On 31st May, I was very kindly invited to give a talk at the ‘Life is Your Very Own Canvas’ mid-exhibition event in Aberdeen by organiser of the show, Steve Murison. The exhibition showcased work by people who are part of the Penumbra Art Group in Aberdeen. I spoke briefly about outsider art and how I had become interested in it, and what I was doing now to support artists who might be considered ‘outsider.’ Although the talk was brief, I took some time in the run up to refresh my memory on all things outsider art – which I thought I would put together in a blog post.

My prior research took me back to when I first starting studying outsider art – right to the beginning, to quotes from Jean Dubuffet and Roger Cardinal. I’m going to split this post into four different sections, just to put my thoughts down on paper (or computer): a brief history of outsider art, what it is today, my interest in outsider art, and what I think about outsider art now.

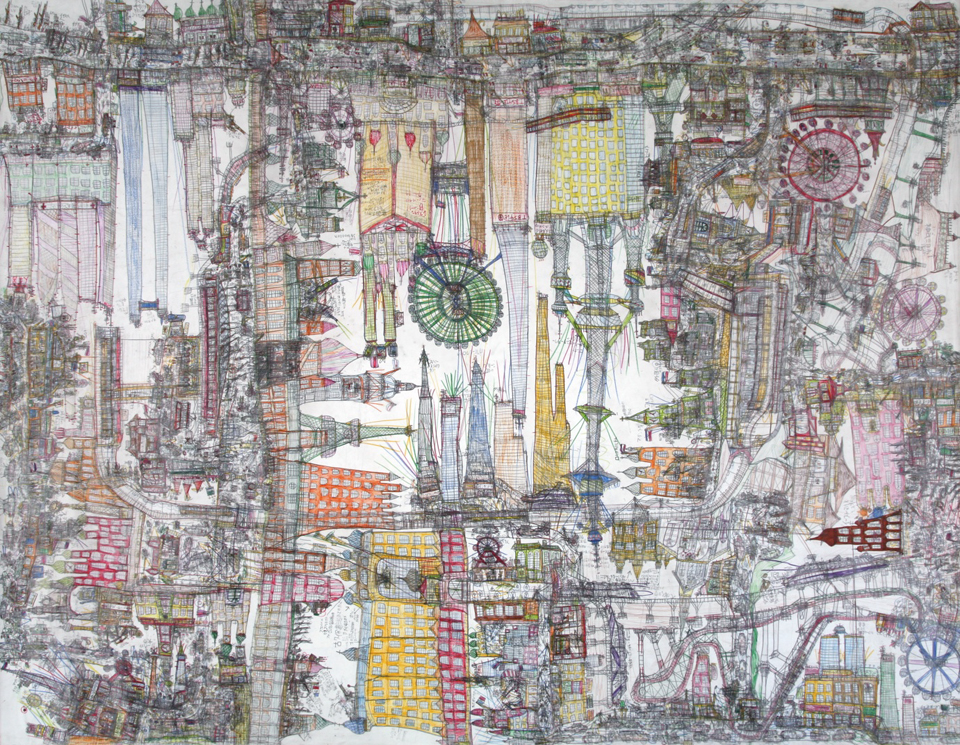

First things first, the exhibition was absolutely extraordinary. Many of the artists with work on the wall had never picked up a pen or a paintbrush before joining the art group, and many had re-found their creativity many years after losing it to illness or life events. There was a mixture of 2D pieces, including a series of ‘diary drawings’ illustrating the artist’s daily life in and around the city of Aberdeen, and 3D pieces; like a jaw-dropping papier mache dragon. It was inspiring to meet many of the artists at the event, who were all incredibly proud (as they should be) at having their work hanging in the exhibition.

The History

So, let’s start at the beginning. The initial emergence of outsider art occurred between the ‘Golden Years’ of 1880 and 1930. The term itself was coined by art historian Roger Cardinal in 1972 as an English equivalent to Jean Dubuffet’s ‘Art Brut’ or Raw Art, which was coined in the 1940s. When describing work as ‘Art Brut,’ Dubuffet meant work that was untouched and untainted by traditional artistic and social conventions. In his manifesto Art Brut in Preference to the Cultural Arts (1949) he says:

“We understand this term (Art Brut) to be works produced by persons unscathed by artistic culture, where mimicry plays little or no part. The artists derive everything – subjects, choice of materials, means of transposition, rhythms, styles of writing etc. – from their own depths, and not from the conventions of classical or fashionable art.”

Dubuffet’s collection of Art Brut is housed in the Collection de L’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, for which there is (still) a very strict acquisitions criteria. The museum’s acquisitions are based on the following five characteristics: social marginality, cultural virginity, the disinterested character of the work, artistic autonomy, and inventiveness. There are, of course, contentious ideas within Dubuffet’s strict – and marginalising – criteria. It is incredibly difficult, even so in the early 20th century, for someone to be completely detached and separated from culture in all its forms.

Take for example some of the most famous outsider artists. Adolf Wolfli worked as a farm hand in his early life; Scottie Wilson was in the armed forces, travelling to both South Africa and India; and Henry Darger worked for most of his life as a caretaker.

Dubuffet’s Art Brut is idealistic, it is not realistic. And this is where some of the contentions and debates arise around the term and what it stands for – back then and still today.

Outsider Art in the Present Day

Throughout the 20th Century, the term gradually gained momentum. It is still around today, although in a very different form to Dubuffet’s Art Brut. Today, it is more of an umbrella term for work that is created outside of mainstream culture – and includes terms like ‘self-taught art,’ ‘folk art,’ ‘intuitive art.’

Everyone in the field has their own idea of what it means – a popular one being that anyone who calls themselves an outsider cannot be considered an outsider artist. Originally, outsider art was taken from the homes of artists on the sad happening of their death (like the famous story of Darger whose work was found when his apartment was cleared following his death, whence his tomes of The Vivien Girls books were uncovered).

And then, of course, there is the divide between mainstream and ‘outsider’ art. At what point does an outsider artist become an ‘insider’ artist? Dubuffet was known to have ‘ex-communicated’ one of his own discoveries, Gaston Chaissac, because of his contact with ‘cultivated circles,’ and Joe Coleman was expelled from the 2002 New York Outsider Art Fair in which he had taken part since 1997 because he had been to art school and had ‘become too aware of the whole business process of selling.’

A good way to look at it, I think – as it gets very confusing – is how Editor of Raw Vision Magazine, John Maizels talks about it in his book Raw Creation: Outsider Art and Beyond (1996):

“Think of Art Brut as the white hot centre – the purest form of creativity. The next in a series of concentric circles would be outsider art, including art brut and extending beyond it. This circle would in turn overlap with that of folk art, which would then merge into self-taught art, ultimately diffusing into the realms of so-called professional art.”

My Journey with Outsider Art

My own interest in outsider art first started when I was at university. I studied History of Art, and – surprisingly – we had a whole module on outsider art. Well, it was actually a module on psychoanalysis and art, but the term outsider art kept cropping up, and I was curious. To help with my paper for this module, I visited Bethlem Museum and Archives to look at the work of Richard Dadd. I immediately found myself immersed in this world of raw human creation.

Outsider art for me often comes straight from within. It’s not made for a market and it doesn’t come out of art schools (although I am certainly not adverse to people who have been to art school aligning themselves with outsider art). It inspires me because one of the most innate and unique things about being a human being is our ability to be creative. I think there is nothing that illustrates this better than outsider art.

I went on to write my BA Hons dissertation on the links between German Expressionism and outsider art and was not surprised to find that many art movements in the twentieth century were inspired by the work of outsider artists – including the Surrealists and German Expressionists. Artists at this time wanted to capture the intuitive spontaneity of this work to represent the turbulent times they were living through.

I went on to study for an MA in Art History and by this point was focusing solely on outsider art. I wrote my extended dissertation on the ethics of exhibiting and curating work by outsider artists. For me, it was interesting to think about how ethical it is to display work by someone who never intended for it to be seen. I would think about Henry Darger and his Vivien Girls. He had created this whole world in private – surely it should have been kept private? But if it had been, we wouldn’t have had access to this astounding feat of imagination – maybe the books would have been destroyed?

I continued my research, thinking about the different ways the work could be displayed to best exhibit its aesthetic and inspirational qualities. Should interpretation include a note on the artist? Should the work stand on its own? There seemed to be so many questions that kept on breeding more questions.

Ever since I finished my MA four years ago, I have been working with various projects and organisations that promote or support artists facing some kind of barrier to the art world – whether that barrier is their health, disability or social circumstance.

What do I think now?

For me, the term outsider art should be redundant. It shouldn’t be outsider art – it should just be art. Sometimes, people and artists need a little bit of extra support to get their work out there, and for this reason I think it’s vital to have organisations and projects like Outside In and Creative Future, but I think the next chapter is to challenge the impenetrable art world.

Why is it so difficult for people to break into the art world if they haven’t been to art school? Who gets to choose what is and isn’t art? For me, outsider art is the bravest form of art. It is defined by artists exposing themselves on paper, in clay, on film, in words, and then sharing it with the world. It’s all about creativity, raw intuition, and the uniqueness of being human – and it can certainly teach us all a lot about humanity!