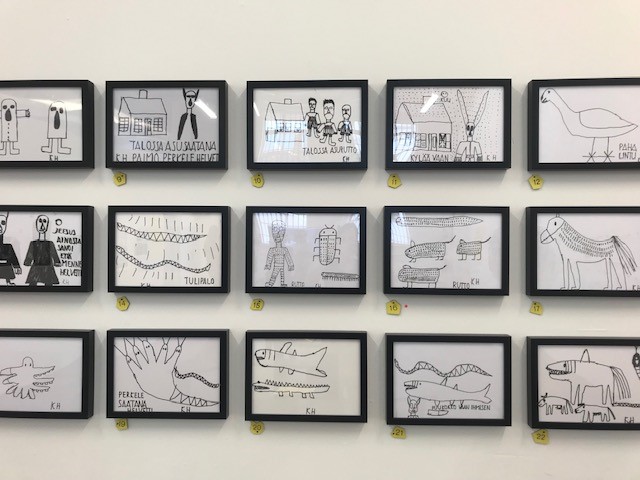

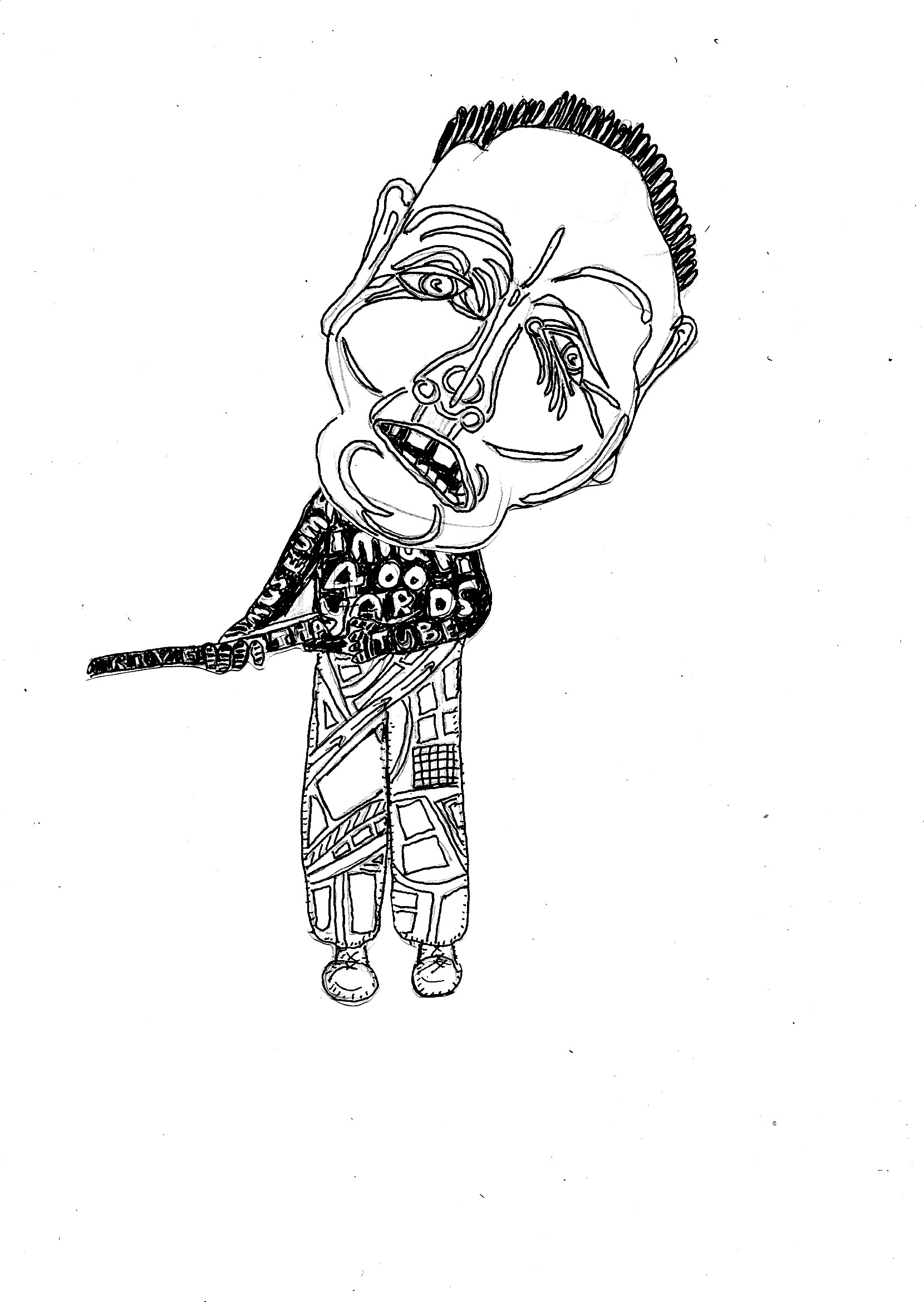

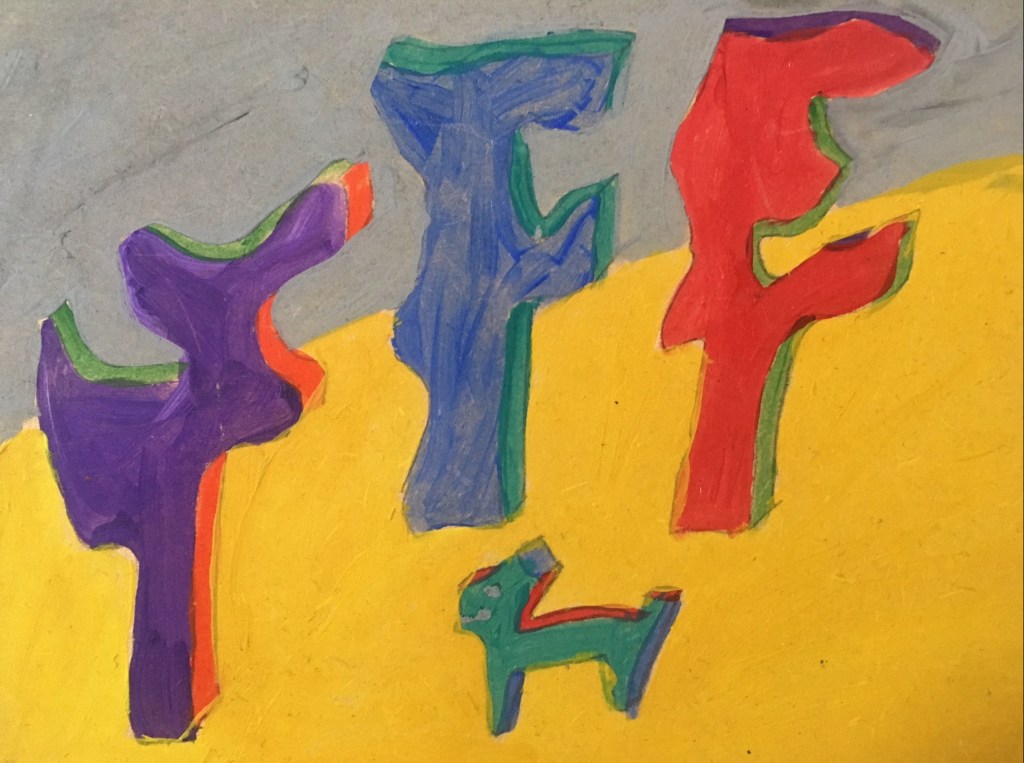

Earlier this month, I was lucky enough to be invited to join a panel discussion in London organised by Pertti’s Choice in my role as Step Up Coordinator at Outside In. The panel focused on the issue of ‘sustainable arts careers for people with disabilities.’ It chimed nicely with the work I do on Outside In’s Step Up training and professional development programme, which ultimately aims to challenge who is able to take up positions of authority in the art world. I was joined on the panel by Ese Vienamo, who works for the Arts Promotion Center in Finland focusing specifically on ‘outsider art,’ and Sami Helle, from Finnish band Pertti Kurikka. In this post, I wanted to outline some of the topics we covered during the discussion, and reiterate some of my key thoughts.

I started by introducing the current system in the UK, which really highlights the work that needs to be done in recruiting people with disabilities to positions within the arts sector. Arts Council England (ACE)’s 2015-16 Equality, Diversity and the Creative Case report showed that only 4% of staff at National Portfolio Organisations and Major Museum Partners were disabled, compared to 19% of the general population. These figures highlight the ongoing under-representation of disabled people in the arts sector, despite ACE and and other organisations’ attempts to diversify the arts workforce.

The challenges we face in the UK arts workforce, to me, are defined by a system that has existed in the same, traditional way for a number of years, but is no longer fit for purpose – perhaps has never even been fit for purpose. We expect people (whatever their background or situation) to fit into this existing system, rather than offering a flexibility that can accommodate people who have different needs or requirements. The arts sector is notorious for its long hours and low pay, and is structured in a way that if someone, for example, struggles to travel at rush hour, this might put them out of the running for a job that they would otherwise be perfectly competent at. I think this is epidemic throughout the UK workforce more generally (the 9-5 working week, for example, is not suitable for everyone), but in the liberal world of the arts, which actively encourages and seeks out diversity, we should – and can – expect more.

As a sector, our inability to diversify our workforce leads to a vicious cycle that continues to create an elite system that many cannot gain entry to. The majority of people working in the arts are from a white, middle-class background, as highlighted in the Department for Culture, Media and Sport’s ‘Creative Industries: Focus on Employment’ report in 2015, which shows that in 2014, 91.9% of jobs in the creative economy were held by people in more advantaged socio-economic groups, compared to 66% of jobs in the wider UK economy. People tend to ‘seek out their own,’ and this means that much of the art we see in galleries, theatres, cinemas, is created by and for people from a white, middle-class and able-bodied background. This is an issue I feel very passionately about because I think as a nation we are missing out on inspiring, innovative and stimulating art simply because we are not able to open our minds to different ways of working.

We are dealing with challenges like ingrained preconceptions about people with disabilities, people from low socio-economic backgrounds, and people with mental health issues, as well as a system that is structured in such a rigid and traditional fashion. We need to come together to challenge both of these things in order to create significant and lasting change, and this should be happening from the ‘bottom’ and the ‘top.’ Change is difficult, and it takes time, particularly if there is a system that has existed historically. We need to be approaching this from the top-level (government, CEOs, the big arts institutions), and from the bottom (working with individual organisations to think about diversifying their workforce and how this can be done in a manageable way).

Discussions around these issues have certainly been started, but there is a long way to go. As a sector, we need to change our mindset, see flexible working as the norm, and certainly start seeing the diversification of the workforce as something that will enrich our artistic output, rather than as something that is tokenistic and needs to be done to ‘tick boxes.’

Making these changes starts on an individual level, at each and every arts organisation in the UK. Change doesn’t start at the interview process, or even the application process. It starts before that. It starts with the language we use in job descriptions and person specifications, it starts with where we advertise our jobs, and it starts with a different mindset that is actively seeking out perspectives that are different to our own, ingrained narratives. It starts with flexibility – how can people apply for a job (do they have to fill out an application?), can the interview location be flexible? Can the time and date of the interview be flexible? Is there flexibility in the role itself for the right person, and is this outlined in our advertising. We need to be working with people who might not be able to fit into the existing system for whatever reason to help make the system work for them.

So, my final word – let’s stop assuming that we should be moulding everyone to fit into the same, broken system, and instead, start actively thinking about we can be changing this system (even in the tiniest way). It is not a one-size-fits-all; it takes communication and flexibility. Because after all, a more diverse workforce = more diverse art.

![20190308_134202~2[1]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/20190308_13420221.jpg?w=1189&h=1743)

![20190405_152638~2[1]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/20190405_15263821.jpg?w=1754&h=1156)

![20190405_152709~2[1]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/20190405_15270921.jpg?w=1112&h=1578)

![20190405_152717~2[1]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/20190405_15271721.jpg?w=1542&h=1158)

![20190308_134212~2[1]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/20190308_13421221.jpg?w=1185&h=1672)