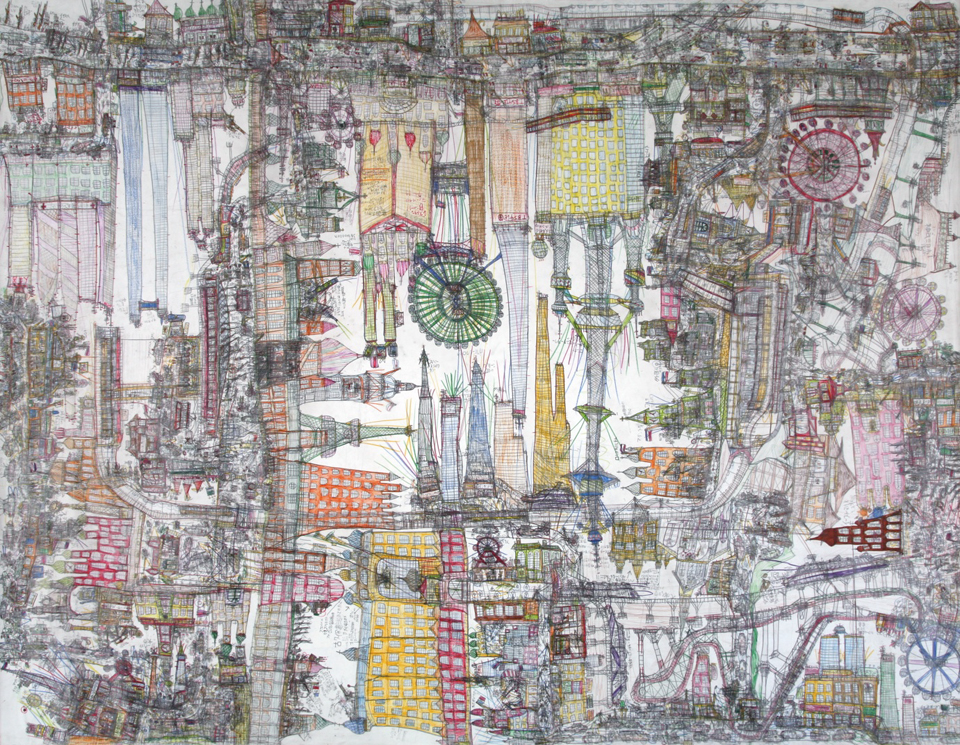

Above image: Marcel Storr

In Outsider Art under Analysis: Part One (Speakers), I wrote about the talk I attended at the Wellcome Collection on 15 June 2013. In this post, I will answer some of the questions raised during the discussion (no research, just my own thoughts). It would be great to hear everyone else’s answers too, so feel free to add a comment below the post.

1) Can ‘outsider artists’ talk about their work meaningfully and coherently?

This is a difficult one, as I know a lot of people like accompanying interpretative material to aid them when they view an artwork. However, I think that art is really another form of communication, and so the idea that some artists – for example those without speech or writing – can’t actually talk about their work seems quite unimportant. This is more of a question that encompasses the whole of art history and not just ‘outsider art’; do we need accompanying material, or is the work alone enough? I think a lot of artists who are aligned with/align themselves with the notion of ‘outsider art’ (and actually, artists more generally) do use creativity as a way of communicating their ideas, so for this reason, does it matter that some may not be able to ‘talk’ about their work?

2) Why do we feel we have to label people? Why can’t outsider artists just be called artists?

This is obviously an on-going debate with regards to the label ‘outsider art,’ which I have spoken about in a previous blog post. I, for one, would love for all art to be considered as just ‘art’ and all artists to be considered as just ‘artists.’ But I think it’s a bit more complicated than that. In the present day, I actually think that the term ‘outsider art’ is verging on redundant. In ten, maybe twenty years’ time, I don’t think we will use it. But, if having had a label at some point has helped raised awareness and can actually bring this art into the mainstream, then it can only be a good thing.

3) Did ‘outsider art’ exist before the 1930s?

The golden age of Outsider art was between 1880 and 1930 – so in short, yes! It emerged at this time because of the development and progression of European psychiatry. Patients were encouraged to draw, paint, and take part in alternative activities to aid their recovery. This was also the period when modern artists started to take notice of what was becoming quite a powerful and popular type of art. There was a lot of discontent due to accelerated mechanisation and urbanisation in Europe at this time, and of course, it encompassed two world wars and a period of huge unrest in between. Many artists working during this period were looking for new direction – they wanted a way to illustrate their discontent, a new way to depict the devastated world around them. The idea that ‘outsider artists’ were self-taught, yet representing the world as they saw it, and their inner worlds, regardless of whether this fitted with the accepted ‘canon’ of the time was something that really resonated– most notably with the German Expressionists such as Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Max Beckmann, and, of course, the Surrealists.

The term ‘outsider art’ itself was coined by Roger Cardinal in 1972, following on from Jean Dubuffet’s ‘Art Brut’ or ‘Raw Art’, which emerged in the 1940s.

4) What is ‘outsider art’? In simple terms – has it become outdated?

In simple terms, it is very outdated and almost redundant. The meaning of it has changed so much over the decades that actually describing it proves very difficult! It originated as a term to describe work created by those incarcerated within mental institutions, but has evolved to become more of an umbrella term for a whole host of different stylistic approaches – naïve art, folk art, self-taught art, to name but a few. Again, it is useful for the time being in that this art can be ‘called’ something, and is not just floating in the ethers, on the margins of the art world. In fact, particularly this year with the huge exhibitions taking place that are showcasing the talents of artists under this term, it seems almost ridiculous to describe this work as being ‘outside’ of the mainstream. The hope is that one day it won’t need a specific term and work created under this umbrella will simply be known as ‘art.’

5) Not everyone is an artist, and not everything is art. People have to go to art school and study what has come before to become an artist.

I really wasn’t sure about this statement. I know a lot of people work very hard to become artists in the dog-eat-dog art world; the go to art school, they learn about art and artists that have gone before, and they build on this in their own practice, BUT I do think that everyone has an inner artist, if this is too far, perhaps, then at least everyone has an immense amount of potential for creativity inside of them. I just don’t know who’s to say what is and isn’t art, and why people who aren’t formally trained cannot be considered as artists. I think this is one of the major reasons that the term itself needs to be forgotten; it gives the illusion of a distinction between who is ‘inside’ and who is ‘outside’ and therefore who can be called an ‘artist.’

6) Why is ‘outsider art’ not taught as part of the art historical canon?

This is something that I really hope will change soon. As part of my undergraduate degree, I was very lucky as I was actually taught about the emergence of outsider art, and about artists such as Louis Wain and Richard Dadd. I think people find it difficult to include in the canon because it is not a ‘movement’, and it did not take place over one definite period of time – it has been happening throughout this period – running parallel, if you will, alongside the history of modern art.

I also think that historians might find it difficult to talk about – there’s no definitive style etc. And, as Roger Cardinal said at the talk – it is a movement of individuals. I think the way forward is to include ‘outsider artists’ alongside teachings in the development of modern art. After all, they were immensely influential to hugely prolific modern artists, particularly those within the Surrealist movement, and this influence should not be forgotten.