I asked artist Brian Gibson for his thoughts on the term ‘Outsider Art’ and what it means to him as a practising artist. Below is his response and a display of his own artwork. Click here for more information on Brian and his work.

I have never been quite certain as to where I fit as an Artist. For a long time the thought of being an artist felt very alien to me, it was after all another culture. Artists were clever, confident, sophisticated and well educated people. That was not how I saw myself; I was just some lone youth from a council estate on the outskirts of Newcastle from a single parent household who had a history of truancy with little to show in terms of qualifications.

On the domestic front it was my Father who could draw, he was very gifted, he could draw calligraphy free hand or paint golden Celtic knots or Spanish dancers onto painted egg shells and all sorts of other intricacies. He was a gifted man who never really dared to share or show his talent beyond the garden gate. In comparison my creative efforts were never so precise. My handwriting was spidery and I never could quite get the hang of perspective; such things didn’t come natural to me, so the notion of becoming an artist wasn’t even on the radar for me. However there was a creative flame that flickered within me and I was fortunate that my efforts were never discouraged and even if the end results often fell short of how I wanted things to be, I was at least able to lose myself in what I would later know as “the creative process.”

Art became less of an alien culture, as I got to know various accomplished works of art via my regular city visits to the art galleries and libraries when absconding from school. Also importantly for me was the fact that I had met someone who had decided to embark on their own creative path; he was a poet by the name of Barry MacSweeny. He lived on the adjacent Council Estate and was the elder cousin of two of my school friends, so occasionally we could find him in his mother’s kitchen writing away whenever we called round for a biscuit and drink of pop. As one of the emerging 60’s poets, his first book of poems was published when he was just 19 years old. Being older he didn’t have much to do with us, appearance wise he looked a bit like Terry Collier from the TV series “The Likely Lads”; dapper and wiry.

Having known such a person in my youth left a simmering impression on me. Why I mention him here is that he chose to do something creative and that was influential for me and secondly, if he were a visual artist he might now be considered posthumously to be some kind of Outsider. Although he never went to University, he was nominated for the poetry chair at Oxford. This however turned out to be just a cynical publicity stunt concocted by his publisher. This humiliation along with his own personal demons contributed to him remaining a marginalised poet for over 25 years. He died in 2002 aged 52.

The original definition of term “Outsider” set out by Roger Cardinal back in the 1970s seems to have evolved and undergone a seismic transformation in recent years, particularly with the expansion of social media. Such connectivity has meant that creative people working outside the mainstream are no longer so dependent on the nod of the well informed to decide whether this or that piece is an actual work of art.

Now individuals can link up with other individuals, share ideas, post up images, form groups, put together exhibitions and even sell their work. Autonomy, self-empowerment and money – it all sounds rather good but the reality may be a little different. To be an Outsider Artist seems to have become incredibly fashionable of late, numerous tee-shirts and accessories in Selfridges and articles in Sunday supplements seems to be of good indicator of this.

Outsider Art is now being presented as the more rebellious sibling to the established world of fine art, with Folk art the more amenable earthy but less noteworthy cousin. Outsider Art is more rock and roll, more edgy, and people are proud to wear their Outsiderness like a badge of honour. Now and this may not be a bad thing but I am aware that anyone can get in on the act. I have seen a lot of savvy websites by individuals where the work veers into being more about a product in a particular style that happens to look like Outsider Art. As a trained artist who was dealing with his or her own mental health issues once said to me: “Outsider Art is easy to fake,” or at least it might seem that way. So a question that I have is “What does it means when such work becomes an entrepreneurial enterprise?”

There are many other questions regarding the increasing popularity and branding of Outsider Art. I can envisage a future where a retailer such as Primark would be either selling tee-shirts cheaply of original prints from acknowledged Outsiders such as Madge Gill or Jean Dubuffett and the like or, more likely – to save on copy write issues – just employing some people to produce something that looks a bit like the work of an Outsider Artist. Is this any more different than buying an original reprint from a more exclusive and prestigious source or to put it another way, who gets the money and what is the money the measure of ?

Despite its current popularity, Outsider Artists tend to be Outsiders for a reason. It may well be that the making of work is the sole or soul reason why a person pursues a creative path, everything else may well be an after thought. The poet Barry MacSweeny could write and he could rant and he had his own demons so there were times when he just couldn’t get much of any thing together. I don’t think that this lessened the quality of his work, but I doubt if it served him very well in getting his work published. This seems to be the reality for a number of visual artists that I know, making the work is one thing, doing the rest is another. The added pressures of presenting work to a public audience to a deadline and dealing with unknown people, along with all the other stuff can be more than enough for most.

For a good while now marginalised individuals and groups have worked hard to put themselves in the frame work so to speak in a way in which they feel represents them in the way that they wish to be seen and valued. It can take a lot of time and thought to develop environments where people feel safe and supported but I am sure that I am not the only one to have heard stories of unscrupulous figures waiting in the wings who are only too willing to put their profit and their own prestige way before the people they purport to represent. Having worked with vulnerable adults for over ten years now, I am just a little concerned that with so many self proclaimed Outsiders seeking centre stage, individuals and groups who have been historically marginalised may once again find them selves out of the picture.

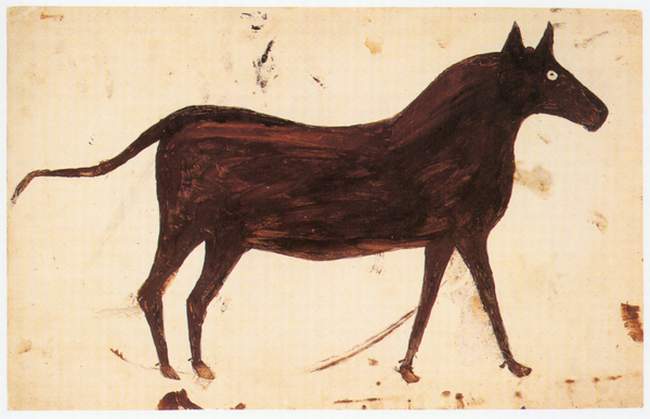

A note on Brian’s work (presented in this blog post):

Earlier this year I produced six pieces with the overall title of “I am frightened and timid and I don’t want to play” specifically for an exhibition as part of Fringe Arts Bath. Some of the works are named after the titles of songs but don’t really have much to do with the songs themselves, if at all.

![Otto Dix, Schädel (Skull), 1924 [Courtesy of: www.deborahfeller.com]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/the-skull-1924.jpg?w=766&h=1024)

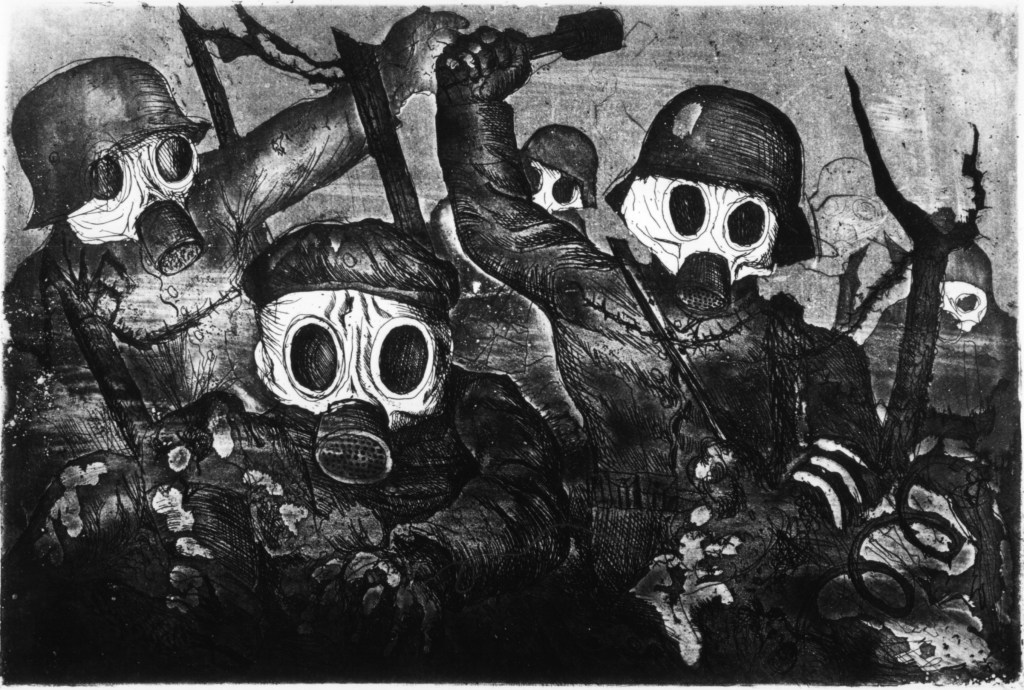

![Otto Dix, Gastpte - Templeux-la-Fosse, August 1916 (Gas Victims - Templeux-la-Fosse, August 1916), 1924 [Courtesy of: www.port-magazine.com]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/gas-victims.jpg?w=640&h=460)