Hugest apologies for such a long absence. Life things have been happening over the past couple of years – including (but not limited to!) becoming a parent and getting my head down to finish my PhD. After six long years, I have now finally completed my PhD research and I am really excited to share this with you over a number of posts on this blog. Please do comment or contact me if you’d like to join in the conversation. I’d really like for this to be a shared space to reflect, ask difficult questions and utlimately look towards reshaping the systems and structures that continue to make the UK art world incredibly exclusive.

(more…)Tag: folk art

-

The Importance of Folk Art

I have just started researching for my next PhD assignment, which will look at the ways the media has reviewed exhibitions of outsider art over the past fifteen years. Whilst working my way through back catalogues of exhibition reviews, I came across Jonathan Jones’ review of the 2014 British Folk Art exhibition at Tate Britain (London).

In his review of the first major exhibition of British folk art (which is actually very positive), Jones identifies folk art as exceptional in that it “shows that there lies a whole other cultural history that is barely ever acknowledged by major galleries.” This got me thinking about a work trip I made to Compton Verney in Warwickshire earlier this year. Compton Verney has its own very broad collection of folk art, which is exhibited in custom designed rooms housed at the very top of a magnificent building.

Incorporating amusing yet beautiful paintings of prized farm animals to visual signs used above shops before reading was something that most people were able to do, the collection is a wonderful accumulation of a history of Britain that we so rarely get to see or experience. It is the day to day life of the everyday person.

Traditionally produced by people from a lower socio-economic background working within their local communities, folk art is often found dancing around the edges of the mainstream art world. Often seen as craft, it has a reputation as being a form of ‘low’ art. The distinction between folk art and ‘mainstream’ art has been emphasised – and embedded – by art institutions, whose historical works endeavour to show either the lives and faces of the upper-classes, or the lives of the working-classes through the eyes of the middle- or upper-classes.

In his review, Jones notes that “where ‘elite’ paintings in the Tate collection might show such people [people from the working-classes] labouring in the fields, here they are shown as they wished to see themselves – dressed up on a festive day instead of working their fingers to the bone.” This distinction between the content of folk art and the content of ‘mainstream’ historical works highlights the influence of art institutions over what we see and know about our own cultural history.

On entering most of the major galleries in London, works in their historical collections will show monarchs, or other men and women of high standing, probably dripping in gold. Or they might show the lives of the lower-classes, but tinged with an authoritative gaze – maybe the people in these depictions are at work, or they are sick. These depictions give us very little insight into the actual lives of people who were not a part of society that was accepted, documented and shared. If we believe what we see in these historical works, we could believe that people from working-classes were just unfeeling toiling machines. But what were their lives really like? What did they enjoy doing? And how did they really see the world?

This is where folk art becomes particularly valuable to us. Because it is in these apparently ‘mundane,’ ‘everyday’ images that we see what life was really like for those who had little to no control over what was recognised as historically important. They are lives and stories that have been hidden by those in positions of power; a kind of propaganda that has shaped how we see our history. And art galleries and museums (being the influential institutions that they are) have had a huge part to play in this. Art, if you think about it, is the only visual documentation we have of ‘what came before.’ If we are only privy to images created and disseminated by those from a certain societal standing, then we only see the world as they experienced it.

“In stately homes from Kenwood to the fictitious Downton Abbey, we are told again and again that Britain’s culture has been shaped down the centuries by the elite, its art collection, it cooks and its gardeners,” Jones notes. This, he says, is just “the view from above.” By exhibiting folk art in our key arts institutions (like Tate, and like Compton Verney), we are giving audiences the chance to experience what everyday life was like for the everyday person. Folk art is an intrinsic part of our history. It is something we cannot afford to lose.

(all images taken by the author at Compton Verney)

-

The ‘Integrated Professional’ and the ‘Naive Artist’

My previous PhD research-inspired post, ‘The Cycle of Cultural Consumption’, focused mainly on what sort of culture audiences ‘consume’ and why. It looked at Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of habitus, and how our social and educational background is the biggest influencing factor when it comes to the culture that is available – and interesting – to us. As I continue to read and research, I have turned my attention now to artists and their relationship with the art world. So, rather than a focus on audiences, I am looking at producers and how they interact and integrate with the ‘art world’ as a system.

I have recently been reading two books – Gary Alan Fine’s ‘Everyday Genius: Self-Taught Art and Culture of Authenticity’ and Howard S. Becker’s ‘Art Worlds.’ Fine’s book focuses almost exclusively on work by self-taught artists, whereas Becker’s sociological insight into art worlds and how they work is slightly broader, encompassing not just visual art, but other media too. It is Becker’s broader text that I will reference in this post, as it gives more of a contextual overview of the art world and its players. I will return to Fine’s book in a later post.

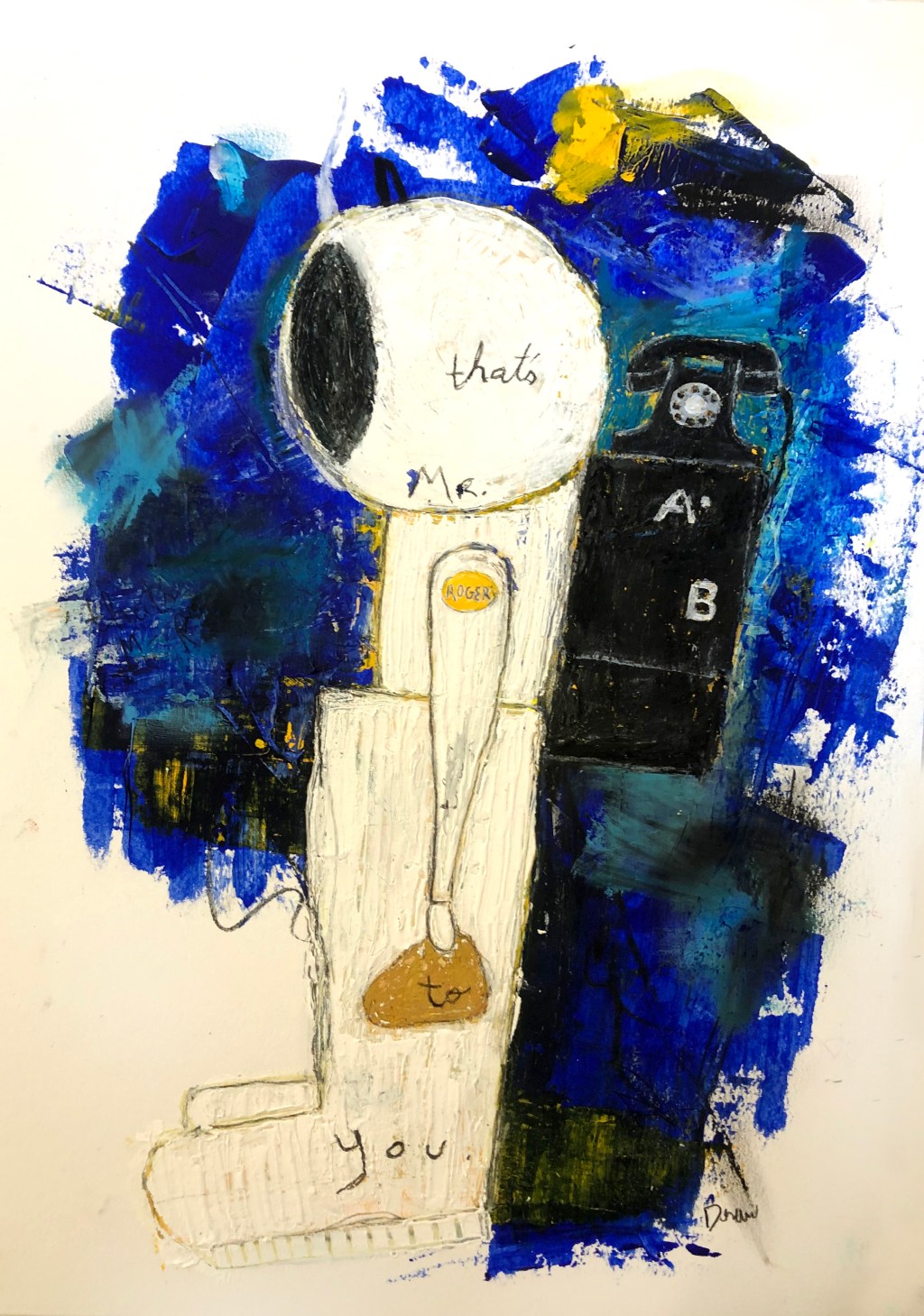

Poucette, Longchamps (courtesy of http://www.artnet.com) The art world – and in this case, I am referring to the art world as the art schools, galleries, museums, curators, critics, and media outlets that make up what we would ‘traditionally’ and ‘conventionally’ see as the art system – is based on an historical, standard system of acceptance. Artists are generally expected to attend art school, following this, they might find representation from a gallery or dealer, in turn having their work exhibited in museums, galleries and online. There is this unconscious system constantly ticking over, and only a few are privy to the pattern. As Becker says: “How do we know the pattern? That takes us out of the realm of gestalt psychology and into the operations of art worlds and social worlds generally, for it is a question about the distribution of knowledge, and that is a fact of social organization.” [1]

In ‘Art Worlds,’ Becker describes four main types of artist – the ‘integrated professional,’ ‘the maverick,’ ‘the folk artist,’ and ‘the naïve artist.’ The integrated professional is someone who has journeyed the correct way through this system. They follow the rules when creating their work, and in turn, their work is accepted by art world aficionados. They don’t create anything too surprising, too unexpected, and this is all great – nothing to upset the status quo here. The title ‘maverick’ refers to “artists who have been part of the conventional art world of their time, place, and medium but found it unacceptably constraining.” [2] So these are artists who have entered the art world in the traditional and ‘respected’ way at some point, but have decided it’s not really for them. They know the system, they know how it works, but what they make – or what they want to make – goes against the accepted norm. I guess in a sense you could consider Marcel Duchamp a maverick (although in some respects his impact on the art world as a whole makes him less of a maverick in Becker’s sense and more of an influencer).

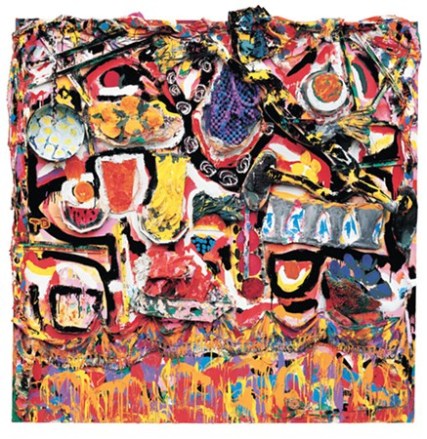

Henri Hecht Maik, Marché dans les Hautes Herbes (courtesy of http://www.artnet.com) This leaves our ‘folk’ artists and our ‘naïve’ artists. Becker’s understanding of a ‘folk’ artist differs slightly from the ‘folk’ artist we might associate with outsider art. He refers mainly to quilt-makers, and people who have learned particular techniques and crafts from their families or communities. His term ‘naïve’ artists probably more closely aligns with our current outsider art category. These artists “create unique and peculiar forms and genres because they have never acquired and internalized the habits of vision and thought professional artists acquire during their training.”[3] Interestingly, Becker says of the terms ‘naïve’ and ‘folk’ that they do not relate to people. Instead, they refer to the position a person holds in relation to the ‘accepted’ art world. He notes that “wherever an art world exists, it defines the boundaries of acceptable art, recognizing those who produce the work it can assimilate as artists entitled to full membership, and denying membership and its benefits to those whose work it cannot assimilate.”

In many cases, the ‘integrated professional’ is the safe bet. They are someone who knows the system, their work aligns with what is expected; it fits into the canon. Imagine, Becker asks, “a canonical artist, fully prepared to produce, and fully capable of producing, the canonical art work. Such an artist would be fully integrated into the existing art world. He would cause no trouble for anyone who had to cooperate with him, and his work would find large and responsive audiences.” [5]

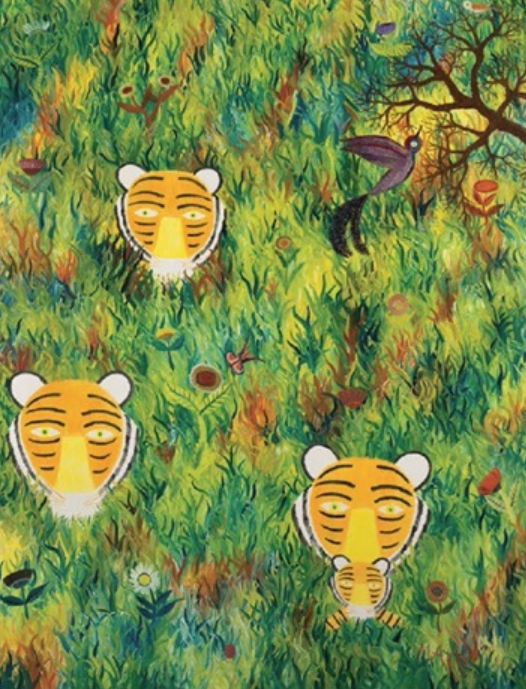

Marc Chagall, Le Repas des Amoureux (The Romantic Dinner) (courtesy of http://www.artnet.com) So, yes, a safe bet. But is it the right bet? How do we challenge this? My favourite question: who gets to decide? Well, it is, it seems, the decision of those who have travelled the ‘integrated professional’ route: “conventions known to all well-socialized members of a society make possible some of the most basic and important forms of cooperation characteristic of an art world.”[4] Becker mentions Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s discussion of the standard of taste, “when he remarked that while what made art great was a matter of opinion, some opinions were better than others because their holders had more experience of the works and genres in question and so could make finer and more justifiable discriminations.”[6]

All decisions are made by certain people at a certain point in history. Decisions about whether a piece of art is accepted into the art world generally has no relation to the aesthetic quality of the work. We know this because “art worlds frequently incorporate at a later date works they originally rejected, so that the distinction must lie not in the work but in the ability of an art world to accept it and its maker.”[7]

Minna Ennulat, River Scene Hamburg (courtesy of http://www.artnet.com) All of this thinking about systems and how we mould ourselves to fit them – not just the art world, but a whole host of other societal systems (the education system for one) – had me thinking about something someone said at a conference I attended last week. The conference was about collections of patient created art work in Europe, and so there was a strong focus on mental health, stigma, and the ethical exhibiting of work by people who historically were ‘locked up’ in huge psychiatric institutions. In one session, one of the panellists said that a person experiencing mental health issues shouldn’t be attempting to fit in to a societal system that has been created by ‘well’ people. (It is like that age old adage – if you spend your whole life trying to teach a fish to fly, it will always feel like a failure). Instead, we should seriously be thinking about how our societal systems work, and within these existing systems, we should be consciously making space for people who for whatever reason don’t – or can’t – fit what we consider to be the ‘norm.’

“Who tries things first? Who listens and acts on their opinions? Why are their opinions respected? Concretely, how does word spread from those who see something new that is worth noticing? Why does anyone believe them?”[8]

Thank you for taking the time to read this post. As part of the PhD research process, I am really keen to hear from anyone who has any thoughts on the subjects I am covering in these posts – whether you agree, or strongly disagree! I am particularly keen to hear from artists about their experiences of trying to enter the ‘art world’ (whether this has been positive or negative). You can drop me an email: kdoutsiderart@yahoo.com, or send me a tweet: @kd_outsiderart.

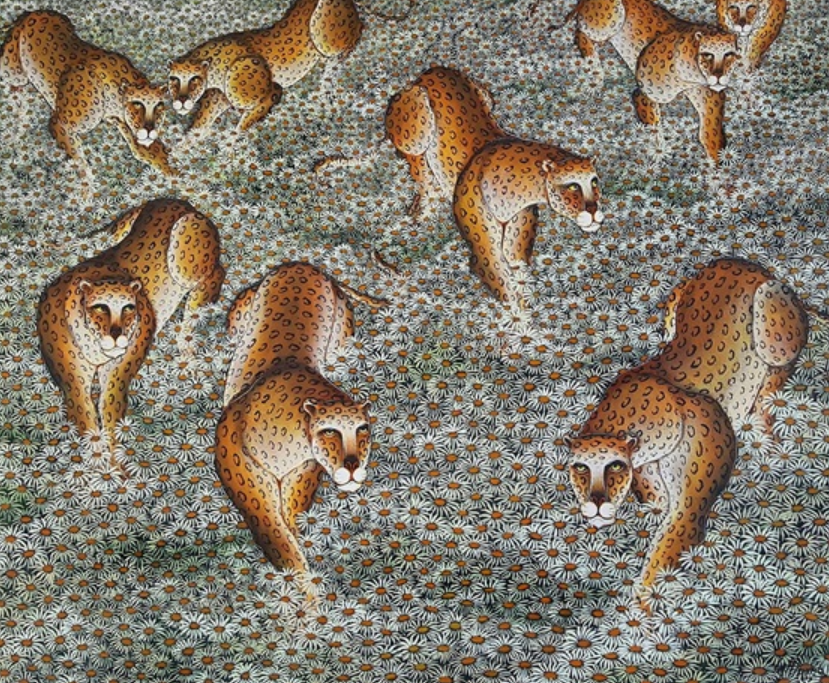

Gustavo Novoa, Daisy Trail (courtesy of http://www.artnet.com)

References

[1] Howard S. Becker, ‘Art Worlds,’ University of California Press, 1984, P 41

[2] Becker, P 233

[3] Becker, P 265

[4] Becker, P 46

[5] Becker, P 228-229

[6] Becker, P 47

[7] Becker, P 226-227

[8] Becker, P 55

-

Curtis Fairley: Animals and Inventions

This is the final installment in a series of posts introducing American artist Curtis Fairley. In this post, collector and supporter of Fairley’s work, George Lawrence, will focus on Fairley’s depictions of animals and inventions.

.

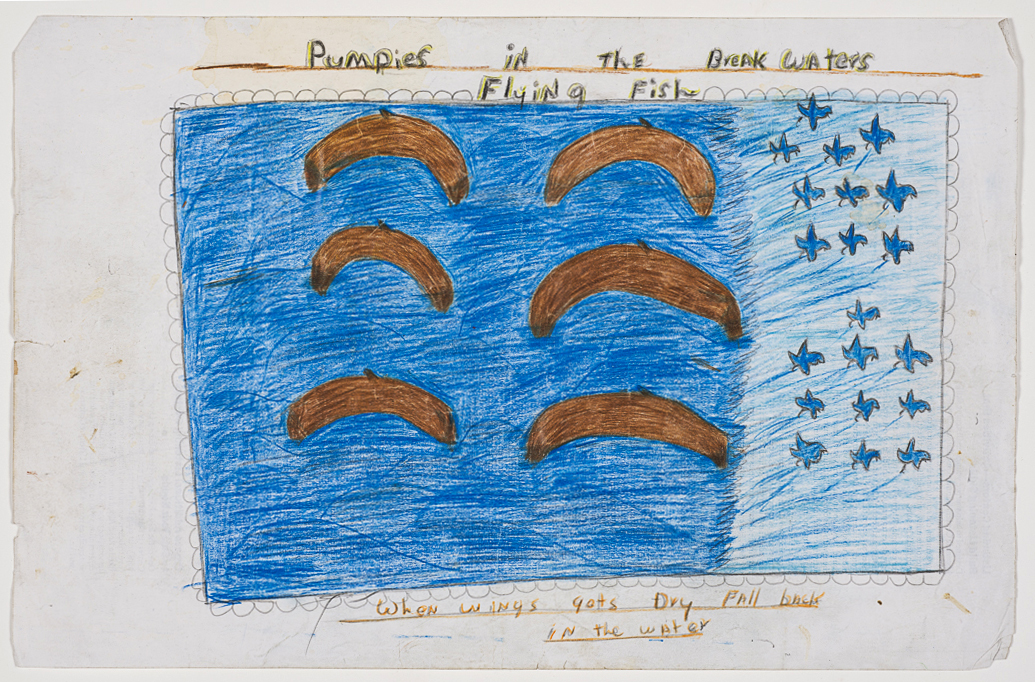

Image 30 – Pumpies in the Breakwaters – Flying Fish ‘

Image 31 – 1987

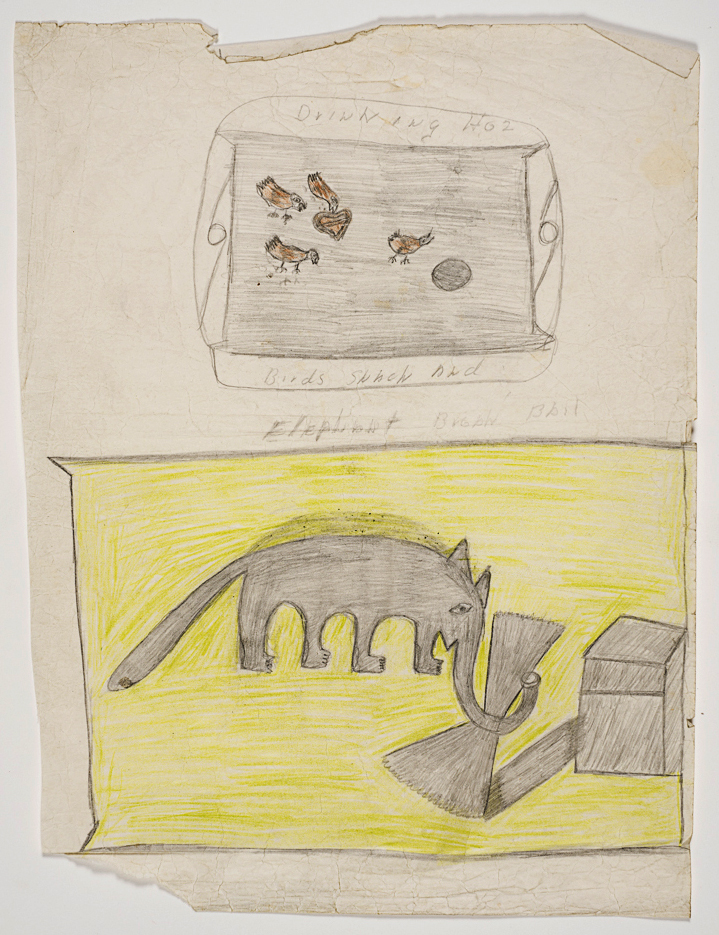

Image 33 – Cat Pulls

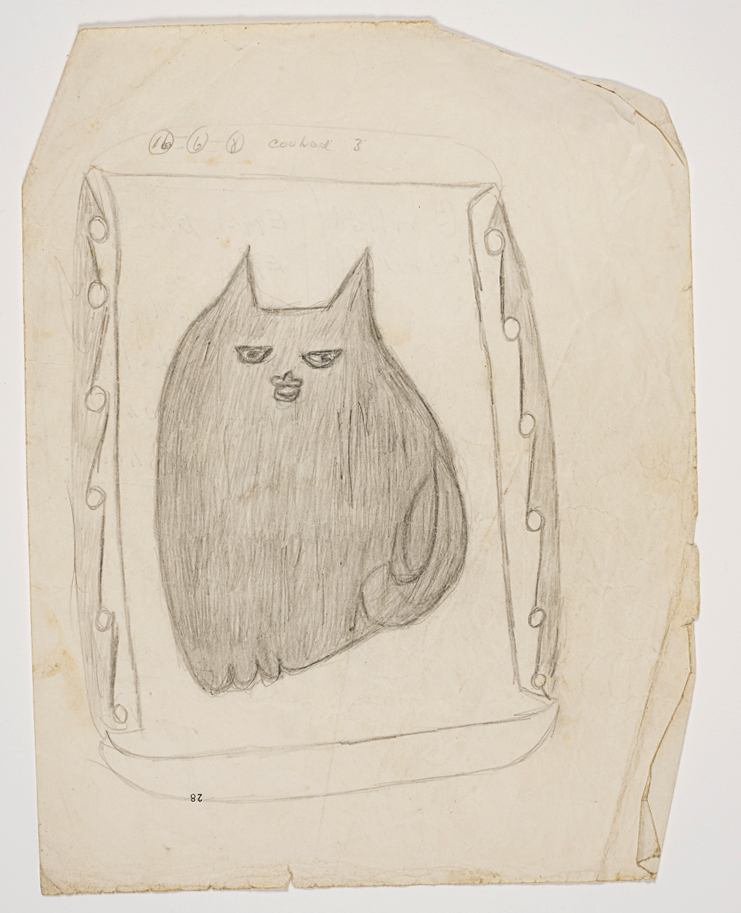

Image 34 – Cat

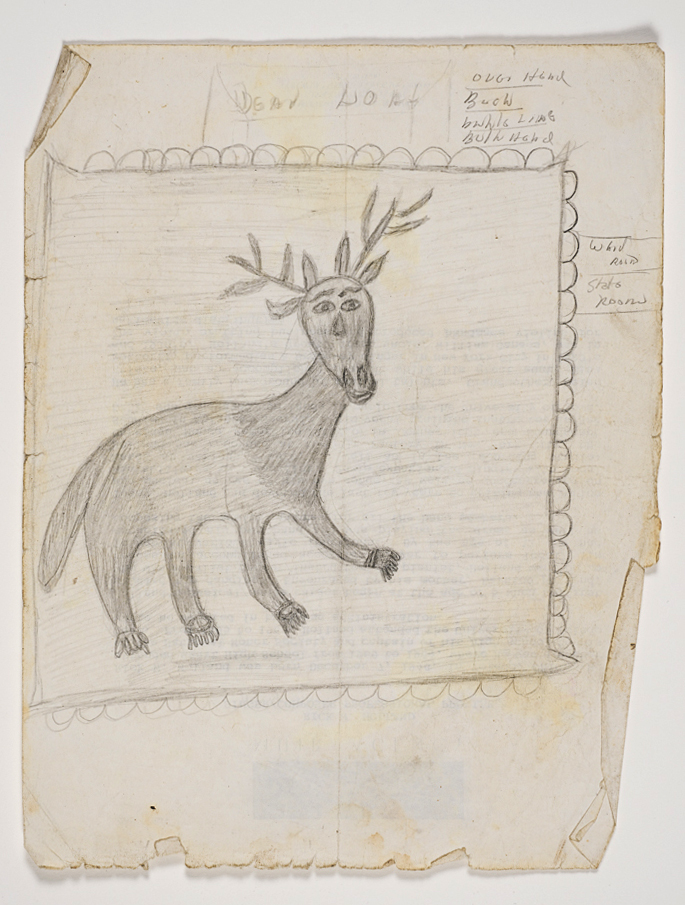

Image 35 – Deer

Image 36 – Starfish

..

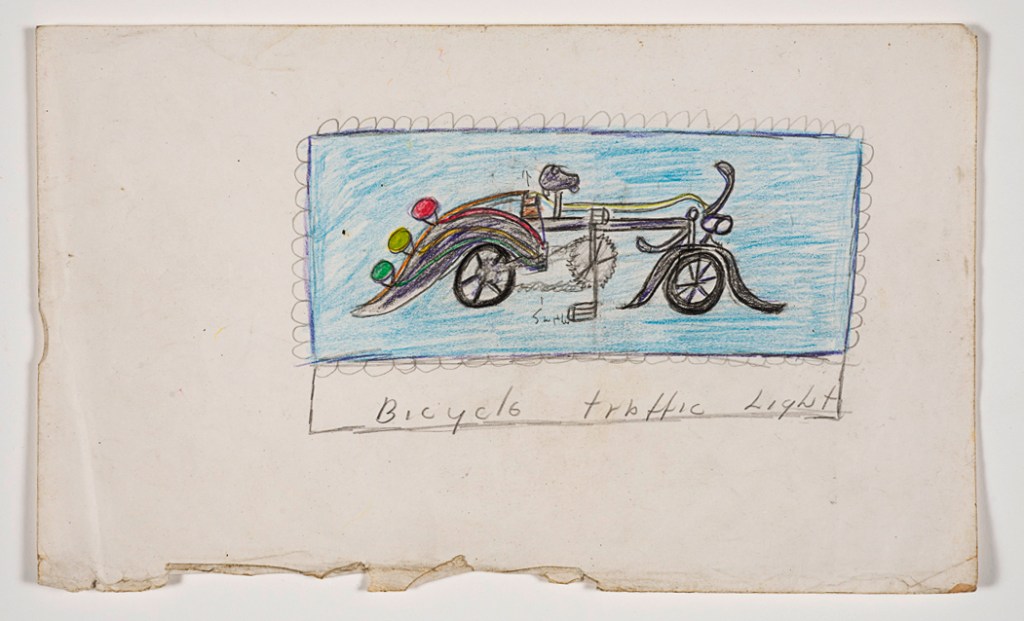

Image 37 – Bicycle Traffic Light

Image 38 – Windmill Powered Oven

Image 39 – Windmill Powered Oven and Traffic Bicycle

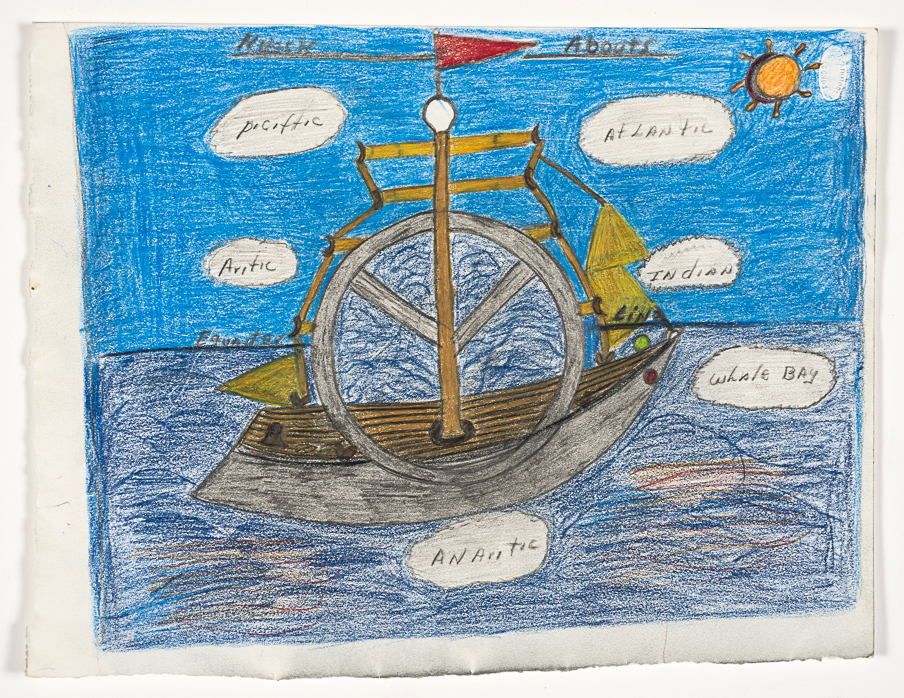

Image 40 – Knock Abouts This is the final installment of a four part series focusing on American artist Curtis Fairley. To read the previous posts in the series, please visit the links below:

-

-

Curtis Fairley: Everyday Life

This is the third post in a series introducing artist Curtis Fairley through interviews with George Lawrence, who is a collector and supporter of Fairley’s work. This post focuses on Fairley’s representations of every day life, and how these are intertwined with his life in the US Navy.

4. Fairley and everyday life

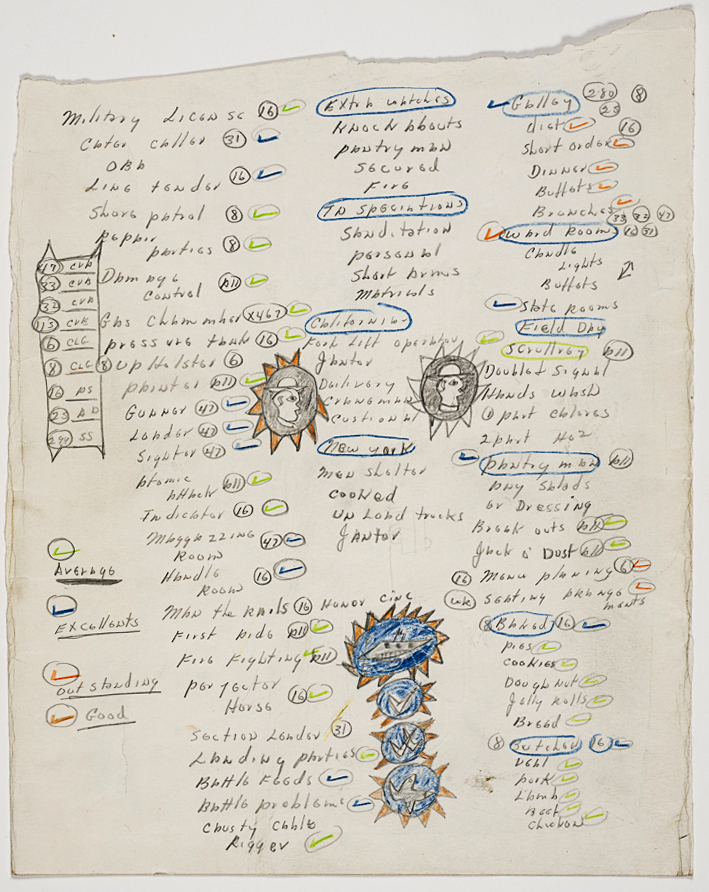

Kate Davey: His naval works certainly are incredibly interesting, and go some of the way to putting Fairley at certain points on the map at various points in his life. Some of his other work – the work that appears more ‘everyday’ actually still relates to his life in the Navy. What are your thoughts on these more everyday works? Is it a desire of Fairley’s to document everything he sees and experiences, from the historically important to the relatively ‘mundane’?.George Lawrence: There are very few of Fairley’s drawings in my collection that I would categorize as ‘everyday’ unless you qualify it ‘everyday in the Navy.’ I think that the years of military service dominated his thoughts and influenced the subject matter of almost all of his artwork. When you think about it, Fairley entered the Navy in 1945 at the age of 18 and then spent the next 31 years in active service and the reserves. It’s easy to see why the main focus of his artwork would be fixed on those years..Apparently, Fairley’s days were filled with a wide variety of duties and tasks. On the back of one of his drawings he made a list of the different skills and positions that he practiced over the years, some of which he has rated according to how well he performed them, in a kind of graphic resume (Image 19).

Image 19 The over 100 listings are almost all jobs and positions that he held in the Navy. The ones he has rated “Outstanding” and “Excellent” include Galley, Ward Room, Pantry man, Baker, Butcher, Gunner, Loader , Sighter. Jobs rated as “Average” include Shore Patrol, Atomic Attack, Pressure tank, Landing parties and Scullery..From what I have read about the Navy in the 1940’s, African-American servicemen were mostly restricted to job postings such as Steward or Mess Attendant. This appears to have been the case for Curtis when he joined in 1945. However, formal racial segregation in the armed forces was ended by President Truman in 1948 and from Fairley’s listing it appears that his opportunities may have expanded over the years to include other duties and responsibilities..Nevertheless, it appears that he took great pride in his position in food preparation and as cook, baker pantry man and butcher. Many of the ‘everyday’ images that you mention, Kate, look like they are representations of some of the meals and dishes that he prepared in the service. One of my favorite images is ‘Stuffed tomatoes Salads w/ Russian Dressing’ (Image 20).

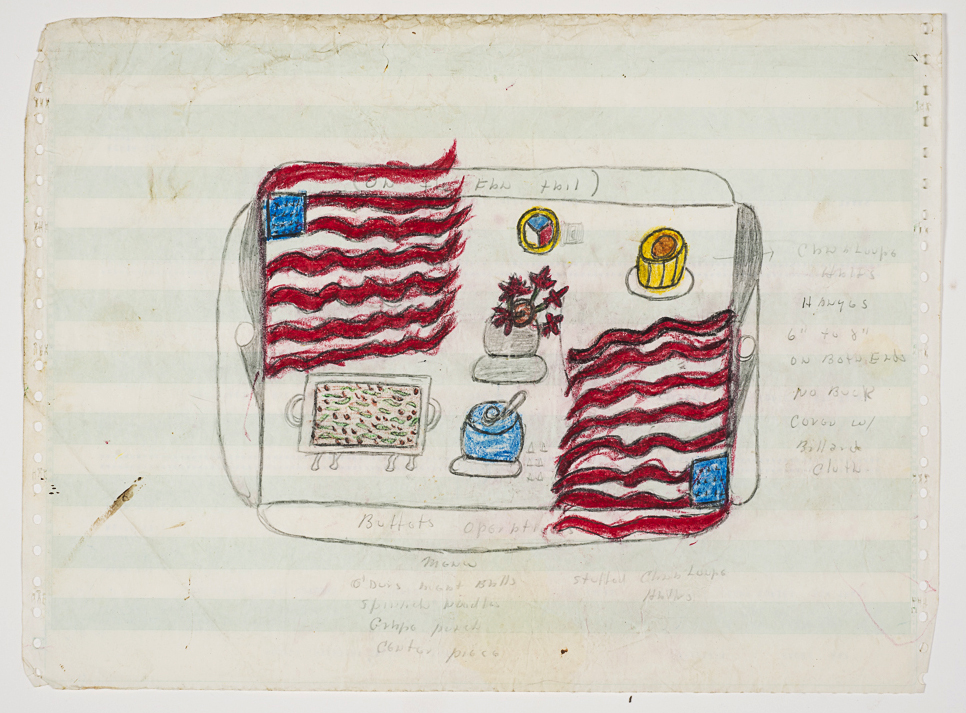

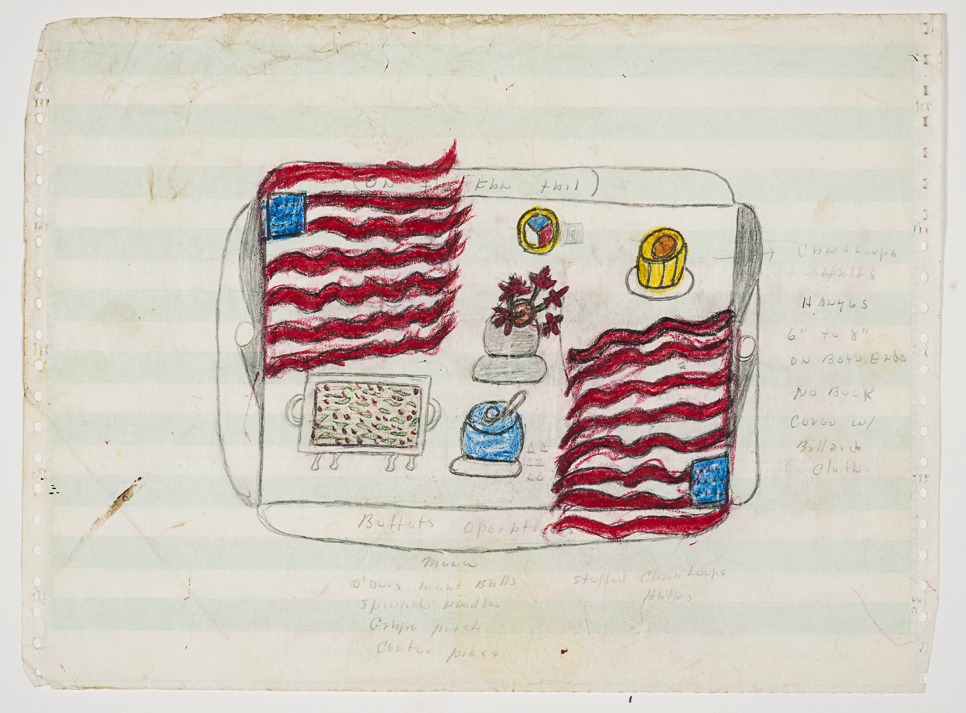

Image 20 – Stuffed Tomatoes Salads w/Russian Dressing It must have been a meal for officers because it includes “Baked Stuffed Potatoes with grated cheese” and “Fillet Mignon Steaks with mushrooms.”.Other drawings illustrate complete table settings. Image 21 is a drawing of a table draped with two American flags, set with a variety of dishes and a centerpiece of flowers. A title in the decorative border reads “On the Fan Tail” and “Buffet Operations.” The description below the drawing reads “Menu, O’Durs (sic) Meat Balls, Spinach Noodles, Grape Punch, Stuffed Cantaloupe Halves and a Center piece.” (If you google “On the Fan Tail” one of the first results is the site for the USS Intrepid Museum and a photo of a table on the rear deck of the ship with the caption: “Begin your event on Intrepid’s Fantail, located at the westernmost point of the ship. It is an ideal setting for outdoor cocktails before moving upstairs to the Great Hall for dinner.”)

Image 21 Another of Curtis’ decorative food illustrations is of a platter of Blue Fish (literally) “Baked Japan Style” (Image 22). This image is striking in its simplicity and bold colors.

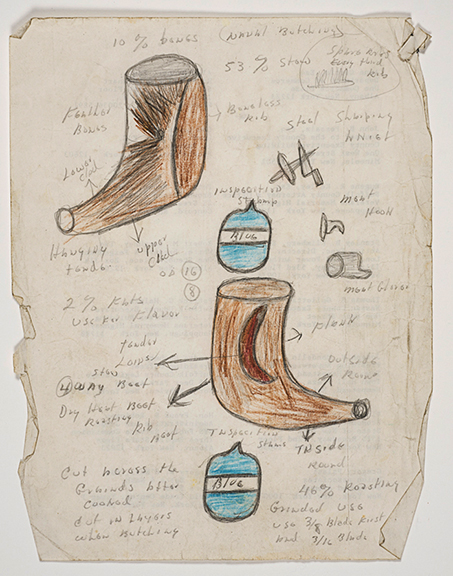

Image 22 – Baked Japan Style All three of these drawings (Images 19, 20 and 21) are done on the backs of found computer paper – the perforated edge, green and white striped kind that was common at that time..Another drawing reveals Fairley’s knowledge and experience in food preparation. Image 23 shows two colorful cuts of meat, along with detail sketches of blue government inspection stamps, cutting knives and a meat hook. Notes on the drawing offer helpful details like “Cut across the grain after cooked” and “2% fats – use for flavor.”

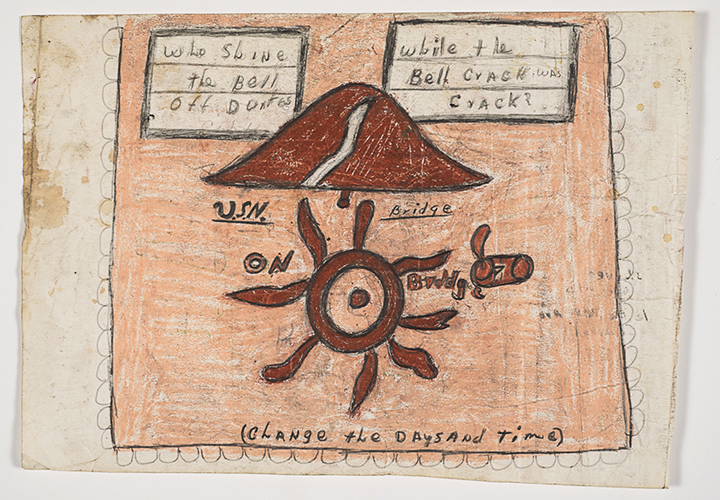

Image 23 Some of the most powerful of these ‘Everyday in the Navy’ images are of isolated objects or symbols that seem to have a special meaning to Curtis..One example is a drawing of a cracked ship’s bell positioned above a strange rendering of a ship’s wheel (Image 24). The two terracotta colored graphic shapes are isolated against a coral-colored background with a decorative border. A lever or control of some kind floats to the right of the wheel. The text on the images is carefully placed in outlined white boxes or arranged against the coral backdrop. The cryptic question posed within the text boxes reads: “Who shine the bell off duites (sic) – while the bell crack was crack?” Under the image of the bell is the label, “U.S.N. Bridge.” The words “ON – Bridge” are written next to the ship’s wheel. At the bottom of the page in parentheses is the inscription: “(Change the Days and Time).”

Image 24 – Change the Days and Time It’s hard not to conclude that this drawing is meant to convey a symbolic or allegorical meaning beyond the obvious words and images. I would love to hear possible interpretations from your readers, Kate.

Image 25

Image 26 – A Ship’s Compass

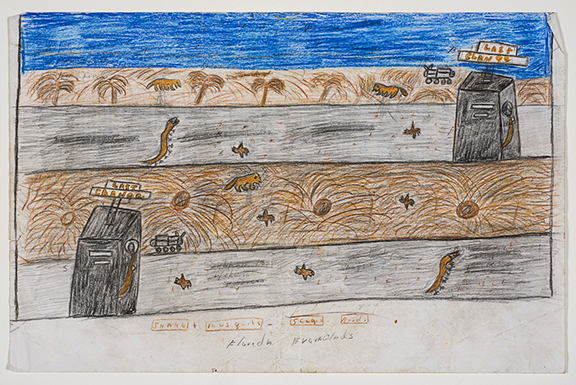

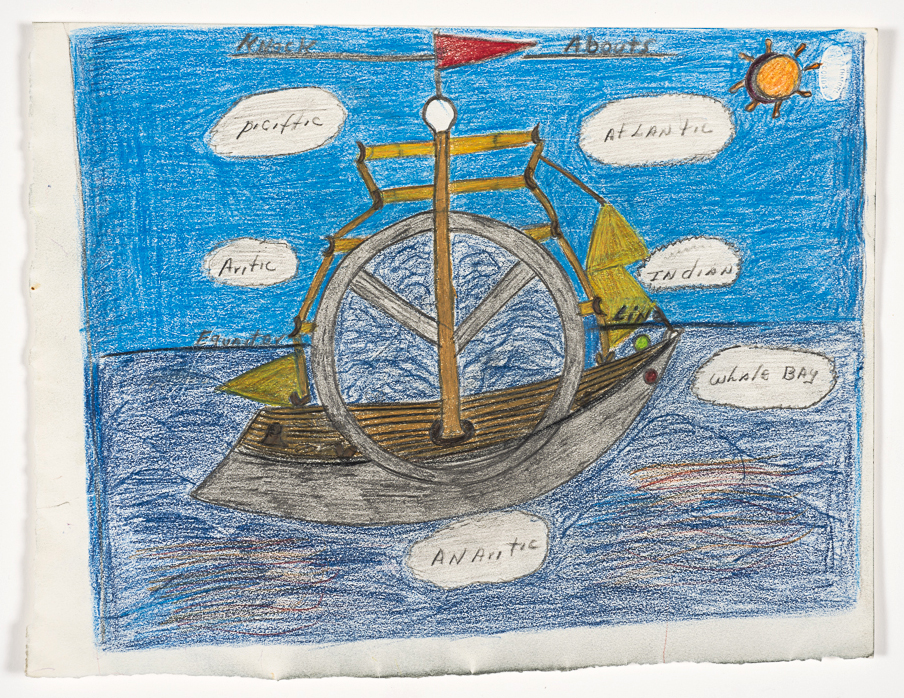

Image 27 – Engine Order Telegraph Image 25 shows a drawing of what I have interpreted to be either a ship’s compass (Image 26) or an ‘engine order telegraph’ (Image 27). Notes written around the image list various engine orders: “Full Speed Ahead, Full Speed Back” as well as names of oceans: “Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Artic.” Some of the notes give information about Curtis’ experiences: “The longest at sea – Six months, The shortest – 2 hours.” A descriptive/poetic note appears at the top of the drawing: “When ship gets lose (sic) what Happen – The Navigator shoot the moon or sun and fine (sic) his true courses.”.There are drawings that don’t seem to be directly connected to Curtis’ Navy life. Some of these are images of places where he may have lived or traveled. Two striking images from the travel drawings are of highways: the Santa Anna freeway (Image 28) and a highway through the Florida Everglades (Image 29). In both drawings Landry uses the full width of his paper so that the roadways stretch across the page and careen off either end.

Image 28 – St Anna Freeway

Image 29 – Florida Everglades The Santa Ana Freeway (Clayton labels it “St Anna Freeway”) in Fairley’s drawing is interrupted only by ‘trouble’ signs and light posts. In semi-circular landscaped areas on either side of the highway are a few lonely tulips or daffodils..The image of the Florida Everglades roadway is busy with all kinds of creatures crossing the lanes in the median and on the shoulder. Serpent shaped creatures with many legs (alligators?) wander across the roadway and a small creature like a miniature tank (armadillo?) appears on the grassy median and shoulder. Two ominous dark structures appear to be giant gas pumps loom over the lanes in either direction. The pumps have signs reading “Last Change.” I’m not sure if this was meant to be ‘Last Chance’ but either way I think a driver would get the point..Regarding the last part of your question, Kate, about whether Fairley recorded everything he saw or if he focused more on images that were important to his life, I think I would choose the latter as the motivation for his artwork. For instance there are very few drawings that depict the Manhattan streets where Curtis was living at the time that I knew him. The scenes and subjects of his artwork were largely drawn from his Navy life and must have represented his most memorable and meaningful life experiences. In depicting some of those experiences, as in the drawing of the cracked bell and the ship’s wheel, he sometimes seems to hint at deeper meanings and interpretations.. -

Introducing Curtis Fairley

In a new series on the blog, I will be asking George Lawrence about his collection of artwork created by a homeless U.S. Navy veteran whom he met whilst living and working in New York City. Lawrence has recently been delving deeper into the works he purchased from the artist in the late 1980’s, and into the life of the artist himself, by studying the biographical information included in the images and text of the drawings.

.

Lawrence has discovered the identity of the artist through public naval records but has not been able to locate or contact the man, who would be over 90 years old if he is still living..This first post will introduce Lawrence’s interactions with Fairley, with subsequent posts looking in more detail at the content and style of Fairley’s work.

1. Meeting Curtis Fairley

Kate Davey: Could you tell me about the first time you saw Curtis’ work? What was the initial impact it had on you?.George Lawrence: I first encountered Curtis Fairley around 1987 on the Lower East Side of New York City. I was working as a draftsman in a design office nearby. That area of the Bowery in the late 1980’s was a mix of neglected properties, Lower East Side art scene, and encroaching gentrification. Many of the local buildings were being bought and renovated by small businesses, artists and speculators. Nearby was a homeless shelter and a few blocks away was the rock club, CBGB’s..At the time I met him, Mr. Fairley was living at the shelter, but he spent his days writing and drawing, using the windshield or hood of a parked car as a drawing board. He worked with the regularity and commitment of a full-time employee. He was African-American, probably in his sixties and usually dressed in khaki pants and shirt and a knit cap.

1 Mr. Fairley used pencil, chalk, colored pencil and crayon on paper that he collected from the neighborhood trash. He often drew on both sides of his pages. Some of the drawings were done on the green and white striped computer paper that was then the standard. Other drawings were sketched on the backs of discarded business letters..I have always had a love for the work of folk artists and self-taught artists, so when I saw Mr. Fairley’s drawings I was fascinated by them and thought I recognized the raw work of a true ‘outsider artist,’ although I can’t recall if I knew that term at the time. I had taken some art classes and art history courses as part of my architectural degree and several of my friends were artists trying to find their place in the Lower East Side art scene. Mr. Fairley’s drawings had a quality of uninhibited originality that I didn’t see or feel in the more studied and self-conscious art I saw in the galleries. Coincidentally, I had recently been living in Brooklyn where my Puerto Rican landlord spent his spare time making art, using leftover house paint and scraps of Masonite. He would hang the paintings, which also looked like scenes from his childhood in Puerto Rico, in the hallways of the small apartment building. I admired in them the same vibrant, raw quality that I later saw in Mr. Fairley’s work..Over the course of a year or so I purchased about 50 drawings from Mr. Fairley and periodically I offered him paper and colored pencils, which he graciously accepted but did not seem to need. “I can find all the paper I need,” he told me. The drawings are illustrations of memories from his life. Common subjects include a variety of Navy ships, submarines, details of daily life, illustrated recipes, animals, exotic destinations and curious inventions. I was amazed by the intricacy of the illustrations and the detailed descriptive notes on many of the drawings.

2

3 I think that on some level I envied Mr. Fairley’s artistic spontaneity and his innate urge to draw whatever came into his mind. Of course I have no idea if that is how he experienced his life and I don’t assume to understand or diminish what he must have gone through, living on the street. Our conversations never progressed beyond a few halting sentences and I never felt comfortable enough to discuss with him how he had come to be homeless. There was, at the time, a movement to show the work of homeless artists at some of the local galleries, so I asked Mr. Fairley if he would be interested in showing his work. As I recall, he shook his head and said something like: “This is not art, these are just my memories.”

2. Fairley and the intermediate years

KD: When was the last time you can remember seeing Curtis in person?.GL: I don’t recall the last time I saw Mr. Fairley on the street outside my workplace. It would have been sometime in 1989. Over the course of a few days or weeks I noticed his absence. Someone told me that the nearby homeless shelter had been closed and was undergoing renovations. I assumed that the residents had moved to another shelter, but I never went so far as to investigate where in the city the other shelter might be, or what had become of Mr. Fairley..Around the same time that I lost track of Mr. Fairley, I had begun to make plans to leave New York. Much of my activity outside of work revolved around advocacy work with environmental groups in the city. A friend connected me with a group who were planning a coast to coast walk across the United States called the Global Walk for Livable World. I began to attend the local meetings and decided to participate in the walk as a way of leaving New York and discovering a new “path” for myself. So I quit my job, and in February of 1990 I flew to Los Angeles and, with about 100 other activists, began a nine-month walk back to New York. We walked mainly along state highways and camped in tents at sites ranging from college campuses to state parks to private farms. We coordinated as much as possible with local environmental groups along the way to hold public events highlighting the challenges to the environment specific to that community, along with promoting environmentally sustainable choices and lifestyles.

4 One of our stops along the way was Santa Fe, New Mexico. We were in Santa Fe for a few days for the celebration of “Earth Day 1990” and during the visit I decided that I would like to relocate there at the end of the walk. After the amazing experience of the 3,000 mile trek, I walked into New York City at the end of October 1990. Shortly after arriving, I packed up my belongings, including Curtis’ drawings, and moved to New Mexico..Upon my arrival in Santa Fe, I made a conscious choice to shift my career direction and began to promote myself as an architectural illustrator. In hindsight I wonder if my impressions of Curtis doing his detailed drawings may have had an influence on my decision. In 1996 I began work with a local exhibit design firm where I was able to employ my design skills, my illustration work, and my interest in the environment, for the design and construction of interpretive exhibits for state parks and visitor centers across the country.

5 Often, on meeting someone who I thought would be interested, I would share the folder of Curtis Fairley drawings. Many people over the years suggested that they would make an interesting exhibit or even a book, considering the connections to a variety of compelling issues, including the African American experience in the military, homelessness and of course, outsider art..In 1997 one of my friends in New York who had seen my collection called to say that he had seen Curtis’ name listed in an exhibition at an outsider art gallery in New York. The description, which had slightly misspelled his real name, described the exhibition as “Discovering the eccentric drawings of a lost New York Outsider Artist.” I tried at the time to make contact with the gallery but after leaving a few messages I failed to connect with anyone. Over the next few years I checked the internet periodically to see if Mr. Fairley’s name had appeared elsewhere. There are two other listings that I found, one for a 2011 Art Brut group show at Halle St. Pierre in Paris and another listing of a piece in the Smithsonian Art Library. This indicated to me that other people had been collecting Mr. Fairley’s work, probably in the same way that I had, by approaching him on the street..In 2013 I decided to put some real effort into uncovering more information about Mr. Fairley’s life. Many of the drawings are of Navy ships and scenes and have descriptive notes written across the pages and in the margins. I made notes from the drawings and sent the information to a website that offered to research and provide the public military records of armed forces veterans. For several months the researcher had no luck in locating Mr. Fairley’s name on any of the records from the ships I had listed. In the meantime I had been searching the military records available on Ancestry.com and I came across a very similar name on the “muster rolls” of a few of ships that Curtis had included in his drawings. I discovered that we had omitted one letter from the spelling of his (actual) last name. Once I was able to give the researcher the correct spelling, he was able to find and provide me with the military record through the Freedom of Information Act..I then went back to the web and, using the correct spelling of the name, I was able to discover one more reference. Apparently an artist who had a studio on the Lower East Side had purchased some drawings from Curtis and had included a reference and a print of one of the drawings in an article published in an online art magazine in January of 1987. In the article the writer describes Curtis just as I remember him, “drawing on cars.” “He has no studio or home but when it is sunny and he is drawing, there is nothing wrong in the world.”.Even with all the information I have discovered about Mr. Fairley, I have been unable to contact him or to determine if he is still living. If he is, he will be 91 years old in 2018.. -

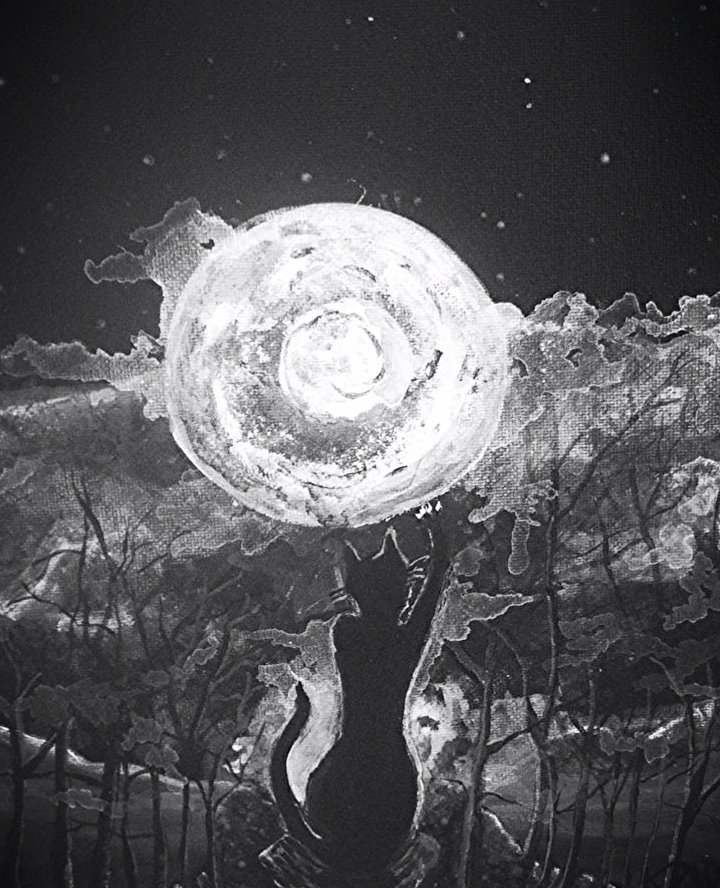

Artist Showcase: ColdMountainGypsy

This artist showcase features the work of ColdMountainGypsy whose folkloric work is inspired by poetry, stories and dreams. If you would like to see a showcase of your work here on kdoutsiderart.com, please email kdoutsiderart@yahoo.com with a few examples of your art.

Aurora When did your interest in art/creating begin?

I have loved art since I was able to grasp a crayon. My bedroom as a child was adorned with sketches of my beloved cat and dog. As a child my gifts to my family were always art. I often sent drawings to my grandparents when asked to write to them. I found art to be my letter, my thoughts, my little messages. Art even as a child gave me escapism, unbinding creativity and utter happiness. Art has always given me a voice, comfort, solace.

Eternity What is your starting point for each piece?

The starting points from my art are always different. My muses appear when they wish. Some are inspired through reading, some through nature, and some in dreams.

May the Forest be With You Who or what influences your work?

My influences are many, so in short: Pappa (GOD) my mother, my father, my husband, my brother, daughter, my fur babies, Cold Mountain, Forests, Poetry, Comics, the stars and the heavens, creatures great and small, angels, folk stories… even my stories or dreams. I write and dream lots.

Renegades What do you hope the viewer gets from your work?

What I hope the viewer gets from my work is wonder. There is no greater joy than hearing that someone loves your art. Every person that looks at a piece of art sees it in their own way. I have attached stories to some of the pieces to explain my muse or muses. I do feel that great and epic tales – be it folk or poetical or just sheer fantasy – should be shared. In my childhood I loved campfire stories and poetry. All of my works have stories, and I really hope they inspire happiness, wonder, a sense of magic, peace, contentment, folly, whimsy, brevity, and courage. My deepest hope is that someone out there decides to dive into art! My wish is that others realize how many of us are out there. Art is not just for those with a long listed pedigree. Art is for every caste. Art is a legacy for everyone to not only observe but partake in.

Marina What do you think about the term outsider art? Is there a term that you think works better?

I like the term Outsider Art because we are just that. If you are self-taught, have no sponsor, you have no displays in a public setting, you are not published in magazines, and if you don’t have art credentials then you very much are outside the renowned art hub. Self-taught artists are often not given chances for their art to even be shown. I know this because so far I have found only one open heart for me in my very artistic community. For me since I also paint always outside ‘en plein air’ the name suits me just fine. I often find I am more comfortable out in nature with my easel than in a crowd. For me, I never really quite fit in. For me, I have always been a bit of a black sheep and find inspiration in under dogs, in the misunderstood, the wanderers, and the dreamers. Simply put: ‘YOU ARE ENOUGH.’

I think everyone out there has art in them waiting to get out. The arts are not just paintings… The arts are so vast and are the last refuge for us all. People often forget the art of music, the art of dance, the art of poetry, the art of theatre, film… The arts are always dubbed in school as the ‘humanities.’ We live in a world with so many freedoms being taken away year by year that I hope all of the arts remain intact.

A Mewsing What are you working on at the moment?

I am working currently on Minnehaha, which has been inspired by my love of the epic book by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha.

Where do you see your work taking you in the future?

I really cannot predict where it will take me, I only know I will enjoy every minute of it.

-

Defining ‘Outsider’ Art..

Recently, I have found myself becoming more and more interested in the actual term ‘outsider’ art, and what it really means. Originally coined by Roger Cardinal as an English equivalent to Jean Dubuffet’s Art Brut (or ‘raw’ art), the term has grown to encapsulate a huge variety of works. There are many offshoots of the term, and it has become a sprawling label that many find difficult to define (including myself!)During the ‘golden age’ of ‘outsider’ art; which occurred between 1880 and 1930, the term was predominantly retrospective in that it defined the works of those who were now dead. It mainly included those who were incarcerated in some form or another, or those who suffered from severe social exclusion and the inability to access the commercial art market. Today, the term is more of an ‘umbrella’ for a variety of styles, works and artists. Under this umbrella we might see ‘Contemporary Folk Art’, ‘Marginal Art’, ‘Naïve Art’, ‘Self-Taught Art’ or ‘Visionary Art’. In this post, I hope to try and define some of these offshoots; if they are in fact definable in a black and white sense.

My understanding of the term ‘outsider’ art itself keeps changing; every time I read more about it – so I am sorry if this post seems confusing or the terms seem to overlap – I am trying to work out where I stand with regards to what the ‘label’ means to me.

Self-Taught Art:

Self-Taught Art is probably one of the more common offshoots of ‘outsider’ art that we see used. The term itself is quite self-explanatory; it describes those artists who have not received any formal professional art training. This would insinuate an exclusion (by choice or not) from the commercial or professional art market. But, to some extent, aren’t all artists self-taught? They all have their own unique style and choice of subject matter, despite where or how they receive their formal art training. To describe self-taught artists as ‘outside of the art historical canon’ seems somewhat of a generalisation. Just because an artist has not received professional art training does not mean to any extent that they are not aware of current art trends or the flow of art history.

Folk Art:

Folk Art, I think, is a little easier to define. It describes a more traditional, indigenous style that is characteristic of a particular culture. I think I have said it myself already here – it is a style. Self-Taught Art and ‘outsider’ art (however we choose to define it) do not describe a specific style. Some may disagree with me, but I think that ‘outsider’ art far from describes a style. It is not akin to, say, Expressionism or Impressionism or Pop Art. It has become more about labelling the artist, rather than the work itself. Back to Folk Art – Folk Art is in fact the perfect example of how these offshoots of ‘outsider’ art overlap and intermingle. Folk Art itself is often characterised by a unique naïve style (Naïve Art will be discussed later) – perhaps I am getting confused here – if Naïve Art is the style, does that mean that Folk Art is not a distinct style?

Marginal Art

Marginal Art describes the work of artists who are on the ‘margins’ of society for numerous reasons. But wait… Isn’t this one of the definitions of ‘outsider’ art? Some describe Marginal Art as that ‘grey’ area which sits right between ‘outsider’ art and the art of the mainstream commercial art world. So, for example, the scale would be as such: Mainstream Art – – – – Marginal Art – – – – Outsider Art?

Naïve Art

Naïve Art – I think – can be said to be a style. It is often produced by untrained artists (there’s the overlapping again), who depict realistic scenes combined with fantasy scenes in often bright, bold colours. Often defined by childlike simplicity with regards to the composition, subject matter or colour, present day Naïve Art is often created by those who have received formal art training – in fact, there are now even academies for Naïve Art. Does this mean it is no longer an offshoot of ‘outsider’ art?

Visionary Art

Visionary Art is another umbrella term – a term which can avoid the specifics and the confusion created by the label of ‘outsider’ art. It encompasses all of the above; Naïve Art, Folk Art etc. Visionary Environments, however, are slightly different (please refer to my previous blog post for more on Visionary Environments). These environments are created by intuitive artists and describe spaces that have been re-created in an extremely creative manner; often they are ‘fantasy worlds’ into which we can escape. It seems, however, almost ignorant to group these Visionary Environments under the umbrella of ‘outsider’ art – as often, the artists who create this amazing spaces are very much an integral part of their local community; they are by no means on the margins.

♦♦♦♦

I hope I have got you thinking about what the term ‘outsider’ art means to you – it is confusing, I know! The more I think about it, the more questions it raises for me. I am not sure it is really an appropriate label in terms of where the art of marginalised people stands today in the twenty-first century. Today, many an art work is undefinable – it doesn’t fit specifically into the art historical canon, but just putting artists into the ‘outsider’ art category seems to reduce the impact of the label itself. What I enjoy about ‘outsider’ art is the rawness of it; and the diversity – something which seems to be almost characteristic of such a broad title! Let me know what you think about ‘outsider’ art..