of different cultures and backgrounds. For artists who work predominantly alone, or artists who are not linked to a wider art community or network, it could provide a lifeline, a point of identification, confirmation.

The idea of ‘reclaiming’ a term is something that is becoming increasingly common in all parts of the world and is strongly linked to the idea of identity. Paula M. L. Moya in ‘Reclaiming Identity’ undertook the task of reclaiming identities because they are “evaluatable theoretical claims that have epistemic consequences. Who we understand ourselves to be will have consequences for how we experience and understand the world.”[1] After all, words aren’t bad, or derogatory; it is the meaning we imbue them with that makes them so. Are we able to change the negative meaning of words; flip them on their head and imbue them with positivity?

Whilst researching for this post, I read a fair few texts about identity, which recognise two camps when it comes to derogatory or unfavourable terms: the Absolutist and the Reclaimer. The Absolutist thinks that the only way to overcome the negative connotations of certain labels and phrases is to eradicate them completely, whereas the Reclaimer asserts that certain terms “mark important features of the target group’s social history, and that reclaiming the term – making it non-derogatory – is both possible and desirable.”[2]

So, if we relate this to outsider art, we can see that many camps are actively trying to discourage use of the term – the Absolutists. But, Hendricks and Oliver in ‘Language and Liberation’ assert that we can use the term in our favour. We are able to “detach the semantic content of the term from its pragmatic role of derogation, and it is desirable because doing so would take a weapon away from those who would wield it and would empower those who had formerly been victims.”[3] So, if we follow their theory, we could take the power away from those who currently hold it – perhaps this is the dealers, curators; high end art world people, and give it back to the artists. It could become a unifying term so that artists working outside of the mainstream with little to no contact with other artists or art networks can feel a part of something, a sense of belonging and validation, and perhaps even a sense of affirmation that they are, in fact, artists.

– Kate Davey

I would really like to hear what you think about the idea of the reclamation or eradication of the term outsider art in the comments below. Obviously, there is far more reading to be done into ‘identity’ and reclamation, but hopefully this is a starting point.

References

[1] Paula M. L. Moya, Reclaiming Identity, http://clogic.eserver.org/3-1&2/moya.html

[2] Christina Hendricks and Kelly Oliver, Language and Liberation: Feminism, Philosophy and Language, State University of New York Press, 1999, p42

[3] Ibid.

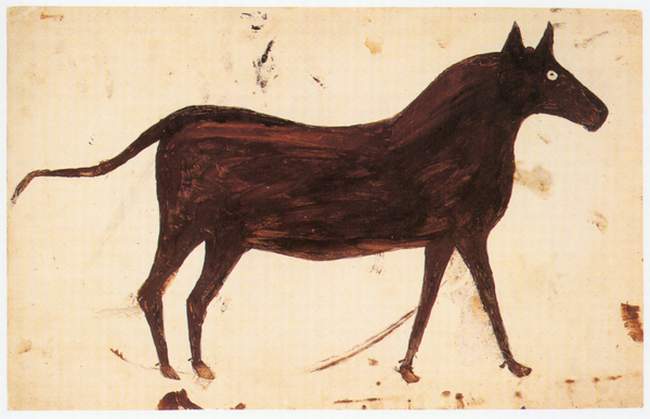

Featured image: James Castle