Flash of Splendour Artists

Flash of Splendour Artists @ Threadneedle Street, London

Ongoing

Flash of Splendour Artists is a “groundbreaking and highly acclaimed not-for-profit creative arts organisation working with music, poetry and the visual arts to effect societal change.”

The exhibition itself will focus on the work of 5 young British artists who are mentored by Flash of Splendour Arts.

The organisation itself specialises in “fostering creativity and self-determination in children and young adults, with a passionate interest in empowering those disempowered, for whatever reason, by their societal positioning.”

For more information please visit: www.flashofsplendour.com

Creative Future

// Tight Modern Submissions \\

50 works will be selected from submissions by marginalised or disabled artists to go on a touring exhibition across Sussex and London. The gallery is a minute replica of the Tate Modern, will dimensions of 8 ft x 5 ft with a 12 ft high chimney.

Images that are submitted should be original, photographs, collages or computer generated, measuring 18 x 13 cm or 13 x 13 cm. Each artwork entered will cost £5.

There are prizes of £250, £175 and £75.

DEADLINE: 4TH JUNE 2012

Once selections are made, the exhibition will take place at the following venues, on the following dates:

London: 13th – 17th June @ Royal Brompton Hospital

Brighton: 9th – 12th August @ East Street Bastion

London: 10th October @ Gillet Square, Hackney

Chichester: 9th – 11th November @ Pallant House Gallery

For more information please visit: www.wix.com/tightmodern/gallery

Studio Upstairs

RIGHT HERE RIGHT NOW @ CRE8 Centre, Hackney Wick

31st May – 7th June

“A group show focusing on the lives of ten Studio Upstairs artists…. Where the viewer is invited into the secret world of each artist.”

For more information please visit: www.studioupstairs.org.uk

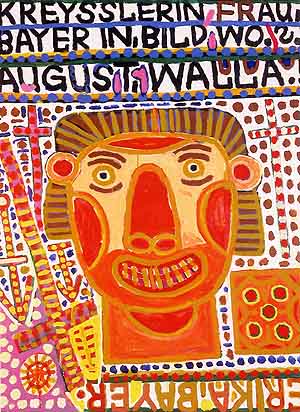

Outsider Folk Art Gallery

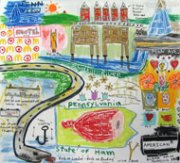

Intertwined @ The Freedman Gallery at Albright College – Reading PA, USA

20th May – 1st July 2012

This exhibition “examines the artistic relationship of a mother and daughter, and a father and son, who have experienced extraordinary circumstances.”

For more information please visit: www.outsiderfolkart.com

The Graeter Art Gallery

Tridacna @ The Graeter Art Gallery

Tridacna @ The Graeter Art Gallery

3rd May onwards

The artworks on display in this exhibition mirror the struggle of the Tridacna; a creature which when put in peril will vanish, leaving behind just a skeleton.

The exhibition includes pieces that represented “suspended dreams” and a “romantic merging of humanity, nature and animal.”

For more information please visit: www.graeterartgallery.com

Bethlem Heritage

Hollow Space and Outgrowth @ Bethlem Gallery

13th June – 13th July 2012

“Artists from Bethlem Gallery respond to the historical and art collection in the Archives and Museum.”

For more information please visit: www.bethlemheritage.co.uk