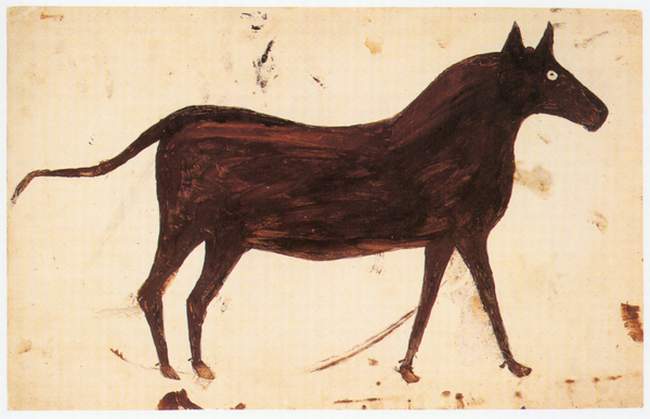

Above image: Bill Traylor, Brown Mule, 1939 (source: www.petulloartcollection.org)

“Categorisation is something that we do naturally and unconsciously every day. We recognise one animal as a cat and another as a dog. We organise objects in the world around us in ways that reflect these categories. In our kitchens, we keep baking trays with other baking trays, saucepans with other saucepans and keep food separate from cleaning products. We categorise ideas, people, tasks and objects. Categorisation is fundamental to the way we think.” – James Sinclair, 2006.

As humans, we categorise things to make sense of the world; we link new things to past experiences, and we group similar people or ideas. We group genres of books in the library. We archive our emails in labelled folders. If we did not do this, we would “become inundated by our environment and unable to cope.”[1] This is a poignant theory with regards to the relative ambiguity of Outsider Art.

I am not sure if you have heard of the fictitious taxonomy of animals described by writer Jorge Luis Borges in 1942. It looked at the work of John Wilkins; a 17th-century philosopher who proposed a new language that would parallel as a classification system. Borges wanted to illustrate the arbitrariness of such a way of categorising the world, so used an example of a taxonomy taken from an ancient Chinese encyclopaedia entitled ‘Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge.’ The list described in the encyclopaedia divides animals into one of 14 categories:

- Those that belong to the emperor

- Embalmed ones

- Those that are trained

- Suckling pigs

- Mermaids

- Fabulous ones

- Stray dogs

- Those that are included in this classification

- Those that tremble as if they were mad

- Innumerable ones

- Those drawn with a very fine camel hair brush

- Et cetera

- Those that have just broken the flower vase

- Those that, at a distance, resemble flies.

Quite ridiculous, right? It is a similar story for the huge list of terms we have that fall under the umbrella of Outsider Art (not quite so ridiculous, but probably equally as long). Here are just a few that I have come across at some point: self-taught art, visionary art, primitive art, naive art, marginalised art.. etc. etc. Sometimes giving things labels help us make sense of them, but it can also mean we end up generalising about people or situations that, actually, we have absolutely no idea about.

I have written before about my position on the debate with regard to the term Outsider Art. I sit somewhere between thinking we should not need it, and thinking that to have a label means that people recognise it. Particularly people who have not been aware of it before. We have seen, more so in the last year, an exponential increase in awareness of the subject (particularly in the UK, thanks to a number of high profile London-based exhibitions on the subject). Now, when I tell someone what I blog on, they have some idea what I am talking about. And surely, this can only be a good thing. Raising the profile of this art is of course number one on my agenda. But following close behind is number two on the agenda: to eliminate the discriminatory and redundant term used to describe it. It is a double-edge sword, it seems; raising people’s awareness of a term that one day we hope to be rid of.

Outsider Art is one of those terms that would fit into that ‘other’ tick box you get on forms, or your ‘miscellaneous’ email folder. It is where everything that cannot be neatly categorised can be bundled up, and we can smile, thinking we’ve hoovered the dust up. Everything is in its place. But it is this attitude that means that it is becoming increasingly difficult to break open Outsider Art and get people to actually think about what they are grouping together. To put it crudely, we are grouping people diagnosed with mental health issues with ex-offenders, ex-offenders with those who have not been to art school, and those who have not been to art school with artists who paint or draw in a way that is not similar to what we conventionally consider to be art. We are, in essence, grouping people. Is this not the same as those sweeping generalisations that go against our twenty-first century ideas about acceptance, inclusivity, and political correctness? Do all women like the colour pink, all men like cars and sport? I do not recall other types of art being categorised in this way. Surely this in some way goes against our innate need for categorisation, because – like the Chinese encyclopaedia – it does not make any sense.

To move forward, we need to continue to break down the barriers around what we consider to be Outsider Art. We need to have open conversations about what it is, where it is going, and what it all means. But then we need to consciously think about – as humans with innate needs – how we can better categorise the work under this umbrella. I, for one, have not figured this out yet, but I feel like we are making some progress simply by raising awareness about it. It feels like the first step on a ladder that looks a little something like this: Awareness > De-constructing > Re-constructing. And maybe the re-construction of the category will provide evidence that we actually do not need such a term – we will realise that the work of ‘Outsider Artists’ actually fits within the ‘accepted’ canon of art history; after all, all art made in the past is, by its existence, the history of art.

Let me know what you think in the comments below, or on Twitter: @kd_outsiderart

References

[1] Kate Griffiths, ‘The Role of Categorization in Perception’, 2000

Leave a reply to Brian Gibson Cancel reply