Recently, whilst undertaking some research around the role of the critic and what makes artists ‘successful’ in the art world, I came across a transcription of a lecture given by Sir Alan Bowness, Art Historian and Director of Tate (1980-1988), at the University of London in 1989. The talk centred on the idea of artistic achievement, and was titled The Conditions of Success: How the Modern Artist Rises to Fame.

In the text, Bowness outlines his idea that there are four steps that lead to an artist achieving recognition and success in the art world. What I found most interesting about this quite rigid ‘how-to’ guide is how little room for success it leaves for those who are not able to complete one of the steps. This, of course, ties into my interests around what continues to separate so-called outsider art from the cultural mainstream.

Early on in the lecture, Bowness asserts that “there is a clear and regular progression towards artistic success. There are,” he says, “in my view, conditions of success, which can be exactly described. And success is conditioned, in an almost deterministic way. Artistic fame is predictable.” These ‘conditions of success’ revolve around the idea of recognition. Recognition from whom, and when this occurs during the artist’s career.

The first condition is peer recognition, and Bowness quite boldly claims that this initial type of recognition is “at first a matter of personality as much as it is of achievement.” He goes on to speak about his discovery of David Hockney during the 1960 annual exhibition of the London Group (Hockney at that time being a 22 year old first year student at the Royal College of Art): “it was quite obvious to… a thirty year old art historian/critic like myself that here was an exceptional talent.”

My immediate issue with this condition is that it first requires the artist to already be rotating in artistic circles and communities. This is generally not the case for artists who are considered to be working outside of the mainstream. It is a condition that relies heavily on an artist having travelled the traditional route – art school, formal and informal networking, student exhibitions, etc. Some of the most well-known outsider artists (think Bill Traylor), did not start creating work until much later in life, and many lived or had lived lives on the outskirts of artistic communities and therefore outside of the possibility of any form of peer critique.

My second issue is that this also requires the artist to have a peer group that is already well established in the art world – or at least one that in some way already holds some kind of esteem. It relies on networks created at some of the most prestigious art schools in the world. Networks that include artists and creatives who already have some kind of influence or sway. This is something that not all aspiring artists are privy to. My final point on this condition is that not all of those we now see as ‘outsider artists’ (for want of a better phrase) originally saw themselves as artists or makers. How then, without even seeing themselves in this way, would they be able to integrate into these important artistic circles and achieve peer recognition?

The second condition that Bowness claims illustrates that someone is on the right path to success is recognition from those who write and talk about art. He notes that “the writer has two important functions: the first is to help create the verbal language that allows us to talk about art… The second… his contribution to the critical debate.” This condition comes, of course, with issues relating to the role of the critic, which I have written about at some length in previous posts. Who are these critics, and what gives them the power to recognise some people as artists, but not others?

The third condition for success is the recognition of patrons and collectors. Now, this where these conditions begin to become a little inextricable. They become tied to one another, and it becomes increasingly more tiresome to differentiate between the influence-r and the influence-d. Those who write about art (the critics, the curators), undoubtedly influence what sort of art prestigious collectors and patrons will buy and sponsor, and likewise, collectors and patrons with power and authority in the art world will have a hefty load of influence over which artists are celebrated by critics and exhibited by curators.

The final stage – the pinnacle – that artists must reach and ‘complete’ is that of being recognised by the public. This, Bowness claims, is what shows that an artist really has become ‘famous.’ To me, this is an interesting idea. From my previous posts – (one example here, and another here) – it seems almost to go without saying that the previous conditions for success will have a huge impact on whether an artist reaches this stage. Without some kind of celebration or support from critics, curators, or collectors and patrons, an artist will struggle to have their work seen by the public. And if the public can’t see the work, how can they possibly judge whether it is a success or not? It is apparent that an artist cannot skip a step on Bowness’ staircase to public acclaim and fame.

Bowness does talk about the psychological and socio-economic factors that can impede the artist’s journey to success. These factors, he ascertains, play a huge part in whether an artist really can make it to the top. For example, neither Van Gogh, whose mental health issues became a huge barrier, or Gauguin, who simply could not be in the right place at the right time, achieved acclaim or success in their lifetime. This says a lot about the journey for outsider artists – historical and contemporary – who in many different ways continue to come up against psychological or societal factors that will impede their success. What if they can’t afford – or simply aren’t able to – relocate to a big city where there is a vibrant artistic community? Does this mean that fame is just simply not within their reach?

Another of Bowness’ statements does not sit well in relation to the work of outsiders. He says that:

“The creative act is a unique and personal one, but it cannot exist in isolation. I do not believe that any great art has been produced in a non-competitive situation: on the contrary it is the fiercely competitive environment in which the young artist finds himself that drives him to excel.”

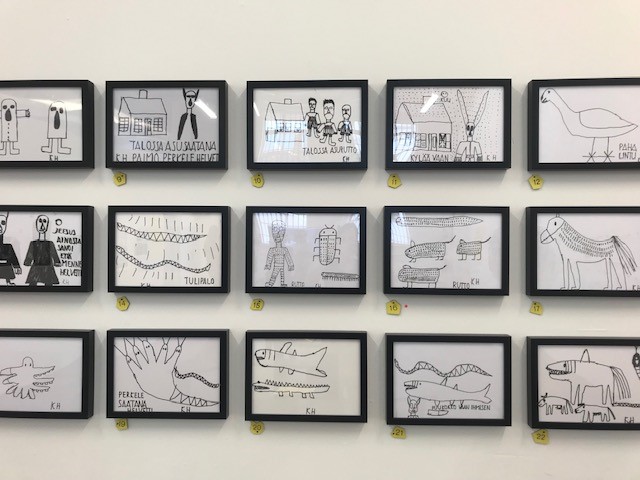

This, of course, raises many questions about the very nature of outsider art, much of which is created in isolation, and is not created as part of a competitive relationship with peers. I disagree wholeheartedly with this statement from Bowness. I think it relegates the act of making art – something so unique and innately human – to a formulaic, almost business-like endeavour.

But it is Bowness’ final statement in the text that I struggle with the most. He states that “to imagine that there are unrecognized geniuses working away in isolation somewhere, waiting to be discovered, is simply not credible. Great art doesn’t happen like that.”

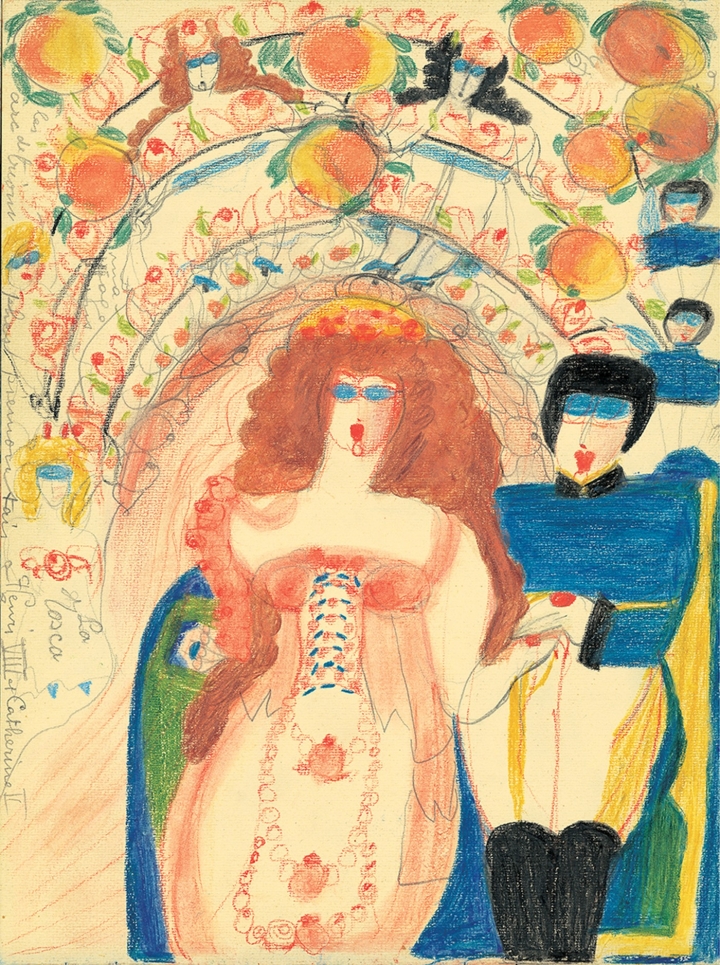

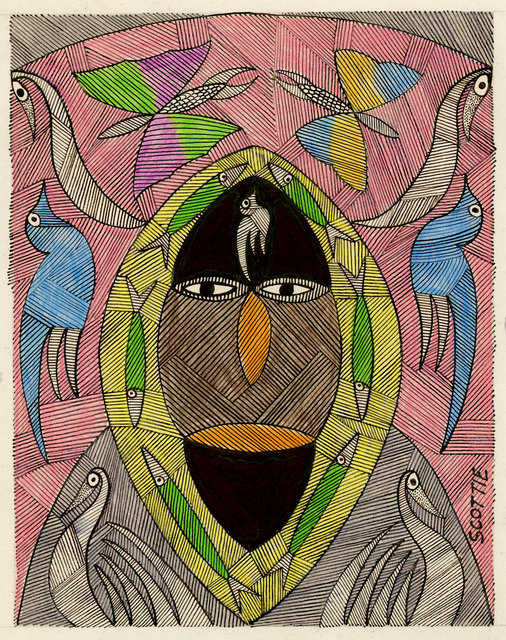

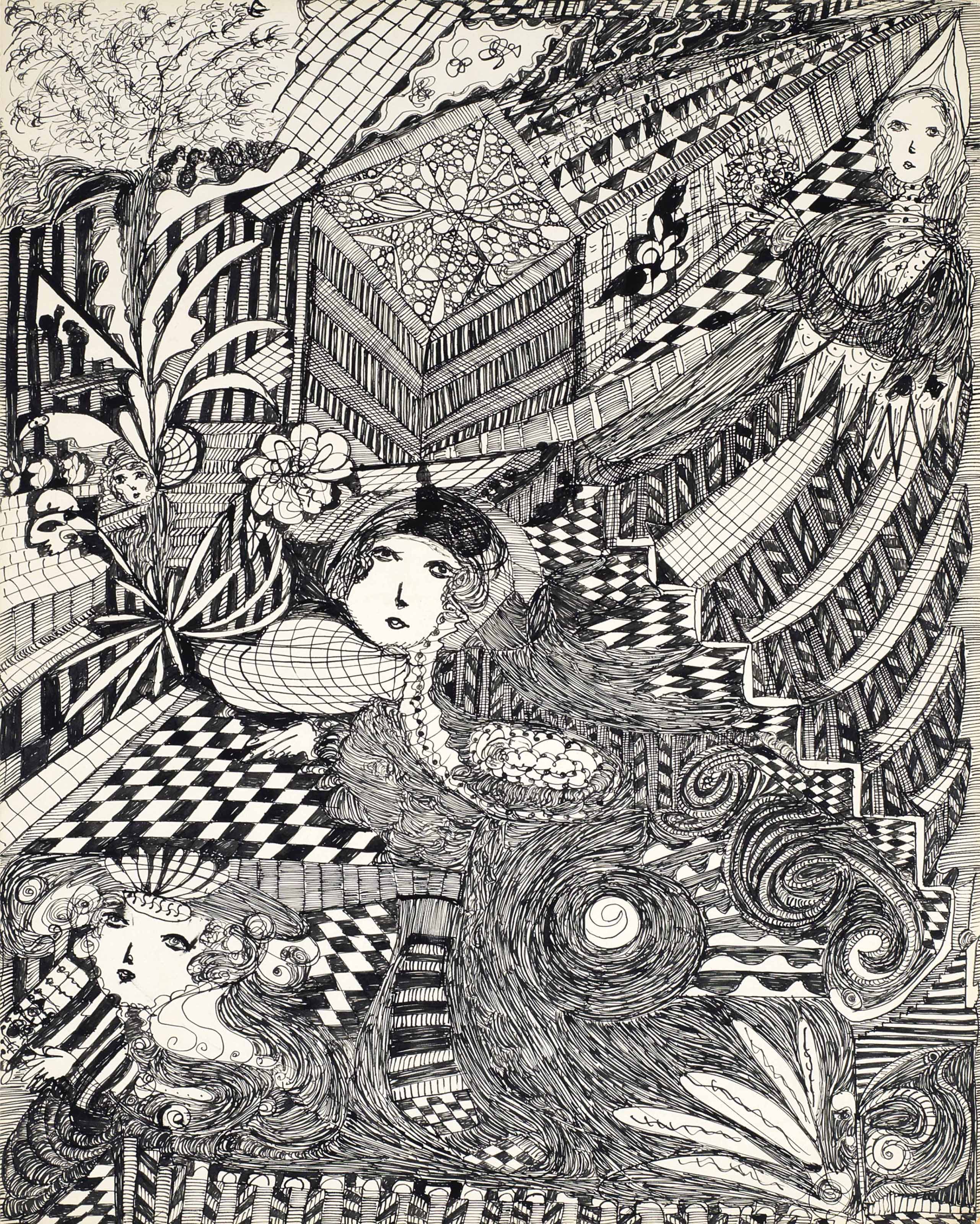

From my experience, this is exactly how great art happens. Perhaps the artist is not hidden away, hiding in isolation, but they simply have not been discovered yet. Maybe there are not even trying to be discovered. I think it is naïve to think that we all already know the greatest artists and the greatest art that has ever existed. To think that the best art is already publicly available – we already know where it is, who’s made it, where it’s being made, why it’s being made. I think this simply cannot be true. Think how many people are out there now, all over the world, making art – not for any specific audience, not for any specific purpose, but making, nonetheless. And to think that we cannot consider that to be ‘good’ or ‘successful’ art because it has not already been recognized (by peers, by critics, by collectors, and by the public), just seems to me incredibly absurd.

Bowness’ conditions of success once again outline the rigid, self-feeding system that epitomises large parts of the mainstream art world. Each condition depends on the previous, and all are working in each other’s best interests. This is just one of many examples highlighting how exclusive the art world is as a system. It leaves little room for success for those who are not already on the inside.