I am really pleased to be co-leading a new Research Group on behalf of Outside In for Tate and the Paul Mellon Centre’s British Art Network. The Research Groups typically run for one year, and offer an opportunity for an in depth focus on a particular part of British art history, providing new perspectives and new ways of engaging academically and curatorially with often overlooked areas of history. I am delighted to be co-leading this group with Jo Doll, an Outside In artist and Ambassador, and participant in Heritage Lottery Funded New Dialogues project.

(more…)Category: Outsider Art Curatorial Questions

-

In Focus: the Context of Outsider Art

Welcome to the final installment of ‘In Focus,’ a series of blog posts featuring question and answer sessions between me and PhD student Marion Scherr. In this last post, we’ll look at the term outsider art in an international context, and discuss the relationship between outsider art and the ‘traditional, mainstream’ art that is taught to college and university students.

Steve Murison, Unwitch My Heart with Bile and Rum Marion Scherr (MS): What are your experiences or thoughts on how ‘Outsider Art’ is dealt with on an international scale? I’m always wondering why the term is used predominantly – and with a few important exceptions – in the English-speaking West, and hasn’t caught on in other countries/languages to a certain extent.

Kate Davey (KD): This is a very interesting question, and something I am working with at the moment. I think, even within Europe, there is a lot of variation about how the term Outsider Art is used and the connotations that surround it. From my experience, there are parts of Europe that still very much use a medical model when discussing outsider artists and the work they create. I think this is probably because that is where the work originated in many parts of Europe – in psychiatric institutions – and it was found predominantly by doctors (e.g. Prinzhorn and Morganthaler).

I am not entirely sure why it seems so different in the UK – it is perhaps more to do with the history of mental health than the history of outsider art. Certainly there are very few organisations that focus on a medical model in the UK. Even Bethlem Gallery, which is attached to the Royal Bethlem Hospital, does not focus on a medical model. The artists are very much at the heart of what they do, and it is about being an artist rather than a patient.

In places like America, terms like self-taught or folk art are much more common than the term outsider art, and again, I think it is more a reflection on social history than art history, and I think this is the case for much of the world. In recent years, outsider art from Japan has become a big market, with much of the work that falls under this category being produced in Japan’s day centres. Again, social reasons rather than artistic – and I think this is probably the key to understanding why the term is so different across the world. I am not saying I agree with this idea, because it instantly takes the focus away from the art and puts it on society, politics and medicine (which we are trying to move away from in the outsider art world and focus purely on aesthetic), but it certainly seems to be true.

Manuel Lanca Bonifacio MS: I would be interested to hear more about your thoughts regarding the position of ‘Outsider Art’ in relation to “general” art history as taught in schools and universities. Do you think ‘Outsider Art’ should or can be included into the curriculum of art history? If so, how would you suggest it should be contextualized?

KD: I think it very much should be a part of taught art history at schools and universities. I was lucky enough to be taught about outsider art during my undergraduate degree in art history, but nonetheless it was taught in a separate module that was actually entitled ‘Psychoanalysis and Art.’ So, again, it was separated from the ‘art’ world, and was taught as more of a medical module. There are so many examples of key modern artists being influenced and inspired by the work of outsider artists, that if we do omit it from what we teach, we are at risk of missing out a huge and vitally important part of history.

In terms of contextualising outsider art, I think history can contextualise it perfectly well on its own. It was created at a certain point in time, for a certain reason – and much of it did intertwine with social, political and economic history. I wrote my undergraduate dissertation on the links between German Expressionism and Outsider Art, and this is a perfect example of a well-known (now, anyway) group of artists wanting to imitate the intuitive rawness evoked by outsider artists as a reaction to their own social and political context. There are many moments where outsider art dovetails with the ‘mainstream’ art world throughout art history, and I think to ignore this is to do a disservice to the greater picture of what ‘art’ is and what it can explain about society and humanity (now, and historically).

We hope you have enjoyed the In Focus series! If you have any comments or questions, please do post them below. Both Marion and I would love to hear your thoughts on any of the topics we’ve been discussing.

Featured Image by Matthew

-

In Focus: The Fascination with Outsider Art

Here is the third installment of the ‘In Focus’ series, which sees regular question and answer sessions between me and PhD student Marion Scherr. This post looks at the increasing fascination with outsider art, and the lack of the artist’s voice in exhibitions and publications.

Steve Murison, The One and Only Number One In Our Hearts Forever, Lemar Marion Scherr (MS): Although ‘Outsider Art’ is still a niche phenomenon, it seems to get more and more popular (considering the amount of exhibitions, specialist galleries, book publications etc.). Where do you think this increasing fascination with ‘Outsider Art’ comes from? Why do people seem to need this concept of the ‘Other’ or of the ‘Outsider’ in your opinion?

Kate Davey (KD): This is a really interesting question, and it’s something that I think I have figured out in some part based on my own experience of viewing outsider art. I think the ballooning in popularity of outsider art has in some respects had a lot to do with the art market and what sells. In recent years, the ‘otherness’ and ‘difference’ of outsider art has grown in popularity and galleries and dealers have managed to put a price on this.

If we move away from the art market – as I think this can sometimes muddy the water – in my opinion, the popularity of outsider art has come from people looking for something they can relate to on a more personal level. Certainly for me, fatigue with the ‘mainstream’ art world, and a sense that art was becoming more about money and sales and less about expressing an idea or a position, led me to become fascinated with outsider art. I think people (both art world and general public) can look at a piece of outsider art and feel like they are seeing a raw idea or expression. What I find with outsider art is that it gives me a physical reaction, which is something I rarely experience when looking at ‘mainstream’ art.

Increasingly, the world is becoming more capitalist, everything is based around making money and spending money, and I think there is a pull from outsider art because generally the artist has not made it to sell, or to increase their following, or to become famous. It is this naivety, and, ultimately, the feeling that we are looking at someone’s inner thoughts or inner voice, that is really magnetic. It is human nature to want to find out about people, to understand people who are the same as us, who are different to us, and I think outsider art really enables us to do this.

Particularly in the world we are living in today, outsider art can break down barriers between people from different backgrounds, from different countries, of different races and religion, and I think this is something people are actively searching for at the moment.

Jim Sanders MS: Considering the popularity of the genre ‘Outsider Art’, it still surprises me how little we actually hear from the artists themselves when we visit exhibitions or museums etc. In most cases there is a curator or collector talking “about” the artist and his/her work. Your blog seems to be one of the rare exceptions in the field, where artists are invited to share their version of the story and experience with the term. I’d be interested to find out more about your thoughts on this issue. Why is it that ‘Outsider Artists’ are normally left out of the dialogue?

KD: Absolutely, I completely agree with you on this one. I think it’s definitely getting better, and there are certainly studios, projects and organisations that are working on rectifying this issue in the outsider art world by putting the artist’s voice at the heart of their work.

Personally, I find it incredibly important to include the voice of artists, not just in exhibitions and publications, but also in defining the term and discussing its development. I think the idea of curators and art historians defining what a movement is, who can be involved, and what is written about it is something that dates back a long way. I think the nature of outsider art and the artists the term can encompass is one of the stumbling blocks curators in this area have to learn to work with. Artists can be non-verbal; artists might not consider what they create to be art; they might not know how to talk about it. I think curators can try to fill this gap, when really, we should constantly be checking ourselves, making sure we’re working with artists at every stage of the process, enabling them to communicate about their work in whatever way that might be (video, words, poetry, other visual tools). And if they aren’t able to communicate about it, then realising that that is OK too. The work will speak for itself.

Because a lot of outsider artists have not travelled the traditional route through art school, they probably won’t have learnt about the art market and how it works along the way. They are creating as a form of catharsis, it can be an urge, or an innate part of their survival. It can be easy for curators who see the incredible output of outsider artists to take advantage, and I think this is something that has tainted the outsider art world. I am a strong believer in co-production, and as curators and promoters of outsider art we also have a social responsibility to not be another ‘institution’ that labels people, that puts words in their mouths, or groups people or artists in a way they are not comfortable with. It is difficult, and it is a learning process, but we need to overcome the historical idea that curators are the ‘expert’ or the ‘trend-setters.’

There is so much to be gained from working with artists directly, learning about their processes, how they work, what inspires them, and it is such a shame that this can so often be lost in the way work is displayed. Particularly with contemporary outsider art (where the artists are still living!), we have such a great opportunity to share the voices and insights of such a huge range of interesting people. It can be a great way not to just learn about art, but to learn about difference and similarity – and human nature!

Featured Image: Mitsi B, Time to Go

-

In Focus: Exhibiting Outsider Art

Welcome to the second installment of ‘In Focus,’ a series of blog posts that see a question and answer session taking place between me and PhD student Marion Scherr. This post focuses on the implications of the term ‘outsider art’ for the artists it describes, and considerations when exhibiting works of outsider art.

Joanna Simpson, Good Luck Gum Nut Folk Marion Scherr (MS): You know many artists yourself and seem to have talked quite a bit with them about the term. Could you give a brief overview of the different opinions and viewpoints artists have about the term? What are the pros and cons people mention when speaking to you about the term ‘Outsider Art’?

Kate Davey (KD): I’ve generally found that artists don’t feel as strongly about the term as academics and curators do, which I find interesting. I’ve had mixed responses, from people who are really pleased to have a found a term (that comes with its own artistic community) that they feel an affinity with. Others have expressed feelings about it being quite limiting, particularly in terms of what kind of shows they can enter or exhibit in, and how they are viewed as an artist.

Interestingly, a couple of years ago I did a blog post focusing on artists’ responses to the term. From this, you can see that a fair few of the artists note that in the term outsider art they have found a ‘movement’ that they feel they themselves and their work can belong in – and belong in successfully. I think there’s something about artists who might see themselves as ‘outsider artists’ finding a community of other artists who view themselves and their work in this way. I find this is quite different to the mainstream art world which can be quite saturated with competition. Certainly I’ve found much more comradery amongst outsider artists, which is always really good to see.

I think I might have mentioned this in a previous answer, but I think that artists who see themselves as ‘outsider’ artists are able to access more support with their professional development and their artistic career through organisations specifically set up to support and promote artists doing this kind of work, which is so important.

Julia Clark, Owl MS: Do you think the way in which a work of art is perceived changes, if the audience is told it has been produced by an ‘Outsider’? What is the feedback of gallery/museum visitors like in this regard in your experience?

KD: In my experience, there have been mixed reviews, but generally people are very open to experiencing new kinds of art, and particularly art that might be different to the work they normally view. It’s not to everyone’s taste, and I think this is sometimes where a bit of context can be really useful. I have had a couple of experiences in the past where exhibition-goers have maybe asked ‘what’s wrong with’ one of the artists whose work is on display, but I generally take this as an interest or curiosity in the work and the person who made it – and this is when I’ll talk about outsider art and what it means today.

I think in recent years the market and for and opinion of outsider art has come on leaps and bounds – certainly in the U.K. where we’ve had big exhibitions at the Wellcome Collection and the Hayward Gallery. The main thing, I think, is to display work by ‘outsider artists’ just as you would the work of a ‘mainstream’ artist, so the public see it as valid art and are able to appreciate it for its aesthetic qualities.

I’ve had a few really positive experiences where people weren’t expecting to come across ‘outsider’ art at a gallery or museum, but they have gone away feeling like the work was the most powerful work they saw during their visit.

I think as taste makers, curators and galleries have a role to play here. As long as they are showing ‘outsider’ work (and showing it well) then art audiences (and the more general public) will come to see this work as valid – and, most importantly, as art.

MS: In one of your blog posts you mention that the show ‘Jazz Up Your Lizard’ has changed your mind about curating ‘Outsider Art’. Rather than presenting it in a ‘white cube’ you speak about turning this approach round and “shaping the place to fit the work” and/or finding a space, that works well with particular artworks. What are your opinions on this issue now? What do you normally look out for and what elements do you consider, when you think about the place and setting of a show?

KD: The Jazz Up Your Lizard show was a real turning point for me. As I’ve written about before, I was adamant that outsider art be shown the same way as its ‘mainstream’ parallel. However, this show was a bit different, as I was working very closely with the artist throughout – an artist I have known and admired for a long time. There were also some practical issues involved – the exhibition space had been painted black, and the curator I was working with on the show really liked the colour (and so did I!). The exhibiting artist’s work is very bright, but macabre in content. I think the black just really brought out the colours, as well as the darker side of the works – that on first inspection can sometimes seem fairly jolly.

When curating exhibitions in future, I’d really like to take the lessons I learnt from this show on board. Things I would now consider include what it is we want to pull from the work – what is the essence of it? What might people get from it and how can we help this along? I’ll always work closely with the artist, where possible, as they are the best interpreter of the work. When curating, I really like to think about audiences who might not ‘naturally’ consider visiting an art exhibition – or more specifically an outsider art exhibition. Anything that helps them experience this work is absolutely vital. This includes colour, space, accessibility, accompanying text, events etc. So these are now all things I consider in great detail.

Featured Image: Don’t Look Back in Anger by a Koestler Trust entrant

-

In Focus: The Question of Outsider Art

Over the past six months or so, I have been contributing to a project by PhD student Marion Scherr. Marion initially got in touch because she is currently completing her PhD thesis at the University of Oldenburg, Germany (School of Linguistics and Cultural Studies), focusing on the personal experiences, opinions and thoughts of artists who have been labelled or choose to label themselves as ‘Outsider Artists.’ She is comparing and contrasting the artists’ personal experiences with representations in academic and media discourses in the UK.

Since summer 2017, Marion and I have been in a game of email ping pong, sending emails to and fro about the nature of outsider art, what it means for curators and academics, and ultimately, what it means for the artists themselves. After speaking to Marion, I thought it would be interesting to relay some of the conversations we’ve been having. The series has four installments, of which I will post one per month for the next four months. Both Marion and I would love to hear your comments on any of the questions or answers, so please do leave them below. Keep reading for the first question!

Mitsi B, Always Marion Scherr (MS): When and in what context did you come across the term ‘Outsider Art’ for the first time, and how have your opinions on the term changed since then?

Kate Davey (KD): I first came across the term outsider art in 2008 when I was studying for my undergraduate degree in Art History. It was introduced to us during a module on psychoanalysis and art, which predominantly focused on sublimation and perversion in art. I remember seeing images of work by Richard Dadd during the lecture, and it was the first time a piece of work has ever truly made me feel something. It was then that I decided I would focus my attention on this interesting (and to me at that point, completely unknown) area of work. I visited the Bethlem Museum archives to see Dadd’s work in the flesh, which was a fantastic experience.

I focused my BA Hons dissertation on outsider art and then went on to do an MA in Art History and Museum Curating, this time focusing more specifically on curating exhibitions of outsider art. At this stage, I was somewhat accepting of the term – it described an area of work that I needed to describe in my essays and using that term made it easier. I did a lot of reading around the subject, both for and outside of my studies, and I was looking for an outlet to share my thoughts and discoveries – which is when I started this blog.

It was a combination of this research and starting work for a couple of organisations that supported marginalised artists that encouraged me to start questioning the term. Until that point, it had been a given, and particularly as an undergraduate student, it’s difficult to question these things. My blog became somewhere where I could air my thoughts freely, sometimes heading off on tangents, but always feeling better once I’d written it down.

I started to become dubious of the term, wondering why – unlike other movements in art history – this term described the person creating the work rather than the work itself. I wrote many posts about how the ultimate aim is the complete elimination of the term ‘outsider art’ and the unconditional welcoming of ‘outsider artists’ into the mainstream canon. My views have changed many times over the years, and at one point I welcomed the term again, wanting artists who might be grouped under that term to ‘take it back’, in a similar way to what happened during the disability arts movement. Over the years I have also had the opportunity to speak to many people about the issue, including many artists, and have found that definitions and ideas about the term are varied and diverse.

A couple of years ago I decided to do a call out on the blog for artists to submit their visual response to the term outsider art, and to give an alternative term that they might prefer to use. This was very enlightening – most of the artists did still want a term, whether that was ‘outsider art’ or not, and many of them were in fact happy with the term. I have done a lot of research on taxonomy and categorisation, and humans innately like to group things together. I think for this reason, there does need to be a term, but there is still a long way to go in unpicking what it really means, and ultimately (and most importantly), unpicking what it means for the artists it describes. Does it condemn them to work in the ghettos of the art world, never really being a true part of the art historical canon? Does ridding ourselves of the term also mean we will rid ourselves of all of the wonderful organisations who are supporting artists who face barriers to the mainstream art world?

As you can see, I am still not at a final decision, and I don’t know if I ever will be – and in some ways, I hope to never not be. This is a topic that continues to fascinate me, and I will keep exploring it.

Manuel Lanca Bonifacio MS: You have been involved in putting together exhibitions yourself – how do you personally define the term? And how would you explain it to a visitor who isn’t familiar with the term at all?

KD: I think over the years I have become much more flexible about who might be considered an outsider artist, and generally (for my blog) I will leave it open to the artist to decide if that’s something they would like to be associated with. In terms of the exhibitions I have curated, I have tried to convey that the artists I consider to fall under this category create because they have to, not to sell the work, not to gain any fame from the work etc. My hope is to inform the public that anyone can be an artist – anyone can create, and anyone should feel like they are able to create. It’s always a bit of a win if someone comes along to the exhibition feeling inspired to go home and make or create something themselves.

I do also give people information on the history of the term – objectively – so that the public are able to come to their own conclusions about what might be considered outsider art (and it generally helps people to see where the work has come from and the context that this sort of work sits in more widely).

If I were describing the term to someone who didn’t know about it, I would give them Roger Cardinal’s definition as a starting point, but would hope to convey to them that I consider it to be a term that encompasses people who haven’t necessarily taken the ‘traditional’ route to become an artist. It’s about unfettered creativity and a need to produce something – which is actually what innately makes us all human. I find I know people who don’t consider themselves ‘art’ people, but once they see a work of ‘outsider art’ they find they can relate to it more easily than a piece that has developed out of an art school or the art historical canon.

So I guess to sum up, I haven’t got an ‘elevator pitch’ for what I think outsider art is now, but I’m very open to (and thoroughly enjoy!) discussions with a wide range of people about this area of work. I think it’s an open conversation and everyone who is working in this area – curators, researchers, directors, and artists – should aim to engage with people about the subject. It’s such a fluid thing, and it’s a ‘type’ of art that has been so fluid and depends so heavily on people, that it doesn’t feel right to have a strict paragraph of text to define it.

Featured image by Alan Doyle

-

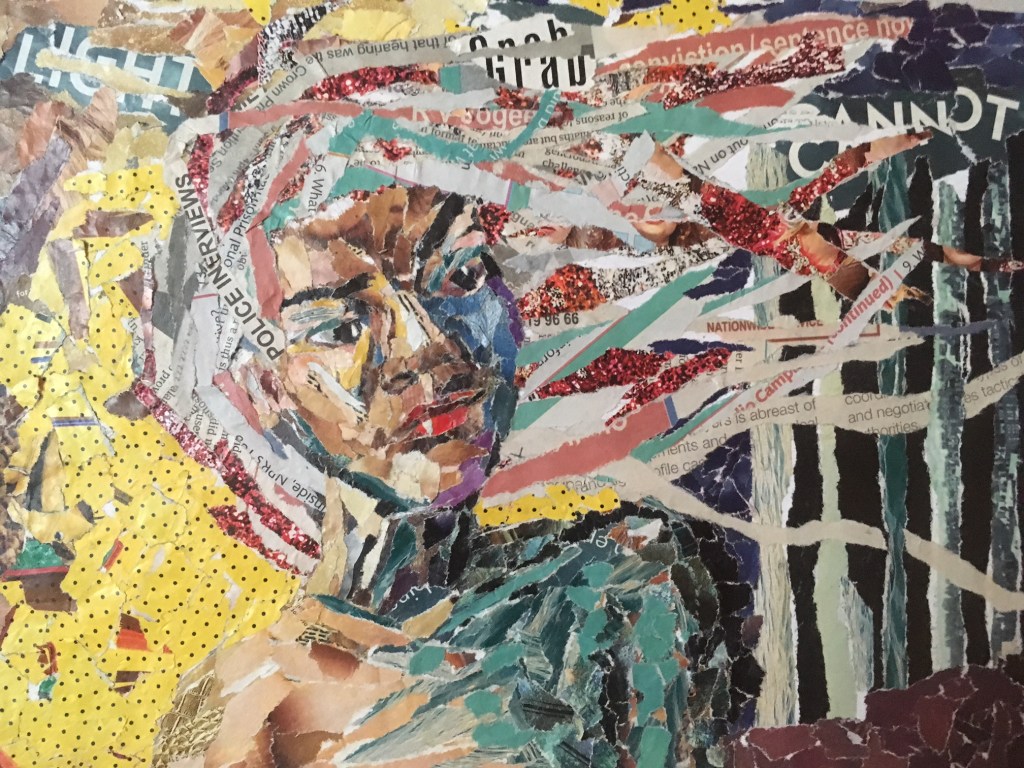

NEW Online Exhibition: Redefining Outsider Art

A few months back, you may have seen my call out for artists to submit work on the theme of ‘outsider art’ for an online exhibition. Well, we had some great, diverse submissions, and the exhibition is now ready.

Click here to visit the online exhibition

If you are a regular reader of kdoutsiderart.com you will have noticed a focus on the terminology itself and how this might impact on the artists it represents. Throughout history, the different language used to describe what we call outsider art has usually been decided by someone who is not themselves an ‘outsider artist.’

For this online exhibition, I wanted to bring in the perspective of artists who are regularly ‘labelled’ by the term to bring some balance to the continuing conversation.

As human beings, I think it’s incredibly difficult to not label things. We do it all the time – using our own memory and experience, we group things with other similar things (objects, people, places) in a bid to make sense of them. It has been the same throughout the history of art: work created with quick, expressive brushstrokes towards the latter part of the 19th century was labelled ‘Impressionism,’ and Dali, Magritte and others who produced work from their unconscious were named ‘Surrealists.’ So, it is not unique to have a name for a group of art or artists. However, what’s puzzling about the term outsider art is that it doesn’t describe a specific artistic style; rather, it describes the person who created the work.

This exhibition aims to shine a light on the views of artists who align themselves – or who have been aligned – with the term ‘outsider art.’ The callout received mixed responses to the question: what does outsider art mean to you? From experience, there seems to be a split between artists who are very happy to be included under the ‘outsider art’ umbrella, and those who would rather not be. It has been great hearing artists’ alternative titles; I’ve heard things like ‘Independent Art,’ ‘Dark Surrealist Art,’ ‘Symbolic Automatism,’ ‘Nomadic Art.’

My hope is that this online exhibition will be a rich addition to the continuing conversation around the term outsider art.

Featured image: Ofir Hirsch, La Hechicera Enamorada Terrenero

-

Life is your very own canvas

‘Life is Your Very Own Canvas’ is an exhibition showcasing expressive art created by individuals somewhere along the road to recovery. The exhibition has been organised by Penumbra Art; a new collective of artists who are exploring the creative path together in a supportive, encouraging and safe environment. The exhibition is happening from 27 May – 3 June 2016 at Seventeen in Aberdeen.

3D dragon sculptures, high quality black and white street photography and a time travelling comic strip are but a few of the eclectic works on show.

Mid-exhibition, on 31 May, there will be a showcase event where I will be talking about outsider art: then and now, and Best Girl Athlete will be performing.

The exhibition is open:

Friday 27 May, 10am – 5pm

Saturday 28 May, 10am – 4pm

Tuesday 31 May, 10am – 5pm and evening showcase 7pm – 9pm

Wednesday 1 June, 1.30pm – 5pm

Thursday 2 June, 10am – 5pm

Friday 3 June, 10am – 5pmVenue: 17 Belmont Street, Abderdeen, AB10 1JR

For more information, click here.

-

The Story of Art: our collective history

I feel like I haven’t written a longer piece on outsider art and its accompanying tensions in a long time. A visit to the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester – part of a team day out in my final weeks working for Outside In – took me back four years to the research I was conducting into displaying outsider art. The Whitworth, structurally both modern and beautiful, has been home to the Musgrave Kinley Outsider Art Collection now for several years. The collection is one of the formative and most important Outsider Art collections in the world, and includes works by prominent figures such as Aloise Corbaz, Johann Hauser and Lee Godie.

Johann Hauser, Nackte Frau mir Hut, Art Brut Center Gugging, Maria Gugging Currently at the Whitworth, an exhibition focusing on portraits expertly showcases a huge number of works from the gallery’s collections – including the Musgrave Kinley Outsider Art Collection. It was a privilege to see works by the likes of Ben Wilson, Hauser, and Corbaz alongside great British masters such as Francis Bacon, Sir Stanley Spencer and Leon Underwood. There is no division in the exhibition between work by tutored, mainstream artists, and the equally aesthetically brilliant works by so-called ‘outsider’ artists.

Curator Bryony Bond says: “Many works predate the gallery’s formation by hundreds of years, others were made on different continents, and many more were made without the expectation of being shown in a gallery at all. Together, however, these individual works of art, each made in different circumstances, shape the collection, and give the Whitworth its unique personality.”

Johann Hauser, Frau mit Fahne, Art Brut Center Gugging, Maria Gugging Back in 2013, I wrote a blog on the relationship between ‘outsider’ art and the ‘traditional’ history of modern art, in which I touched upon the abandonment of ‘outsider’ art within most art history curriculums. So often excluded from the history (and story) of art, ‘outsider’ artists have been wholly welcomed into the Whitworth exhibition, helping to illustrate the history of a prestigious art gallery, its donors and collectors. This highlighted for me the importance of including such works in telling the story: whether that’s a story about collections and collectors, or whether it’s the story of art – and, to go one step further, the story of humanity more generally.

Let’s take Hauser as an example. Born in 1926 in Slovakia, Hauser was admitted to a psychiatric institution at the young age of 17. He was transferred to another hospital near Vienna in the late 1940s, where he remained for the rest of his life. Here, he joined the Haus der Künstler (House of Artists), where his doctor – the lauded Leo Navratil – encouraged him to start drawing. His work took inspiration from popular culture: portraits of film stars, current events and photos of war machines.

Aloise Corbaz Does erasing works by people like Hauser erase people like Hauser? Surely if we are telling the full unadulterated story of art (and humanity), these are important chapters.

Corbaz was born in Switzerland in 1886. At the age of 32, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. It was after this admission that she began to experiment with creative writing and drawing. At first, she kept her creations on scrap-paper secret – whether for reasons of fear or privacy, but after a while she was allowed to use larger sheets of paper as well as crayons and coloured pencils. Corbaz is now one of the most celebrated ‘outsider’ artists in history. If we erase her work, are we erasing her story – are we erasing her as a person?

Aloise Corbaz In this respect, the Whitworth is leading the way (certainly in the UK anyway). By integrating work by the renowned British modern greats and the work of artists like Hauser and Corbaz, they are accepting – and celebrating – the great breadth and variety of people who are and were a part of the story of human history. Their work is equally as – if not more – important in shedding light on the diverse experiences of human beings. Art is a great way to share the truths and tribulations of being human and provides a visual tool to help reduce stigma surrounding fundamental issues like mental health and disability. We must remember to include the diverse stories of people from all walks of life to ensure our collective human story is varied and interesting, but above all, to ensure that it is truthful.

‘Portraits’ continues at the Whitworth Gallery, Manchester, until 23 October 2016.

Click here to find out more about the show