Following on from my previous post – which was more of an announcement that there will be more posts soon – I want to just further contextualise my research with the hope of identifying for you its purpose and what I hope it is able to achieve. Ultimately, I hope you can find something new or something useful that can help in your advocacy for outsider art or, if you are an artist yourself, can help you understand why your experience of navigating the UK cultural sector may have been particularly challenging.

I want to preface this post by acknowledging that I don’t have lived experience of being an outsider artist, something that I think would have made someone better placed to do this, but I have spent my career working closely with artists and organisations across this field. I was fortunate that my PhD was fee waived by the University of Chichester and that I had supportive employers who made it possible to continue working full-time whilst researching. Like many, I couldn’t have done it otherwise. For me personally, this research has been a long time coming – it’s something I’ve carried with me since the start of my career – and I hope that my determination to make space for it, even with limited time and capacity, shows how deeply I care about this work.

Ultimately, I hope that this research can be for everyone: for all the incredibly talented and ambitious artists I have worked with over the years; for all the amazing studio workers, support workers, curators and volunteers who spend their everyday supporting artists and challenging the systems that exist within the art world; and perhaps most of all, for every individual who has ever questioned their own talent or creativity – for every person who has said that they remember the joy of being creative as a child, but as they got older, were told (by parents, by teachers, by the world) that it was just a hobby, or that they weren’t any good at it. Our creativity is what makes us human, and I hope my research shows that it is never our creativity or our talent that is in question – it is the systems that exist around us, systems that we so often have such little control over.

Six years ago, when I set out to identify what I wanted my research to focus on, I returned to a quote from David Maclagan’s Outsider Art: From the Margins to the Marketplace (Reaktion Books, 2009), in which Maclagan states that “what began as a radical antithesis to accepted forms of art cannot go on forever being ‘outside’ the culture from which it once claimed to be independent: despite initial scepticism or hostility, Outsider Art is gradually being assimilated. Exhibitions and publications devoted to it multiply, galleries and museums acquire it, and it has also undoubtedly influenced many contemporary artists: so the gap that once separated it from the art world has narrowed.” (p7-8)

It is true, in many ways, that in more recent years outsider art has had increasing recognition from more mainstream sources. This is illustrated in the nomination of Project Art Works for the 2021 Turner Prize (and even more recently, the nomination of Nnena Kalu for the 2025 Turner Prize!), and in the increase in key exhibitions centred on outsider art hosted at major institutions in the UK (Wellcome Collection 2013, Hayward Gallery 2013, Barbican 2021). However, when I returned to this quote after almost ten years of working with artists who may be seen as ‘outsiders,’ I realised that Maclagan’s quote did not illustrate my experience – or the artists’. As I have navigated my way through the waters of the art world in a professional capacity, it became important (almost crucial) for me to underline my anecdotal experiences with what I could only describe as evidence – or a solid foundation of research.

My hope is that is what this research has done. Because it has shown that there is an illusion of inclusion in the art world. On the surface, yes, we could be forgiven for going all in with Maclagan on this one – we can see outsider art around us more than we ever have before. But the research shows the reality And that reality is that there is still an evidenced disparity in the treatment and reception of outsider art and mainstream art in the UK.

It shows that this disparity is four-fold: firstly, it is because of the ongoing contestation and stigma around the term ‘outsider art’ itself; secondly, because of outsider art’s continual relegation to peripheral spaces (both physical – when it appears in ‘community’ galleries or ‘education’ spaces – and conceptual – when it is shown or support as part of the arts and health agenda); thirdly, because the UK art world continues to lack diversity among its leaders and decision-makers; and finally, because the art world machine and its institutional structures work to exclude art that does not align with our cultural or historical norms.

These findings are based on the analysis of 35 semi-structured interviews conducted with artists, ‘outsider arts’ professionals and ‘mainstream’ curators. Over the next few posts, I will go in depth into each of the findings in what I hope is an accessible way. By identifying the factors that continue to contribute to the disparity in the treatment of outsider art – and how these factors have been able to persevere – I hope that we can all take a more knowledgeable and mindful approach to exhibiting, writing about, showcasing, celebrating, sharing and making art.

A note on the use of the term ‘outsider art’

It is important for me to explain my usage of the term ‘outsider art’ in this context because I know it is divisive and ultimately has stigmatising and marginalising connotations. But the term has played a central role in the experience of this type of art, and I use it only because several of the artists I interviewed as part of the research noted that they found a sense of affinity with the label. Therefore, by not continuing to contest, question or disparage it, I hope that I am not continuing to gatekeep it.

It is used with heavy acknowledgement that it is not perfect, and that it has expanded exponentially from what it once was. I use it with the hope that by leaving questions about the term to one side for the moment, we can give that time to the art and the artists instead. And there is hope too, the research shows, that artists can ‘take back’ the term – which for many has provided a space and place of belonging in a world where they feel like they don’t really belong anywhere.

Join me again soon for the next post, which will focus on the first key factor identified in the research – the implications of the term itself, and how this has had an impact on the reception of outsider art.

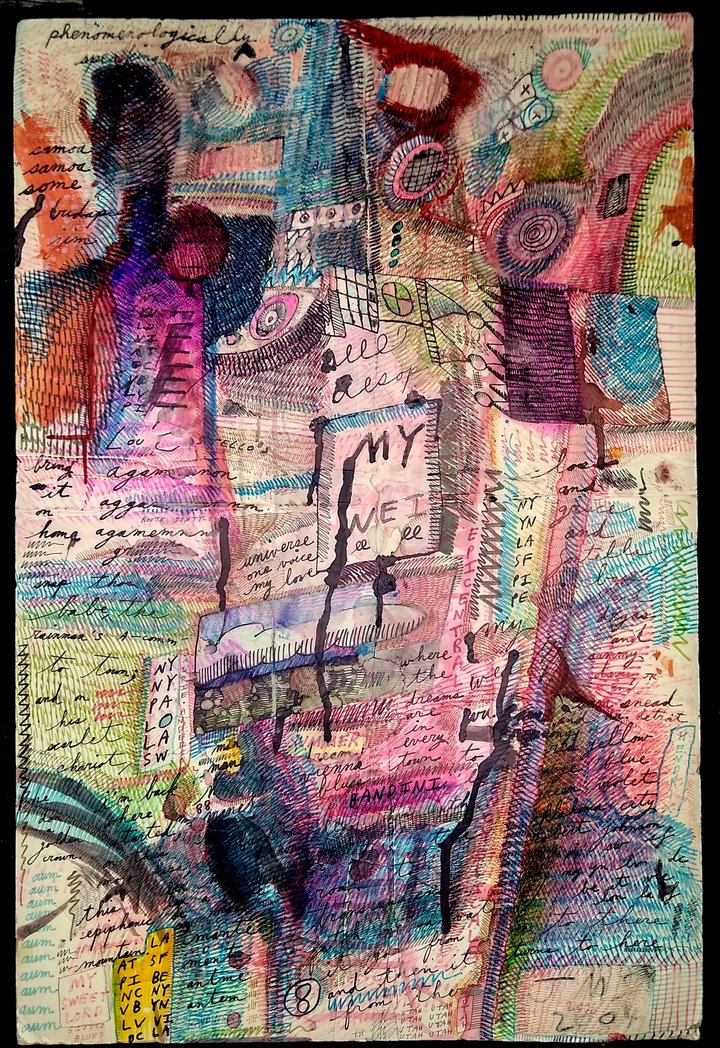

(Featured image: Jon Sarkin, Phenomonologicall)

Leave a comment