‘Outsider art’ in the traditional sense – i.e. Jean Dubuffet’s description – alludes to an isolated artist, working on the periphery of the mainstream art world. Contrary to this controversial belief, many of the most notable ‘outsider artists’ of the twentieth century were supported, encouraged and ‘outed’ by some of the most famous ‘mainstream’ artists of the same century. This series of blog posts will highlight a few of these relationships, in the hope of rectifying the general thought that artists that often sit under the umbrella of ‘outsider art’ were completely immune to and separate from the twentieth century ‘mainstream’ art world. In fact, many of the ‘masters’ of modern art were hugely influenced by these relationships.

#1 Bill Traylor and Charles Shannon

#2 Alfred Wallis and Ben Nicholson

# 1: Bill Traylor and Charles Shannon

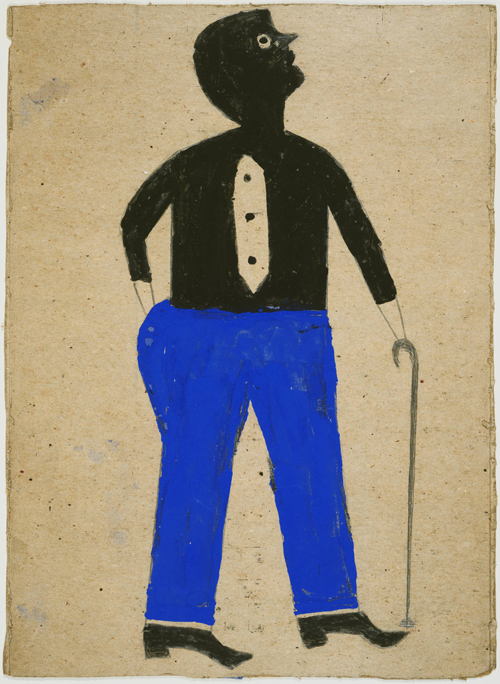

Born into slavery on a plantation in Alabama, Bill Traylor is perhaps one of the best known self-taught artists of the twentieth century. Working on the plantation he was born onto for many years of his life, Traylor moved to Montgomery in 1928 where he worked as a labourer until he became physically unable to continue. Only beginning to produce art when he was 85 years old, Traylor used mainly modest, everyday materials to create a unique portfolio of his experiences – both past and present. He recorded events from the everyday, of life in Montgomery, which he attempted to sell to passers-by on a sidewalk. It was on this sidewalk that a unique meeting would change the fate of his artistic career.

Charles Shannon – a painter and teacher – discovered Bill Traylor in 1939, as Traylor was perched on a box, drawing in the street near a fish market in his native Montgomery. Shannon supported the artist financially, and provided Traylor with materials as well as his first exhibiting opportunity at the New South Gallery in 1940. Despite full recognition of Traylor’s career as an artist not occurring until the 1980s (long after his death in 1947), Shannon is credited as having contributed significantly to the artist’s support network and therefore his later recognition.

Shannon was fascinated by the seemingly innate creativity that Traylor had discovered at such a late stage in his life, despite having never drawn or even been able to write beforehand. Shannon, in his article ‘Bill Traylor’s Triumph’, published in Art and Antiques in 1988, speaks of his experience of Traylor as an artist: “He worked all day; some evenings I would drop by around ten o’clock and he would still be there, his drawing board in his lap, a brush in his hand. He was calm and right with himself, beautiful to see.”[1]

Traylor was not known for talking about his work, but Shannon noted that he talked almost continuously whilst he worked – but, regretfully, he only recorded a very small number of these comments: “Now, I sometimes wish that I had [asked him questions]. I only knew what he volunteered to tell me.”[2]

After Traylor’s death in 1949, Shannon continued to be an advocate for his work despite the lack of public attention and interest. Many members of Traylor’s family in fact had no idea that he had been an artist, they were not aware of Shannon’s support of the artist, and they were not aware that it was Shannon who had saved his work. It wasn’t until 1979 that Shannon – in possession of 1200 – 1500 works by the self-taught artist – managed to secure an exhibition at the R. H. Oosterom Gallery in New York. Today, Traylor’s work is often considered as an important part of the development of twentieth century art – despite the Museum of Modern Art, NY, offering Shannon one dollar per piece in 1942; something the advocate was incensed by, returning the cheque and taking back possession of the works himself.

In 1986, when Michael Bonsteel asked Shannon what he thought made Traylor’s work great, he responded: “What made his work great is like trying to answer ‘what is grass?’ The rhythm, the interesting shapes, the composition, the endless inventiveness – it all reflects such a wonderful joy of living. His whole sense of life comes through. It was just the man. I think he was a great man. It’s not so much how he depicted or what he did. It was just the soul of the man.”[3]

‘Relationships’ series:

#1 Bill Traylor and Charles Shannon

#2 Alfred Wallis and Ben Nicholson

References:

[1] Charles Shannon, ‘Bill Traylor’s Triumph,’ in Art and Antiques, 1988, p 88.

[2] Mechal Sobel, Painting a Hidden Life: The Art of Bill Traylor, (Louisiana State University Press, 2009), p. 6

[3] Op. Cit., p 130

General References: