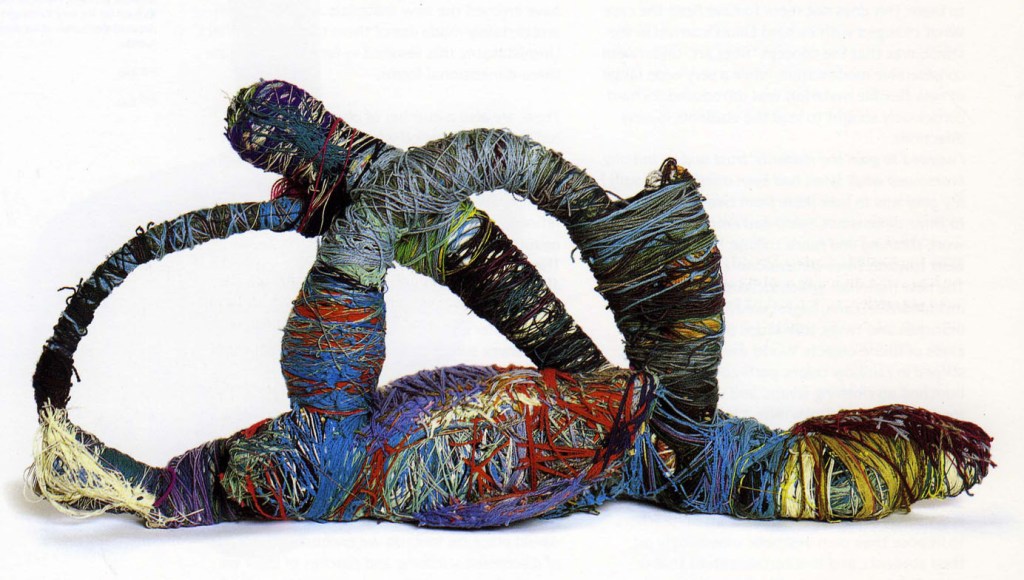

Above Image: Jean Dubuffet, ‘Les Vicissitudes’, 1977 (Source: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T03679)

I handed in my MA dissertation just over two months ago – and only now do I finally feel ready to return to it to blog about some of the queries it raised with regards to ‘outsider’ art (including but not limited to ethical issues, problems facing curators and, of course, the infinitely ambiguous definition of the term). One of the main questions I found myself focusing on when I began writing, was the issue of voyeurism; who gains what from viewing the work of ‘outsider’ artists. This ‘issue’ as such became a question to which I changed my mind about somewhere around 100 times during the writing process.

“Though Outsiders expect nothing from us, not even our attention, we steal upon them like eavesdroppers.”[1]

During the nineteenth-century, the time when the idea of art and ‘madness’ was first being explored by the Romantics, the relationship between the two was curiously idealistic. This unquestionably romantic view of madness was rarely based upon any real experience of insanity, but was rather a fantasy of madness; an idea of a wild, untameable, unbridled creativity. From this early on, we can see the beginnings of a voyeuristic interest in the work of those who were perhaps marginalised from society. Even Hans Prinzhorn’s Artistry of the Mentally Ill, published in 1922, focused more on the art of psychiatric patients as a pathological endeavour as opposed to an aesthetic one. There is, afterall, no stylistic guidelines with regards to the definition of the term ‘outsider’ art itself, meaning there is often more interest in the artist than in the work as a reason for ‘classification’ as an ‘outsider.’

Despite my initial thoughts focusing more on the possibility of potential voyeurism, I soon decisively changed my mind – I have even written a blog post on how continually worrying about the presence of voyeurism can perhaps affect the accessibility of ‘outsider’ art exhibitions for those with little to no prior knowledge of the subject.

“Why look at outsider and self-taught art, if not out of romantic nostalgia for some image of unfettered individuality and expressive freedom? Or is our fascination with this art just one more form of voyeurism?” [2]

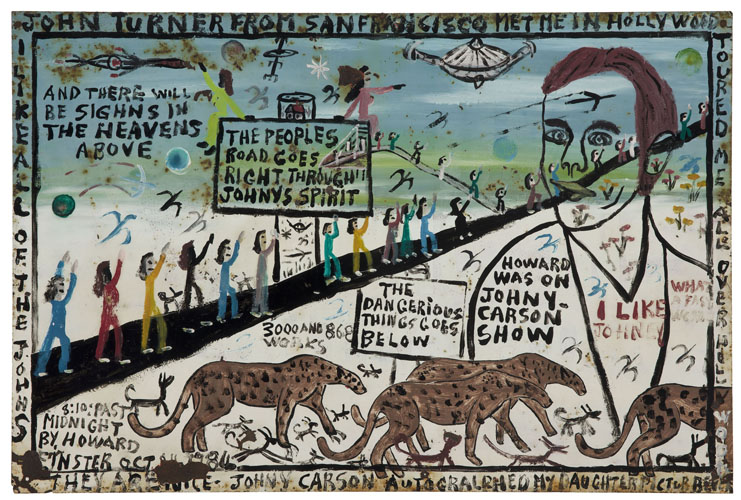

Just yesterday, conincidentally enough, I came across this article, in which Ian Patel asks who exactly benefits from ‘outsider’ art. The article, similarly to my initial thoughts about ‘outsider’ art exibitions being steeped in potential voyeurism, suggests that there are “many ethical questions surrounding the public display of art produced by what might be termed ‘vulnerable adult’ constituencies.” Patel continues, saying that “such exhibitions tend to go unquestioned as a positive force for both participating artists and the viewing public,” and that “participating artists are assumed to benefit from artistic recognition.”

The article goes on to suggest that there are perhaps deeper ethical questions to consider with regards to the “public consumption” of marginal art. Patel considers The Koestler Trust – whose work he claims at first glance could appear as a “voyeuristic thirst for productions rooted in human degradation, infamy and shame.”

Although the article does move on to talk more about how marginal art exhibitions can act as a “powerful advocacy tool,” I was interested in how voyeurism is often a recurring theme with regards to the subject of ‘outsider art.’

Voyeurism, in my opinion, is a very dangerous word when considering what people get out of ‘outsider’ art. I can’t speak for everyone – but I can tell you what I get out of it. I studied History of Art at undergraduate level and two months ago, I completed an MA in Art History and Museum Curating. I think somewhere along the way, I got dissillusioned with the ‘mainstream’ art world (contemporary in particular). I have always believed that creativity is not something you can learn – going to art school isn’t going to teach you how to be creative, or imaginative. I also think it is not something that should work like a production mill for monetary gain. I think it is something innate, something that makes us human. I do, however, believe that everyone has the capacity for creativity. Art should be for everyone, not just those with an Art History degree, or a Fine Art degree for that matter, and ‘outsider’ art helps me to appreciate this. For me, there’s nothing like being blown away by a work of art created by someone with no formal training – someone who has produced a piece based on a feeling or raw creative intuition; something that can’t be put into words. Something that is a reflection of humanity and a portrayal of these feelings which make us human, rather than a creation made for commercial interest or capital.

For me (and Patel also notes this too), public exhibitions are often not the “end-goal” of community art programmes. It is the therapeutic effect of creating and producing that should be celebrated – the final exhibition is just a space to share this. Increasing inclusivity within the art world is a whole huge leap towards a more generally inclusive society, and shunting this merging of the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ (whoever gets to decide these terms) by using the term ‘voyeurism’ will only delay the process.

References

[1] V. Willing, ‘Out of Order’, in In Another World: Outsider Art from Europe and America Exhibition Catalogue, 1987.

[2] Lyle Rexer, How to Look at Outsider Art, 2005.

Response to article ‘Outside Looking In’ by Ian Patel, published at www.artsprofessional.co.uk

![Self-[Other]_PointBarracks_installation_view](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/self-other_pointbarracks_installation_view.jpg?w=640&h=178)