Apologies for such a break since the last blog post – 2022 is flying by! I’ve been continuing with my PhD research and over the last couple of months I have been interviewing artists who see themselves as facing some form of barrier to the UK mainstream art world. Although I have worked in this area now for over 10 years, I rarely get the chance to sit down one on one with artists and really listen to their story spoken in their own words, so this has felt like a real privilege. The interviews have been incredibly insightful, and I have been struck by how articulate artists have been about the inherent issues embedded within the UK’s cultural system.

(more…)Category: Art Theory

-

Changing the way we see success: is outsider art becoming the new mainstream?

Although it has not yet reached the highs achieved by auctions of ‘mainstream’ art, the monetary value of ‘outsider art’ is creeping up. This blog is written in light of the recent Christie’s auction of outsider art from the William Louis-Dreyfus Foundation which took place earlier this month.

(more…) -

Discovering Outsider Art: The Narrative of Otherness

Recently, I have been returning to the classic texts of outsider art in an attempt to uncover where the marginalisation of this type of work really began. My research has uncovered a few key areas that illustrate how ingrained the idea of ‘otherness’ and ‘us’ and ‘them’ is when it comes to outsider art and the artists who create it. This marginalisation and imbalance of power is so embedded in the culture of outsider art; in how it emerged, in how it is described, and in how it is valued, that it is difficult to move past its history and look towards a new, integrated outsider art that enjoys the same reverie as works that are readily welcomed into the cultural mainstream.

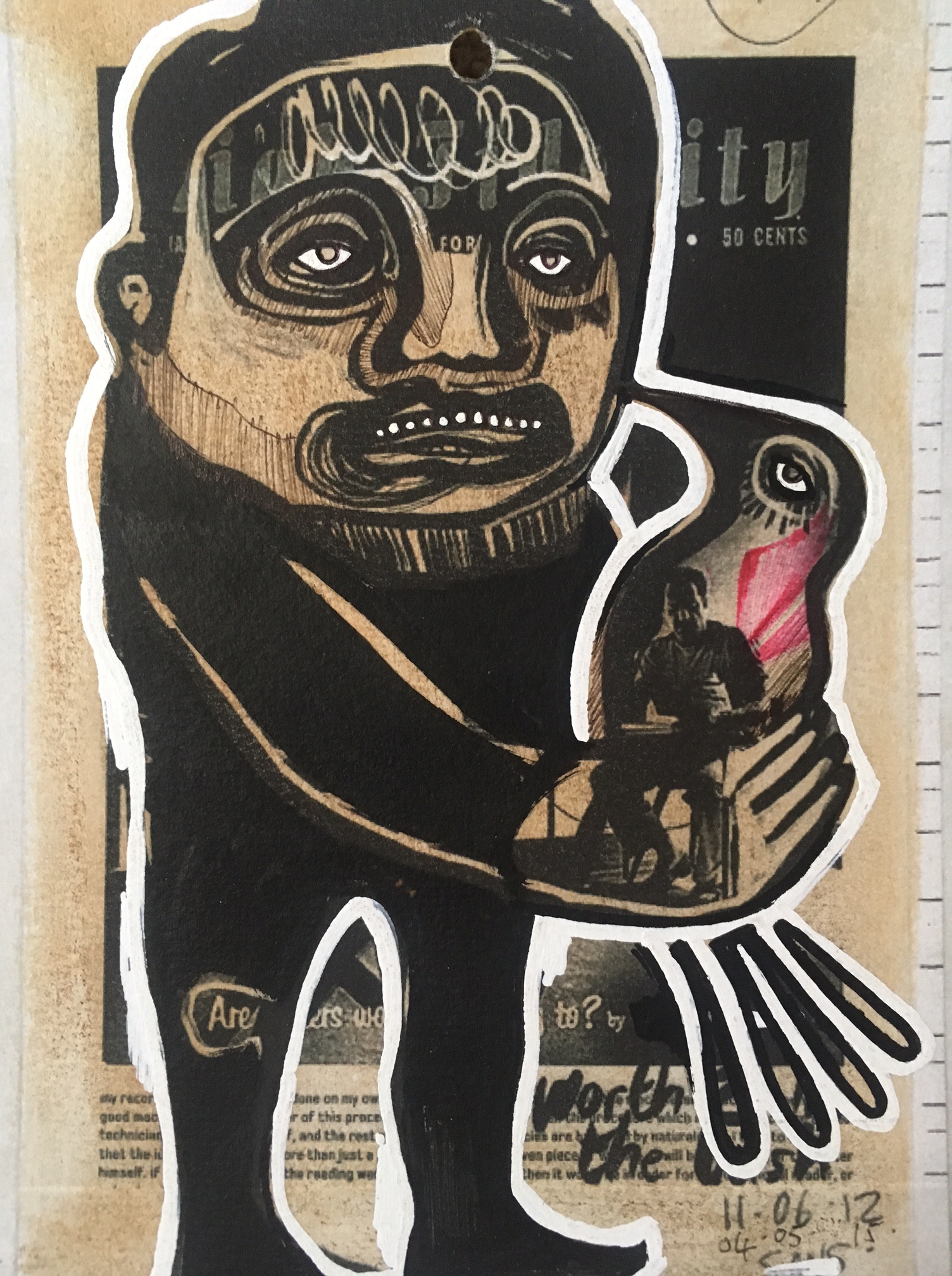

Drew Davies, Mr Roger My research has first led me to explore the emergence of outsider art. And here, already, we can see structural power imbalance at play. If we think back to the key developments in the emergence of outsider art, we see a pattern; outsider artists being ‘discovered’ by those already in positions of influence and power.

The first major – and most obvious – example is Jean Dubuffet and his coining of the term Art Brut. The story of Dubuffet and his support for Art Brut is an excellent illustration of how the system works. Dubuffet, for a start, was already an accepted part of the cultural mainstream. He was an artist in his own right; a disillusioned one, albeit, but accepted nonetheless. It was his position on the ‘inside’ that enabled him to throw caution to the wind and leave the mainstream for a world of raw and unfettered creativity. This example speaks to sociologist Howard Becker’s idea of the Maverick artist; an artist who has already achieved acclaim and acceptance within the mainstream who then goes it alone, creating more daring and outrageous work. Becker uses Duchamp as his key example, but Dubuffet equally fits the mould in his search for something different and other. The idea being that you have to already be on the inside to make real change – and to get noticed for it.

Jack Oliver, Ratfink Now Dubuffet’s name is inextricably linked with Art Brut and outsider art forever more. In his position as the creator of Art Brut, Dubuffet held – and still holds – all of the power. Often, it is not the artists whose names we recall when we talk about the category of outsider art, but Dubuffet’s name; he is now the father of this genre.

Like Dubuffet, there were other European artists who before the First World War were becoming disillusioned with the art world. They were dissatisfied with culture and society as a whole and were looking for something more authentic. It is these artists we see looking for inspiration in other communities, countries and continents – think Picasso and his intrigue with the primitive, or Kandinsky and his fascination with art made by children. It is similar to how the middle classes now seek authenticity in other cultures through travel. But still, it is a search for the other, a search for something different. This directly relates to a number of European artists becoming interested in the art of psychiatric patients following the publication of Hans Prinzhorn’s Artistry of the Mentally Ill in 1922. They were looking for something other, and they found it here, in the work of those who were removed both physically and socially from the worlds of these mainstream artists.

Cloud Parliament, I’d Like To Be Shod There is a history of this type of dissatisfaction amongst mainstream artists. But, almost always, their new and shocking work eventually becomes accepted as ‘progress’ and is welcomed into our historical canon – for example Surrealism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Cubism. This, however, has not been the same for outsider art. It has remained on the outside, a parallel running alongside the canon of the twentieth century mainstream.

Aside from artists already in acclaimed positions within the mainstream, we also have psychiatrists and medical professionals to thank for the emergence of the category of outsider art; particulary, of course, the work of psychiatric patients. I have mentioned Hans Prinzhorn already; psychiatrist, art historian and founder of the Prinzhorn Collection, but there are numerous others including Walter Morgenthaler, Dr Paul Gaston Meunier, Dr Charles Ladame. Whether we agree with the sharing of work by patients in psychiatric hospitals (with the issues of ethics and consent that come with it), what is at the core of this side of the emergence of outsider art is vulnerable artists being presented to the world by medical professionals. Again, people who already hold some kind of societal influence.

Robert Haggerty The third group that emerged during my research is arts professionals who hold some clout in the art world. Ultimately, it is curators, collectors, dealers and directors who shape the canon, and therefore the possibility of acclaim, celebration – and even just visibility – lies at their door. In his 2011 book ‘Groundwaters: a century of art by self-taught and outsider artists,’ Charles Russell tells the story of Alfred Barr, the first director of MoMA. Barr was in fact a great believer in the value of outsider and untrained art, organising a number of exhibitions that showed his support. His vision, however, was not matched by MoMA’s board of trustees, and Barr was consequently removed from the position of director. Although he remained employed in the collections department, MoMA has shown very little support for untrained art ever since. Here, we have the perfect example of how powerful people can change the course of history. Who knows what kind of art world we might be experiencing today if the work of untrained and outsider artists had garnered more support from MoMA’s trustees at the time.

So, even just the way outsider art has emerged as a field is made up of unequal power dynamics and issues of otherness. It is no wonder then, that there is difficulty in encouraging those inside the mainstream to see this work in the same light as trained artists. There is such a strong history of marginalisation here, right from the very beginning, and what is most apparent is that in this display of ‘us’ and ‘them,’ what we most desperately need are the voices of the outsider artists themselves.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts. You can post them in the comments below, or email kdoutsiderart@yahoo.com. Thanks for reading!

-

Outsider Art and the Art Critic

Over the past couple of months, I have been trawling through reviews of outsider art exhibitions published in the UK national press. It has been an interesting exercise, returning to some of the exhibitions I have visited over the past 10 years; this time, with my researcher’s head on. After diving into several of these reviews – most of which focused on the Wellcome Collection’s Souzou: Outsider Art From Japan, the Hayward Gallery’s Alternative Guide to the Universe and the Whitechapel’s Inner Worlds Outside, I started putting together a list of words and phrases that kept cropping up; words that actually seem a little out of place in a review of an art exhibition.

Lee Godie, Black Haired Woman, courtesy of ArtNet Mysterious, disturbing, criminal, eccentric, alienated, troubled, miserable, painful, tragic, psychosis, obsessive, chaotic, unhinged, imbecile, insane, lunatic, depressing, ranting, desperation, relentlessly garbled, utterly ridiculous, lost touch with reality.

The above are just a few of the words and phrases that jumped out at me. It’s not the most positive list, but this kind of sets the tone, as you can imagine, for what these exhibition reviews included. This emotive and, quite frankly, dramatic language is not uncommon when it comes to literature associated with outsider art exhibitions – whether that is in the press, in exhibition catalogues, or alongside the art in the exhibition space. This led me down a bit of a worm hole, thinking about the role of the art critic in representing outsider art to the wider public.

As I have mentioned before, we don’t teach our students about outsider art (in the UK, anyway) when they enroll on an art history course at any level, and usually, when a friend or family member asks what it is I’m researching and I answer with ‘outsider art,’ the majority of people look very puzzled. Actually, I was once asked if outsider art meant art that was created outdoors. But this puzzlement is understandable – the general public never hear about this work, and for the most part, many of even the most well-known outsider artists are only really known within the outsider art field. Because of this, we rely heavily on what we read about outsider art; from curators, from historians, and from critics. And because the work is, for the most part, pretty unknown, the language these curators, historians and critics use can be dramatic – or even voyeuristic to some extent. Human beings love hearing about the ‘weird and the wonderful,’ and they love hearing about people who aren’t like them (just think about the fascination a large part of society has with watching Netflix documentaries about serial killers). So this is what the critics play upon.

Martin Ramirez, courtesy of ArtNet When writing about outsider art, critics have an extra bonus in that the majority of (certainly the ‘traditional’) outsider artists did not consider their work to be ‘art’, and therefore did not write or talk much about it themselves. This means the critic is able to imbue their own views onto this work, and, particularly with the national newspapers, reach much wider art and non-art audiences. This kind of power and freedom (no fear of reprisal from the artists) is no doubt a factor in the overdramatising of this type of work. It is important to consider the role of the curator in this story too. Critics need some to pin their review on; something to ‘appraise against’; a theme or a narrative. Many exhibitions of outsider art are group shows lumping together anyone and everyone who might fit comfortably (or uncomfortably) under that spacious umbrella. So critics are left to review disparate works and people, finding common themes where they can; and this common theme is often health or disability.

The role of the critic in the wider art world is also paramount here. The art world is a market system, and there are people who run the system for their own or others’ gain. Critics are just a small cog in this wider network of sales, exhibitions, and fame. A small, but important cog. Critics are self-imposed definers of taste. They say what’s good and what’s not good, and, much of the time, their views will be plumped up by ulterior motives. I have mentioned Howard Becker and his sociological views about art in previous posts. He talks a lot about the theory of reputation, and how reputations (of artists, and of works), “develop through a process of consensus building in the relevant art world.” He also notes that “the theory of reputation says that reputations are based on works. But, in fact, the reputations of artists, works, and the rest result from the collective activity of art worlds.”[1]

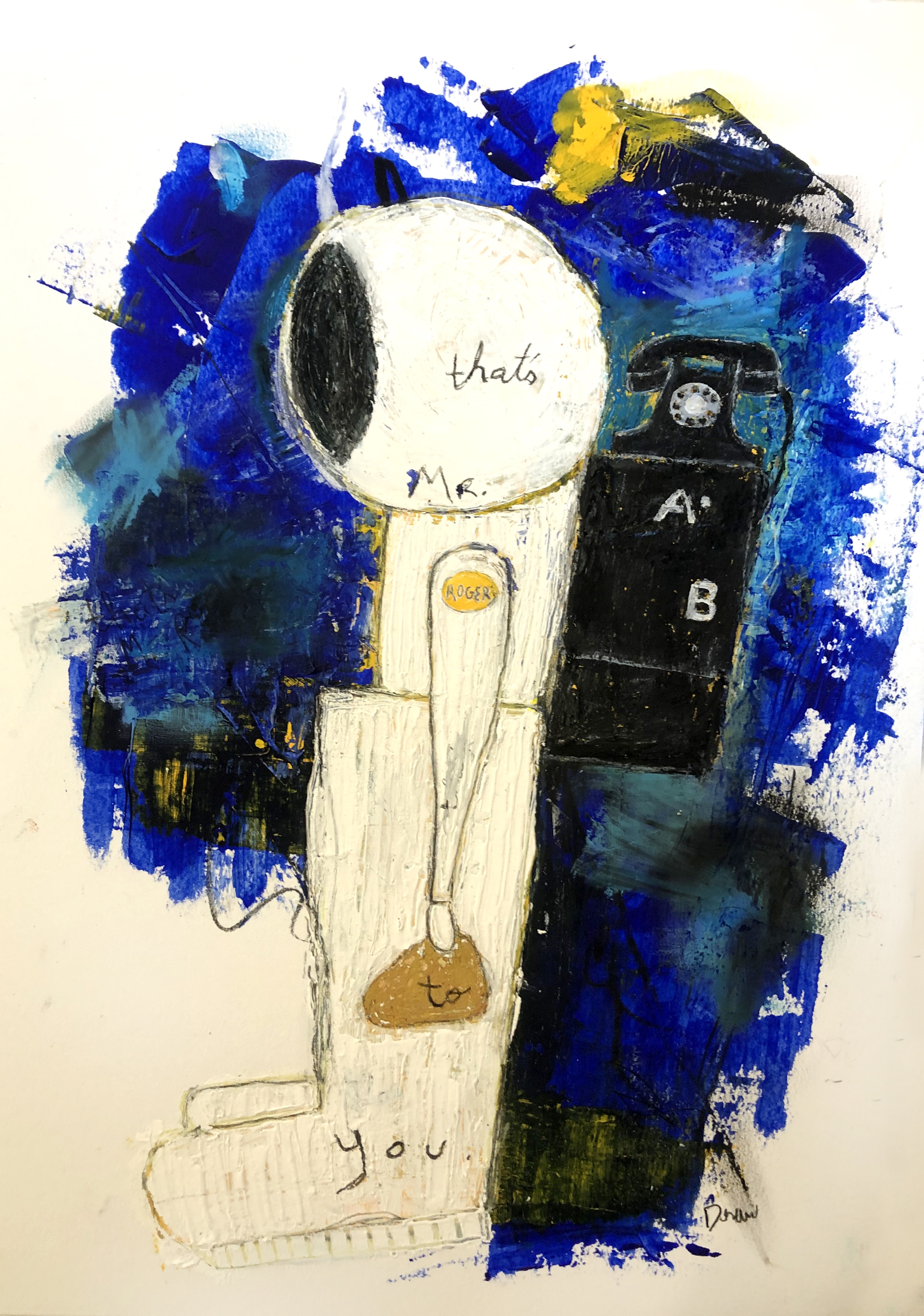

Marcel Storr, courtesy of Artforyum I found a nice quote by critic Laurence Alloway, which I’d like to finish with. He nicely summarises what he thinks the role of the critic should and shouldn’t involve:

“I think art criticism should be part of the communication system of a mass society, not elite-dominated, not reduced to a single tradition, and certainly not possessing any absolute value.” [2]

References

[1] Becker, Howard. S., Art Worlds, University of California Press, 2008

[2] Kalina, Richard, Imagining the Present: Context, Content and the Role of the Critic, Routledge, 2006

-

Three Ways Capitalism Impacts the Insider Art World

In this thought-piece, Jerry Fresia discusses how capitalism has impacted on the art world (inside and outside) over the past century.

Work by Jim Sanders

Power and the Capitalist Class: Capitalists don’t just sit off to the side minding their own business. Their business is the accumulation of capital (money and productive assets). They buy politicians, sit on the boards of museums and universities, and with major grantors, very high end gallerists, and an army of agents, they can shape and define what art fits into the insider art world of high end galleries, major art fairs, and auction houses. Central to the insider art system is the grooming of artists whose work supports their ideological needs, who are malleable, and, therefore, willing to accept direction into the inside circle.

The capitalist class first exercised its cultural power as a class when it defined, designed, and promoted a group of artists that articulated its ideological needs as an emerging hegemonic class following World War II. These soon-to-be-inside artists became known as the Abstract Expressionists. Using numerous capitalists back galleries and museums – primarily MOMA NYC which was created by the Rockefeller family – and the CIA (secretly directing the full range of art activities in western Europe as well as intellectual journals for 17 years), capitalists, during the post-war era, made it imperative that all artists pushed to the inside had to make work that was totally abstract, that is, “politically silent,” and free from any European influences. In other words, the American capitalist class, at that point in time, had enough power to create, in effect, a cultural factory. Out of this cultural factory, American Expressionism and the phenomenon of artists dependent upon capitalist cultural power, otherwise known as ‘inside artists’, were born.

Work by Manuel Bonifacio How Work is Produced: Capitalism is a specific way of making our houses, cars, computers, and even the way we grow our food. It is a system of production. Within this system, there are people designated as bosses: these are the people who work with their minds and do mental work. These people are the owners, sometimes referred to as planners. Not too long ago, they were called the bourgeoisie. And then there are the workers who in their work life are told what to do. They work with their hands and do mindless work. They are sometimes referred to as blue collar people, people who work on the line, or just plain workers. Not too long ago, they were called the proletariat. In the art world, they are called assistants.

All major artists, for a hundred years, prior to WWII were outsider artists. They controlled their own work in studios or out of doors and inveighed against the bourgeoisie regularly. They were consciously independent. No one told them what to do in their work. But by the 1960s, some artists began adopting capitalism a way of making their art. They called themselves “executive artists” or “ideas men” and turned their studios into factories, using other artists (assistants) as workers to make their art. Notable among these executive artists were Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist, Carl Andre, Robert Morris, Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons and others. Roy Lichtenstein predicted that all (inside) artists would eventually adopt factory values and practices in their work. These capitalist artists, working closely with capitalist financiers, marketing specialists, and luxury goods manufacturers were absorbed into the capitalist-class run museums-academy-auction-house troika. This is the core of what may be called the ‘inside.’

Work by Alan Doyle The Inside-Outside Artist Division: Work that is dependent on the approval of gallerists, financial backers, is produced for a particular market, or made in collaboration with luxury goods manufacturers, can be said to be instrumental, that is, produced as a means to satisfy some end external to the artist. This instrumental rationality is what defines the inside artist. His work (and it is mostly his) is always based upon a calculation: what must I do to please another and maximize market value? Every artist who works within this charmed inside circle is infected by this way of being and thinking. Wonder or mystery may not enter spontaneously into his process because his process is always a controlled activity of production. This uninviting situation is born of dependence and obedience that is central to the values of capitalist production.

At the moment that the inside artist is born, so too is the excluded ‘outside’ artist. Because she has not been directed into the inside circle, she is free from the need to make art that meets criteria external to herself. Independent and free, she is able to find passages into a realm where wonder is revitalized. She is free to give greater expression to play in her work as she feels the need. In other words, her work is authentically an expression of who she is. Her process is an activity of expression and of becoming.

Obviously, the outside artist needs the material rewards that accompany inside artist status so that she is able to sustain the liveliness of her work in comfort. But addressing the question of how the outside artist might go about achieving that end requires a further discussion of strategy. The point here, only, is to think in terms not of the art product, or genre or quality of the product of the outside artist vis-à-vis the product of the inside artist or of ways of penetrating the inside circle, but to think in terms of celebrating and protecting the process out of which the work of the outside artist has been given life. The inside-outsider separation is along that fault line.

By Jerry Fresia

http://www.fresia.com -

The Cycle of Cultural Consumption

First of all, I would like to start with an apology for the lack of posts of late. I do, however, have good news! I have recently started a PhD at the University of Chichester, in which I will be focusing on the relationship between outsider art and the mainstream art world. Specifically, it will be looking at whether, as is commonly suggested, there really has been a ‘rise’ in outsider art within the mainstream art world – with a particular focus on the last ten years or so.

My intention is to use this blog to share my thoughts along the way – and hopefully have some feedback from you, the reader. If you have any thoughts or comments on any of the posts featured on this blog, please contact me by emailing kdoutsiderart@yahoo.com.

Joanna Simpson, Good Luck Gum Nut Folk The first assignment that I have been working on as part of my PhD project has seen me entering the world of the sociology and philosophy of art. So, I have been reading a lot of Pierre Bourdieu! I find that blogging has been really helpful for me in amalgamating my thoughts and bringing them together in a less academically rigorous way. In light of this, I would like to share some of my thoughts so far about Bourdieu’s theories on art, and how I propose they relate directly to outsider art and outsider artists.

Pierre Bourdieu, a French scholar whose writings span the 1970s and 1980s, was a philosopher and self-proclaimed sociologist. Influenced by the works of his socialist predecessors; Ludwig Wittgenstein, Karl Marx, Max Weber, Bourdieu’s writings focus on the hierarchies of power that exist within the world. Most useful to me, of course, are his writings about culture. In these, he states that the way we consume and appraise culture is directly dependant on our class and educational background. So, people who have been brought up in households where trips to art exhibitions and excursions to the theatre are a regular – or normal – occurrence, are going to feel more comfortable consuming culture as adults. They will, Bourdieu asserts, already have the skills and tools available to them that will support them in deciphering the context and meaning of a work of art.

When reading Bourdieu, I was struck by what is apparent to many people working within (or with knowledge of) the art world. There seems to be an impregnable cycle within the art world that means that at every stage of participation, one needs to be from a certain social or educational background. I will call this cycle the ‘cycle of cultural consumption.’ To write about this cycle, I will begin with the artist. However, it is important to note that the artist is not the beginning of the cycle – the artist is just a part of it; the artist could in theory be the beginning, the middle or the end (see diagram above. I hope this will become clearer as I explain each cycle component.

Bourdieu does not write a lot about why artists create. But he does write about who or what influences an artist and how this has changed over the course of the previous few centuries. Prior to the nineteenth century, many artists were commissioned directly by the Church or the State, meaning they had little to no control over the content of their work. The Church and the State held all of the power. However, with the turn of the twentieth century – a century that in its youth in Europe was marred by uncertainty, instability, discontent, and of course, war – a revolution was starting. Artists were becoming autonomous individuals who were inspired by the context within which they were living and working.

Artwork by Jim Sanders So it seems that at this point the artist was beginning to take back some power. But hold on! How were these artists able to do this? How were they able to erase centuries of codes and language commonly used within works of art – and used, too, by educated cultural consumers who could fluently understand these codes and this language. Because, Bourdieu says, artists like Edouard Manet and Marcel Duchamp were already inside the art world. They were only able to challenge the accepted norm in such a spectacular way because they were already big fish swimming in the ocean of the art world. So, not so revolutionary when we look at it like this.

To relate this to outsider art; it seems it is possible for artists creating challenging, unusual, unique work to have an impact on the art world – to have this work shown and to have it seen. But only if the artist is already able to navigate the art world, which generally assumes that a person has taken the ‘preferred’ educational route (art school), which is generally only possible for people from a certain educational background (most commonly middle-class or upper-class).

The next players in my cycle theory are the ‘taste-makers.’ These are the people who decide what work is shown in a museum or gallery, and therefore what we (the public) consider to be art. These are the curators, the critics, the gallery and museum directors. The gatekeepers. We know these gatekeepers exist as tastemakers because art is such a subjective topic that if there weren’t people in these positions of power making decisions about what we see before we even know what the options are, then there would certainly be many more ‘famous’ or ‘admired’ artists in the world. Imagine for a moment the vast amount of work being produced by artists every single day. All over the world, every minute, every hour. In a world of seven billion people, there is going to be at least one person who likes each new creation. But then why isn’t this reflected in what we see in museums and galleries. Why do we see the same ‘big’ names, the same ‘big blockbuster’ shows? The same artists who are the ‘flavour of the moment’? We see these precisely because of the existence of the taste-makers and gatekeepers who are making our decisions about cultural and aesthetic value for us.

Artwork by Alan Doyle And the decisions of the tastemakers and gatekeepers favour artists from a specific background (social and educational) because they too are from these backgrounds. In 2015, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport highlighted that 91.8% of jobs in the creative economy in the UK were done by people in ‘more advantaged socio-economic groups’ compared to 66% of the jobs market as a whole.[2] Being from these backgrounds means that tastemakers and gatekeepers curate and interpret works by people from a similar background to themselves (who they relate to – makes sense right?), and therefore for people from a similar background. Again, to bring this back to outsider art – is a curator going to choose to exhibit work by someone who potentially attended the same art school as them, is their peer in that sense, or work by someone who is from a background that they really have no experience of and are therefore unable to relate to?

The Museum Association’s 2015-16 report Valuing Diversity: The Case for Inclusive Museums noted that “museum collections are often not interpreted from diverse viewpoints… Often the good work that comes out of projects is not used or displayed in the long term and therefore is inaccessible to people who would be interested in engaging with narratives that are relevant to their experience.”[3] This quote brings me onto the third person in our cycle of cultural consumption – the consumer.

The artist makes the work, it is then chosen (or not chosen) by the tastemakers and gatekeepers. If it is chosen, maybe it is exhibited with some accompanying wall labels. Maybe these wall labels are written in a language that is unintelligible to someone who has no prior experience of the art world or art school. Someone from a low socio-economic background, or someone who didn’t attend university might visit this exhibition. Whilst there, they realise they are unable to relate to the work that has been produced, because it has been produced by someone from a certain social and educational background that is a world apart from their own experiences. They are unable to understand the codes used within the interpretative material because, again, it has been chosen and written by someone who is from a very different social and educational background. After an experience like this, would you think that the cultural world was for you? I know that I certainly wouldn’t.

Artwork by Jim Sanders Much of Bourdieu’s writing is informed by experiments and studies he conducted, in particular focusing on understanding the cultural consumer. In The Love of Art, a study conducted by Bourdieu in French museums found that 55% of visitors to French museums held at least a Baccalaureate. Only one per cent of visits were made by farmers or farm labourers, and 4% by industrial manual workers. Tellingly, 23% of visits were made by clerical staff and junior executives, and 45% made by people from an upper class background.[3] Although conducted around 30 years ago (and in France), these results are reflected in data collected much more recently by Arts Council England for their 2017-18 Equality, Diversity and the Creative Case report. The report highlighted that the most frequent National Portfolio Organisation attendees were supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, administrative and professional workers, making up 28.9% of visitors. At 10% of all visits, the least reflected group was semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers.

So here completes the cycle (well, not completes, but continues). When you look at it like this – as Bourdieu does, it becomes clear why efforts need to be made to diversify our arts workforce, our arts audiences and, of course, the art we show in museums and galleries. If we make an effort to diversify just one segment of this cycle of cultural consumption, the ripple effect will surely create a more reflective, innovate and exciting art world that everyone (from all social and educational backgrounds) can enjoy and participate in.

By Kate Davey

References

[1] Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Creative Industries: Focus on Employment, 2016, P6

[2] Museums Association, Valuing Diversity: The Case for Inclusive Museums, 2015-16, P 14

[3] Bourdieu, Pierre and Alain Darbel, The Love of Art, Polity Press, 1991, P 14

Useful books/articles on or by Pierre Bourdieu

Richard Jenkins, Pierre Bourdieu, Routledge, 1992

Pierre Bourdieu, ‘Intellectual Field and Creative Project,’ in M. F. D Young (ed.), Knowledge and Control: New Directions in the Sociology of Education, Collier-Macmillan, 1971

Karl Maton, ‘Habitus,’ in Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts edited by Michael Grenfell, Acumen, 2008

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Routledge and Kegan, 1979

Pierre Bourdieu and Alain Darbel, The Love of Art, Polity Press, 1991

Feature image by Alan Doyle

-

The Autodidact: What Does it Take to Make it Big?

I can only apologise for the lack of posts in recent weeks – I hit the ground running at the start of 2018, and haven’t managed to stop just yet. However, I wanted to write a quick post for you as a couple of days ago, I was doing my usual crawl through the internet for the latest news on outsider art: upcoming exhibitions, auctions, in depth articles on individual artists, when I noticed the recurrence of a new word alluding to artists creating outside of the cultural mainstream. The word was ‘autodidact’, which literally means ‘a self-taught person.’

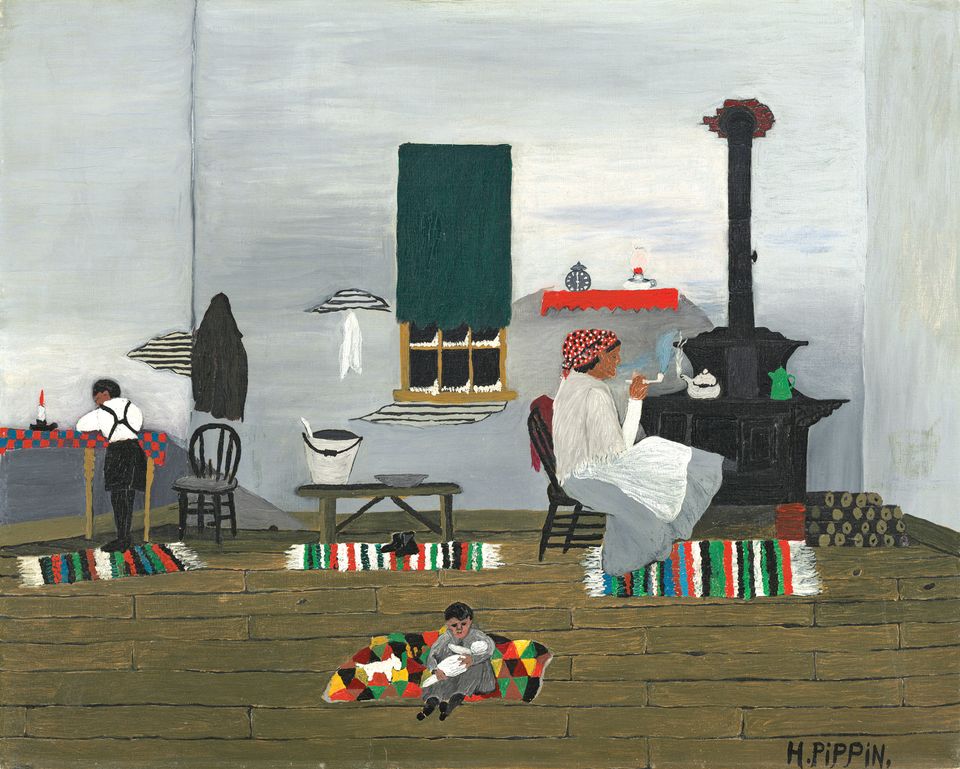

Interior (1944) by Horace Pippin (c) National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC The first occurrence of the word appeared when I was reading an article on the new ‘Outliers and American Vanguard Art’ exhibition opening at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. The exhibition, the article notes, aims to “reconsider the ubiquitous but limited ‘Outsider’ designation as an umbrella term for autodidact artists.” Also interesting is the title of the exhibition itself – more specifically, the use of the term ‘Vanguard’ which means ‘a group of people leading the way in new developments or ideas.’ Both terms are new (to me, anyway), when it comes to describing the work of those traditionally known as outsider artists.

Aloïse Corbaz, image from “Brevario Grimani (circa 1943), 19 pages, bound, in a notebook, colored pencil and pencil on paper, 9 5/8 x 13 inches, collection abcd/Bruno Decharme (photo courtesy of Collection abcd) The second occurrence of the term (that I came across within the space of about half an hour!) was in an Hyperallergic article about the American Folk Art Museum’s new show, ‘Vestiges and Verse: Notes from the Newfangled Epic.’ In this article, author Edward Gomez notes that the exhibition, “organized by Valerie Rousseau, AFAM’s curator of self-taught art and at brut… calls attention to the integration of text and image in works made by a diverse group of autodidacts.”

The most notable thing about the use of the term – following my reading of the articles and after a quick Google search – seems to be the predominantly positive slant the term gives to art work that is so often seen as ‘lesser’ or ‘not the norm.’ There is a whole Wikipedia page of celebrated famous autodidacts, including but not limited to authors Terry Pratchett and Ernest Hemingway, artists Frida Kahlo and Jean Michel Basquiat, and musicians David Bowie, Jimi Hendrix and Kurt Cobain.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkeys (http://heard.org/exhibits/frida-kahlo-diego-rivera/) I didn’t, however, see any renowned ‘outsider’ artists on the list. There still seems to be some sort of invisible barrier that separates these big stars of the arts and ‘outsider’ artists – despite there often being similarities in their backgrounds and circumstances. For example, although Basquiat’s background and style of work could undoubtedly be classed as ‘outsider’ (he ran away from home at 15, dropped out of school), he seems to have broken into the mainstream art world without too much trouble. In fact, he was the focus of a very popular exhibition at the Barbican that closed this month.

Jean Michel Basquiat (https://www.artsy.net/artist/jean-michel-basquiat) So, my question (as ever), is what creates this gulf between artists who gain fame and fortune through their work, and those whose legacies are confined to the barracks of ‘outsider’ art? What makes someone eligible to be included in Wikipedia’s ‘autodidact’ list? Do they have to be a certain kind of self-taught? I’d be interested to know your thoughts, so feel free to leave any comments below.

-

Aboriginal art, outsider art, and a code of conduct

In this post, writer Nick Moss considers the benefits of having a ‘code of practice’ for galleries and museums when working with outsider artists – much like there is a code of practice for those working with Aboriginal artists.

“It is perhaps to do a disservice to both art forms to make too much of comparisons between Aboriginal art and art produced by self-trained artists and artists in institutions. However, it is true of both that ab initio they were not produced for the commercial art market, and were produced by artists who had no experience of the snares and ruses of that market or the peculiarity and irrationality of its attributions of value.

Aboriginal art is rooted in the telling of the ‘Dreamtime’ stories – the symbolic telling of the creation of the world. The ‘Dreamtime’ stories are reckoned to be over 50,000 years old, and have been handed down through generations over time. They are expressed in the complex symbolic language of the Aboriginal peoples and captured in a traditional iconography which combines with stories, dance and song to pass on ‘Dreamings’ and so preserve the rites and maintain the development of Aboriginal culture in the face of settler opposition and state violence. However beautiful the works may be, their visual language is intended to serve a communicative and history-embodying rather than primarily aesthetic purpose. The works that now are produced on canvas, were, until the development of a commercial market for them, more usually produced by painting on leaves, wood carving, rock carving, sculpting, ceremonial clothing and sand painting.

In this sense then, the comparison with ‘outsider art’ can be made – outsider art often expresses private mythologies which are communicated through complex, self-produced symbolic languages, and can be set down in a variety of media, often determined by the extent to which the artist has access to particular materials at hand.

Aboriginal art serves a primarily communal function. Its attraction for, and appearance within, the commercial art market is a secondary feature of the fact of its production. This is both its strength and its weakness. Again, the comparison to outsider art can be made.

As the artist Wenten Rubuntia put it in The Weekend Australian Magazine, April 2002

‘Doesn’t matter what sort of painting we do in this country, it still belongs to the people, all the people. This is worship, work, culture. It’s all Dreaming.’

As commercial art dealers and galleries made inroads into Aboriginal communities in the 1970s, they began to take advantage of the artists who had no experience of the commercial art world, its contractual or valuation norms, and in any event were not making art for the business of art – some artists recognised the need for self organisation.

As an example, artists at Papunya and Alice Springs observed first hand the development of the private art market and the exploitation of their friends and thus formed the Warlukurlangu arts centre. The name ‘Warlukurlangu’ derives from an important Jukurrpa (Dreaming) and means ‘belonging to fire.’ The name was chosen by a number of older men and women who saw the need for an art centre and endeavoured to form an organisation that represented their interests as artists but also recognised and determined to defend the importance of the cultural laws which are embodied in the stories depicted in paint. The establishment of Warlukurlangu was one way of ensuring the artists had some control over the purchase and distribution of their paintings.

As the market for Aboriginal art increased both with regard to the volume of works coming to market and the venality of that market, the Australian Senate initiated an inquiry into issues in the sector. It heard from the Northern Territory Art Minister, Marion Scrymgour, that Aboriginal artists were often tricked by backpackers into selling their art on the cheap, and that backpackers were often the creators of purportedly Aboriginal art being sold in tourist shops around Australia:

‘The material they call Aboriginal art is almost exclusively the work of fakers, forgers and fraudsters. Their work hides behind false descriptions and dubious designs. The overwhelming majority of the ones you see in shops throughout the country, not to mention Darling, are fakes, pure and simple. There is some anecdotal evidence here in Darwin at least, they have been painted by backpackers working on industrial scale wood production.’

The inquiry’s final report (Standing Committee on Environment, Communications, Information Technology and the Arts: Indigenous Art – Securing the Future of Australia’s Indigenous Visual Arts and Craft Sector) made recommendations for changed funding and governance of the sector, including a code of practice. The report itself is a classic fudge, a refusal to fully address the ethical and legal issues arising from the commercialisation of Aboriginal art. Thus:

‘There is no doubt that there have been unethical, and at times illegal, practices engaged in within the field of Indigenous arts and craft. There are probably still instances of these problems, and there may be people seeking to take advantage of issues within the sector by ripping off artists or art centres.’

Nevertheless:

‘In spite of all this, the committee urges everyone in the sector to recognise each other’s sense of commitment, and reap the benefits of co-operation, rather than sow seeds of rancour and division.’

The Committee refused to take a stance explicitly in support of the formal regulation of the art market in relation to its exploitation of Aboriginal art. In effect, it concluded that even bad business was good business, in that it allowed Aboriginal artists to benefit from the untrammelled joys of free market capitalism.

‘Much of what was claimed about business practices appeared to be based on hearsay, and there was little tolerance of the diversity of people and legitimate ways of doing business which might all contribute to the benefit of Indigenous creativity, Indigenous art and Indigenous prosperity.’

The ultimate outcome – self-regulation via a Code of Practice was far from ideal, but the Code of Practice itself makes for useful reading. In particular, the section on Dealing with Artists, which is produced below in full:

Dealer Members must use their best endeavours to ensure that every dealing with an Artist in relation to Artwork involves the informed consent of the Artist. The following clauses will assist Dealer Members to ensure they have the informed consent of Artists.

3.1 Provide a Clear Explanation of the Agreement: Before making an Agreement with an Artist in relation to Artwork, a Dealer Member must clearly explain to the Artist the key terms of the proposed Agreement, so that the Artist understands the Agreement (for example, using a translator if required). The explanation should be given by the Dealer Member to the Artist either directly, or through an Artist’s Representative, in the manner requested by the Artist or Artist’s Representative. If there is any doubt about whether the Artist fully understands the explanation, the Dealer Member must also give the Artist the opportunity to ask a third party for assistance to help the Artist to understand, and negotiate changes to, the proposed Agreement.

3.2 Agreements with Artists: An Agreement between a Dealer Member and an Artist in relation to Artwork (whether written or verbal) must cover the following key terms: (a) a description of the relevant Artwork(s), including the quantity and nature of the Artwork(s); (b) any limitation on the Artist’s freedom to deal with other Dealers or representatives; (c) whether the Dealer Member is acting as an Agent or in some other capacity; (d) the cooling-off rights (which must be in accordance with clause 3.3) and how the Agreement can otherwise be changed or terminated; (e) costs and payment terms for the Artwork (which must be in accordance with clause 3.4); (f) details about any exhibition in which the Artwork is to appear, and any associated promotional activities; and (g) any other information determined by the Directors and notified to signatories to the Code from time to time.

3.3 Artist’s Cooling-off Rights (a) An Artist or Artist’s Representative may terminate an Agreement within: (i) 7 days after entering into the Agreement; or (ii) such longer period as is agreed between the parties. (b) A Dealer must not require the Artist to pay any fees, charges, penalties, compensation or other costs as a result of the Artist exercising cooling-off rights under this clause 3.3.

3.4 Payment for Artists: An Agreement must also cover the following in relation to each Artwork: (a) the amount of the payment and the means by which the payment will be made; (b) the date by which payment to the Artist will be made which (unless otherwise agreed) must be: (i) where the Dealer Member is acting as an Agent, no later than 30 days after receiving funds for the Artwork; and (ii) where the Dealer Member buys Artwork directly from the Artist, no later than 30 days after the Dealer Member takes possession of the Artwork; (c) if the Dealer Member is acting as an Agent, the amount of the Dealer Member’s commission; (d) any factors known to the Dealer Member that could affect the payment terms; and (e) the cost of any goods and services (e.g. canvas, paint, paintbrushes, framing, etc) to be deducted from the payment to the Artist (if any).

4.1 Record Keeping by Dealer Members (a) A Dealer Member must keep records of all dealings with Artists, providing clear evidence of the key terms, and performance of those key terms, of any Agreement between the Dealer Member and Artist (the Records). (b) If the Dealer Member is an Agent, the Dealer Member’s Records should also include: (i) details of Artwork held by the Dealer Member for sale; (ii) the dates of sale of Artwork by the Dealer Member; and (iii) the type and quantity of Artwork sold by the Dealer Member and: (A) the price received by the Dealer Member for the Artwork sold; and (B) details of the payment to the Artist (including the amount, date and method of payment) and details of each amount deducted by the Dealer Member from the sale price of the Artwork (for example, the Dealer Member’s commission on the sale). (c) If the Dealer Member purchases Artwork and subsequently on-sells the Artwork, the Dealer Member’s Records should also record the price the Dealer Member was paid for the sale of that Artwork.

4.2 Request for Dealer Member’s Records: A Dealer Member must provide a copy of the Dealer Member’s Records that relate to an Artist or Artwork to the Artist within 7 days of a request by the Artist (either directly or through an Artist’s Representative), provided that the Dealer Member is not obliged to make the same Records available to an Artist more than once every 30 days. The Dealer Member must provide a copy of the Dealer Member’s Records to the Company, in response to a request in writing by the Company.

The purpose of this article is to put forward a (relatively) simple proposition. If we can accept that there is a similarity in form and content between Aboriginal art and outsider art (both use complex symbolic forms and mythologies to tell stories through works which are not primarily produced for the art market, and both are produced by artists who (because of their socio-economic situation/confinement/lack of knowledge of commercial practice) are vulnerable to exploitation by the commercial art market, then we ought equally to be able to accept that there is a need for the adoption of a similar Code of Practice to protect the interests of outsider artists. The proposition therefore is this; all gallerists and dealers in outsider art should voluntarily adopt and display the excerpt from the Code of Practice above, as a statement of a commitment to dealing ethically with outsider artists, and all art workers, art therapists, agents and educators should make sure the artists with who they work are made aware of the relevant sections of the Code and educated in its rights, its implications and benefits for them.”

‘Innocence is a splendid thing, only it has the misfortune not to keep very well and to be easily misled.’

― Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of MoralsBy Nick Moss

**All images have been sourced from image-sharing websites

-

The ‘Savant’ Artist

I have wanted to write about this subject for a while now, ever since I first received a wall calendar of a certain artist’s work as a Christmas present over two years ago. Since then, I have been lucky enough to see this artist’s work in person at the Paris Outsider Art Fair in 2015, and have now purchased another calendar, four notepads and a book. The artist is Gregory Blackstock, a ‘savant’ with a gift for drawing.

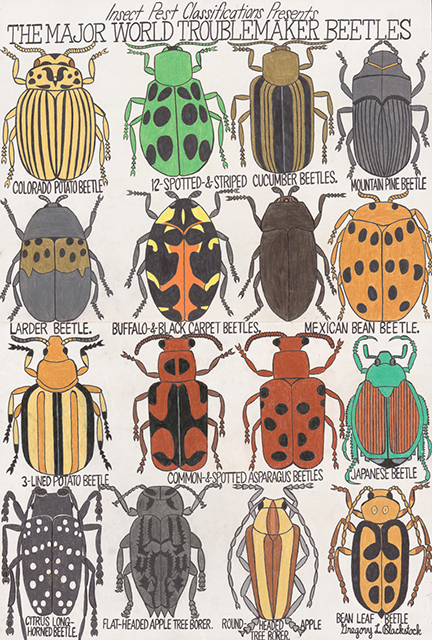

Gregory Blackstock, The Major World Troublemaker Beetles, Image courtesy of Raw Vision This post will focus on the phenomenon that is the ‘savant’ artist. The term savant is most commonly used to describe someone with a developmental disability (for example autism) who demonstrates extraordinary abilities. Savants like Blackstock have long been considered within the outsider art bracket, and have been represented in various exhibitions on the subject, including the Hayward Gallery’s ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe’ in 2013.

The most famous savant outside of the art world is likely to be Kim Peek, who inspired the film Rain Man, which in turn raised awareness of ‘autistic savants’ – or people with extraordinary abilities. Peek’s extensive knowledge library included world and American history, people and leaders, geography, sport, movies, the Bible, calendar calculations, telephone area codes and Shakespeare. Although there are many savants who do not express their abilities creatively, there are a huge number who do. The Wisconsin Medical Society dedicates a whole page to Artistic Autistic Savants, noting that “to many of the artistic savants, it is their release – their escape – their way to fit into a noisy and disordered world. Their way to connect with the people around them. They create and they perform because they are compelled to by the forces that make them unique, but they also do so because it brings them tremendous joy.”[1]

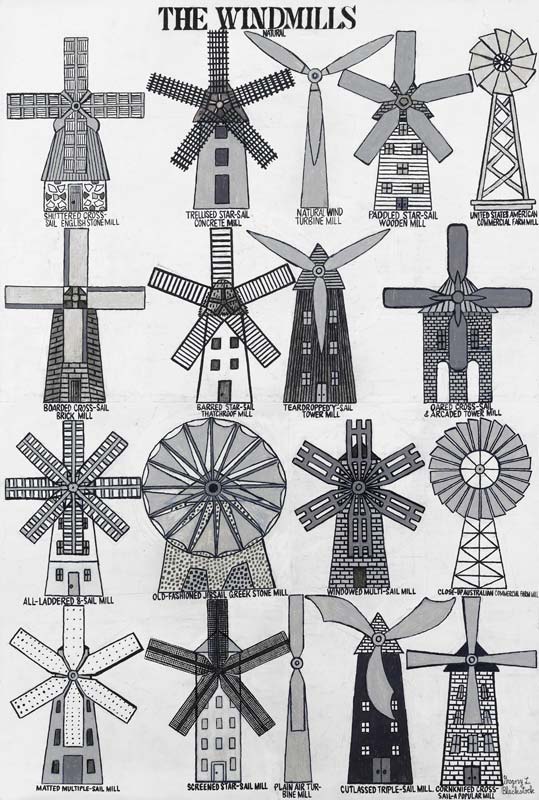

Gregory Blackstock, The Windmills, Image courtesy of the Greg Kucera Gallery In this post, I want to outline the work of four ‘Artistic Autistic Savants’; Gregory Blackstock (b. 1946), George Widener (b. 1962), James Henry Pullen (1835 – 1916), and Esther Brokaw (b. 1960). The work of all four is exceptional in its accuracy, whether that be in the representation of historical facts and dates, lists of obscure animals, hand-carved ships, or the leaves of a tree.

Esther Brokaw, Wildflowers, Image courtesy of Artslant In his book ‘Outsider Art and the Autistic Creator’, Roger Cardinal writes about Blackstock’s outstanding ability to regurgitate thousands of facts, images, numbers, and languages from memory – he can even recite the names of all of the children from his schooldays.[2]

Darold A. Treffert, in his foreword for ‘Blackstock’s Collections’, writes that “Blackstock shows those characteristic traits that constitute Savant Syndrome: an extraordinary skill coupled with outstanding memory grafted onto some underlying disability. But while all savants have that basic matrix, each savant is also unique, and that certainly is the case with Blackstock. First of all, his meticulously drawn lists of all sorts of items are , as an artistic format, inimitable. Second, most savants have skills in only one area of expertise, such as art, music, or mathematics – spectacular as those skills might be. But Blackstock has several areas of special skills, a somewhat unusual circumstance among savants.”[3]

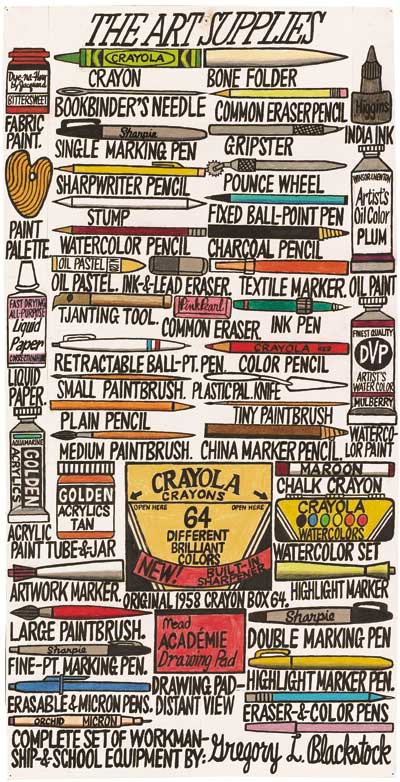

Gregory Blackstock, The Art Supplies The depths of Blackstock’s knowledge and memory is really quite something. So vast and varied is it, the illustrated guide to his work, ‘Blackstock Collections,’ sees it imperative to categorise such a huge number of works under different headings – ‘Fish I like,’ ‘The Tools,’ ‘Architectural Collection,’ ‘ The Noisemakers,’ ‘Our Famous Birds.’ This way, we are able to make better sense of this one man’s awe-inspiring encyclopedic knowledge.

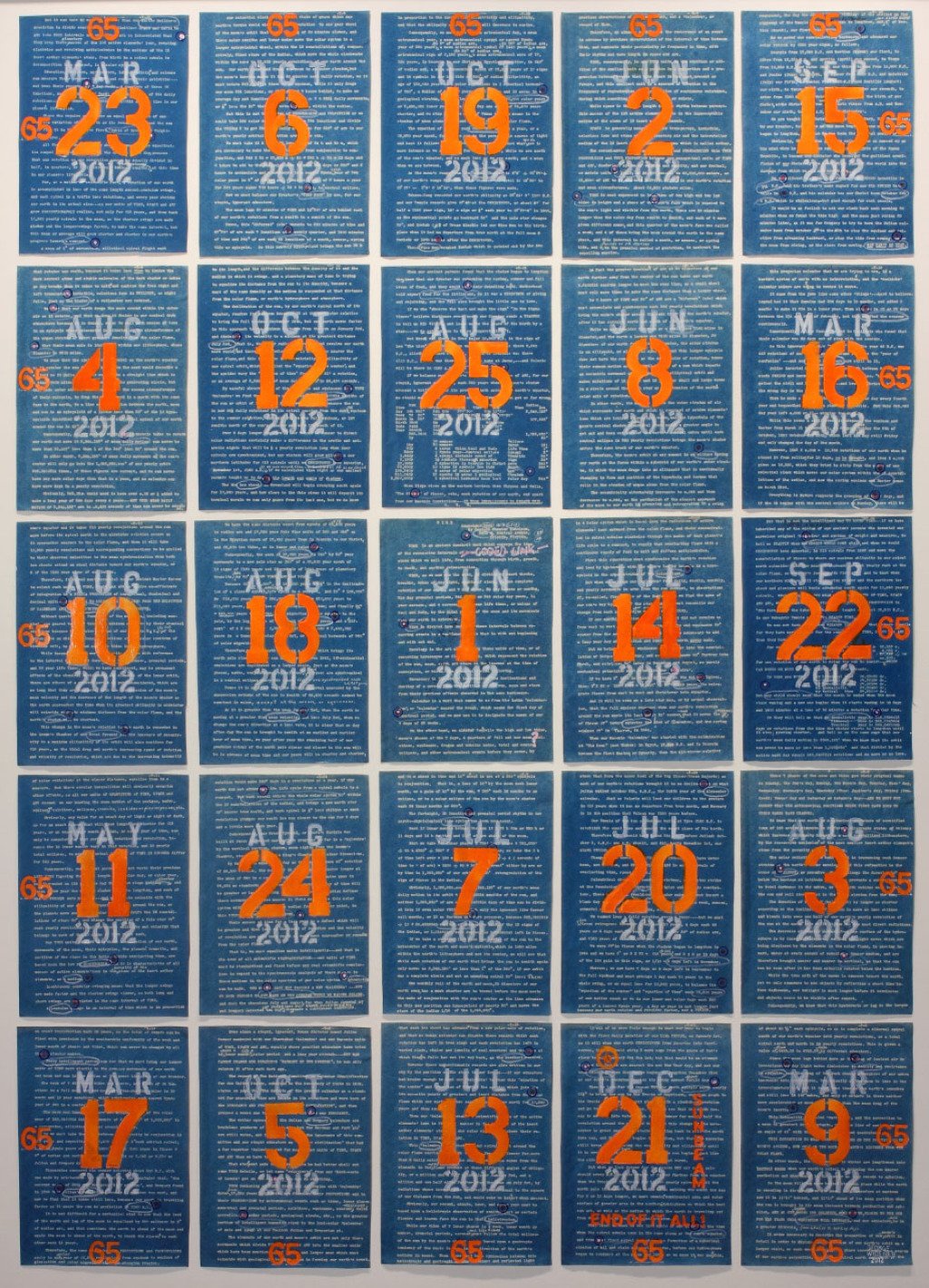

George Widener, another – equally prolific – savant, was represented in the Hayward Gallery’s ‘Alternative Guide to the Universe.’ Widener’s brain has been proven to function like a super-calculator; allowing him to process information in a wholly different way to the majority of people.[4] His favoured method of communication is the calendar format. His calendars help him to consider time and space in a linear pattern, and they often refer to historical events – like the sinking of the Titanic, but they can also be made up of registration plates or telephone numbers.[5]

George Widener, Megalopolis, Image courtesy of the Henry Boxer Gallery More of a craftsman than an artist per se, James Henry Pullen carved and built ships inspired by his childhood fascination with watching his peers play with toy boats in little puddles. During his lifetime, Pullen became incredibly skilled in his making of these ships, reproducing them in pencil drawings, earning himself the title of ‘the Genius of Earlswood Asylum.'[6] He even attracted the attention of King Edward VII, who began sending him tusks of ivory to work with, and Sir Edward Landseer, who sent him engravings of his work to copy.[7]

James Henry Pullen, Image courtesy of the Down’s Syndrome Association Esther Brokaw’s early interest in art was encouraged by her Aunt Lois, who took her to visit galleries and bought her art materials during her youth. For forty-four years of her life, Brokaw went undiagnosed. It was only in 2004 that her diagnosis helped her to understand her equal obsessions with painting and stock market charts. Brokaw paints in acrylic, watercolour and oil from photographs she has taken herself. She is renowned for her immaculate detail when it comes to depicting every leaf on a tree, or every beam of light cast down from the sky.[8]

Esther Brokaw, Image courtesy of the Good Purpose Gallery The above artists are just four examples of the incredible ability of people we call ‘savants.’ The Wisconsin Medical Society, which I have utilised heavily for this post, has a more inclusive list of savants – both artistic and non-artistic.

Despite its association – for me anyway – with religion and spirituality, the term savant is a celebration of unparalleled ability amongst people who have been diagnosed as having a form of ‘disability.’ The awe-inspiring memory and inimitable attention to fact and detail is a testament to human skill and creativity. The fact that many savants choose creative methods to express their extraordinary knowledge is also testament to the power of creativity. The power it has as a vessel for sharing and expression, and the power it has to raise awareness of the uniqueness of the human condition.

George Widener, Magic Square, Image courtesy of Artspace

References

[1] Wisconsin Medical Society – The Artistic Autistic Savant

[2] Roger Cardinal, Outsider Art and the autistic creator, 2009 (available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2677583/)

[3] Blackstock’s Collections (2006), p10

-

A Note on Outsider Art

On 31st May, I was very kindly invited to give a talk at the ‘Life is Your Very Own Canvas’ mid-exhibition event in Aberdeen by organiser of the show, Steve Murison. The exhibition showcased work by people who are part of the Penumbra Art Group in Aberdeen. I spoke briefly about outsider art and how I had become interested in it, and what I was doing now to support artists who might be considered ‘outsider.’ Although the talk was brief, I took some time in the run up to refresh my memory on all things outsider art – which I thought I would put together in a blog post.

Gaston Chaissac

My prior research took me back to when I first starting studying outsider art – right to the beginning, to quotes from Jean Dubuffet and Roger Cardinal. I’m going to split this post into four different sections, just to put my thoughts down on paper (or computer): a brief history of outsider art, what it is today, my interest in outsider art, and what I think about outsider art now.

First things first, the exhibition was absolutely extraordinary. Many of the artists with work on the wall had never picked up a pen or a paintbrush before joining the art group, and many had re-found their creativity many years after losing it to illness or life events. There was a mixture of 2D pieces, including a series of ‘diary drawings’ illustrating the artist’s daily life in and around the city of Aberdeen, and 3D pieces; like a jaw-dropping papier mache dragon. It was inspiring to meet many of the artists at the event, who were all incredibly proud (as they should be) at having their work hanging in the exhibition.

Norimitsu Kokubo

The History

So, let’s start at the beginning. The initial emergence of outsider art occurred between the ‘Golden Years’ of 1880 and 1930. The term itself was coined by art historian Roger Cardinal in 1972 as an English equivalent to Jean Dubuffet’s ‘Art Brut’ or Raw Art, which was coined in the 1940s. When describing work as ‘Art Brut,’ Dubuffet meant work that was untouched and untainted by traditional artistic and social conventions. In his manifesto Art Brut in Preference to the Cultural Arts (1949) he says:

“We understand this term (Art Brut) to be works produced by persons unscathed by artistic culture, where mimicry plays little or no part. The artists derive everything – subjects, choice of materials, means of transposition, rhythms, styles of writing etc. – from their own depths, and not from the conventions of classical or fashionable art.”

Dubuffet’s collection of Art Brut is housed in the Collection de L’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, for which there is (still) a very strict acquisitions criteria. The museum’s acquisitions are based on the following five characteristics: social marginality, cultural virginity, the disinterested character of the work, artistic autonomy, and inventiveness. There are, of course, contentious ideas within Dubuffet’s strict – and marginalising – criteria. It is incredibly difficult, even so in the early 20th century, for someone to be completely detached and separated from culture in all its forms.

Take for example some of the most famous outsider artists. Adolf Wolfli worked as a farm hand in his early life; Scottie Wilson was in the armed forces, travelling to both South Africa and India; and Henry Darger worked for most of his life as a caretaker.

Dubuffet’s Art Brut is idealistic, it is not realistic. And this is where some of the contentions and debates arise around the term and what it stands for – back then and still today.

Henry Darger

Outsider Art in the Present Day

Throughout the 20th Century, the term gradually gained momentum. It is still around today, although in a very different form to Dubuffet’s Art Brut. Today, it is more of an umbrella term for work that is created outside of mainstream culture – and includes terms like ‘self-taught art,’ ‘folk art,’ ‘intuitive art.’

Everyone in the field has their own idea of what it means – a popular one being that anyone who calls themselves an outsider cannot be considered an outsider artist. Originally, outsider art was taken from the homes of artists on the sad happening of their death (like the famous story of Darger whose work was found when his apartment was cleared following his death, whence his tomes of The Vivien Girls books were uncovered).

And then, of course, there is the divide between mainstream and ‘outsider’ art. At what point does an outsider artist become an ‘insider’ artist? Dubuffet was known to have ‘ex-communicated’ one of his own discoveries, Gaston Chaissac, because of his contact with ‘cultivated circles,’ and Joe Coleman was expelled from the 2002 New York Outsider Art Fair in which he had taken part since 1997 because he had been to art school and had ‘become too aware of the whole business process of selling.’

A good way to look at it, I think – as it gets very confusing – is how Editor of Raw Vision Magazine, John Maizels talks about it in his book Raw Creation: Outsider Art and Beyond (1996):

“Think of Art Brut as the white hot centre – the purest form of creativity. The next in a series of concentric circles would be outsider art, including art brut and extending beyond it. This circle would in turn overlap with that of folk art, which would then merge into self-taught art, ultimately diffusing into the realms of so-called professional art.”

Scottie Wilson

My Journey with Outsider Art

My own interest in outsider art first started when I was at university. I studied History of Art, and – surprisingly – we had a whole module on outsider art. Well, it was actually a module on psychoanalysis and art, but the term outsider art kept cropping up, and I was curious. To help with my paper for this module, I visited Bethlem Museum and Archives to look at the work of Richard Dadd. I immediately found myself immersed in this world of raw human creation.

Outsider art for me often comes straight from within. It’s not made for a market and it doesn’t come out of art schools (although I am certainly not adverse to people who have been to art school aligning themselves with outsider art). It inspires me because one of the most innate and unique things about being a human being is our ability to be creative. I think there is nothing that illustrates this better than outsider art.

I went on to write my BA Hons dissertation on the links between German Expressionism and outsider art and was not surprised to find that many art movements in the twentieth century were inspired by the work of outsider artists – including the Surrealists and German Expressionists. Artists at this time wanted to capture the intuitive spontaneity of this work to represent the turbulent times they were living through.

I went on to study for an MA in Art History and by this point was focusing solely on outsider art. I wrote my extended dissertation on the ethics of exhibiting and curating work by outsider artists. For me, it was interesting to think about how ethical it is to display work by someone who never intended for it to be seen. I would think about Henry Darger and his Vivien Girls. He had created this whole world in private – surely it should have been kept private? But if it had been, we wouldn’t have had access to this astounding feat of imagination – maybe the books would have been destroyed?

I continued my research, thinking about the different ways the work could be displayed to best exhibit its aesthetic and inspirational qualities. Should interpretation include a note on the artist? Should the work stand on its own? There seemed to be so many questions that kept on breeding more questions.

Ever since I finished my MA four years ago, I have been working with various projects and organisations that promote or support artists facing some kind of barrier to the art world – whether that barrier is their health, disability or social circumstance.

Aloise Corbaz

What do I think now?

For me, the term outsider art should be redundant. It shouldn’t be outsider art – it should just be art. Sometimes, people and artists need a little bit of extra support to get their work out there, and for this reason I think it’s vital to have organisations and projects like Outside In and Creative Future, but I think the next chapter is to challenge the impenetrable art world.

Why is it so difficult for people to break into the art world if they haven’t been to art school? Who gets to choose what is and isn’t art? For me, outsider art is the bravest form of art. It is defined by artists exposing themselves on paper, in clay, on film, in words, and then sharing it with the world. It’s all about creativity, raw intuition, and the uniqueness of being human – and it can certainly teach us all a lot about humanity!