A new qualitative study, commissioned by Axisweb, focuses on how artists receive validation for their work outside of the ‘traditional’ gallery setting. I think this is particularly poignant for all artists including self-taught artists and those who are not or do not wish to be aligned with the gallery agenda.

The researchers working on the study interviewed producers, commissioners and artists, seeking views on how different people receive validation for their creative endeavours, and whether the existing structures have – or had – an impact on how they seek or receive validation. The main findings are outlined below in a brief summary:

“The findings reveal an ad-hoc and informal approach to validation in the field. The commissioners, producers and artists interviewed agreed that the responsibility for seeking and maintaining validation falls largely to artists. While this was accepted as the norm, the majority of artists perceive a lack of support structures to help those operating outside the gallery system achieve and maintain external validation.”

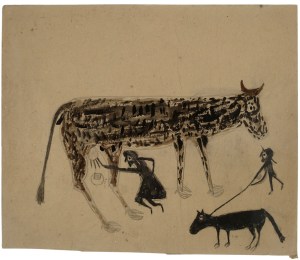

There a few interesting things to take away from this in terms of thinking about validation and how artists receive it, seek it, and ultimately whether they need it at all. Traditionally, one of the key characteristics of the ‘outsider artist’ is their ability to create for themselves; because they need to, because they want to, rather than creating a saleable object or a commodity item. So where do they get their validation from? It may even be more difficult for them to find validation, with many not having not had the ‘rite of passage’ that is art school.

Does validation come with a price tag? Is work of a higher monetary value confirmation of a valid and successful artist? It, thankfully, seems not. In the report, artist Joshua Sofaer is quoted as saying: “Amongst me and my peers, we might consider somebody that goes towards gallery representation, starts making discrete objects, as somebody who has sold out.” Although he does go on to say that “other people might think they’ve arrived.” Additionally, many respondents felt that gallery backing was “more meaningful to others than to the artists themselves,” with many claiming that “the commercial numbers-led art world was potentially detrimental to the development of a high quality and original artistic practice.”

It is refreshing to see that although gallery representation is often sought after, many of the respondents did not “view gallery validation as a good fit for their values and practices.” Increasingly, it is perhaps true to say that artists are needing gallery representation less and less; for many, it is no longer the gold at the end of the rainbow. With the burgeoning use of the internet for self-promotion, artists can market and sell their work without the middle man, creating and selling on their own terms. This does, however, require the artist to have some knowledge of utilising internet marketing tools, a hurdle to overcome if you’re working towards self-representation.

Although it is comforting to see the findings highlight the differing value systems amongst artists “from those they see underpinning mainstream galleries and the work shown there,” to me it seems there is still some way to go. Take, for example, the difference in status between community and educational art and a ‘national gallery commission,’ the former is still looked upon as lesser form of art than the latter, despite the inclusion of community and learning programmes in most major national and regional art galleries and museums. Worryingly, artist Ania Bas acknowledged that “A lot of artists that I know… don’t talk about any work that they would do for the education department… In fear that this would mean that they would never… be invited to do a show in the gallery.”

So it seems from the report that whether validation is based on monetary value, visibility or gallery representation, there still seems to be an apparent separation, in terms of both support and funding, between work traditionally included in the ‘gallery agenda’ and art produced by socially engaged artists or those working outside of the mainstream. How do we overcome this? There certainly needs to be some sort of reform in terms of what high quality, valid art looks like, and in terms of who gets to decide. Rather than a sellable end item, perhaps a focus on process and idea needs to come to the fore. After all, if the only art seen as valid is the art that ‘sells’ and the only successful artists are those with a nose for business, we will continue to miss out on so much rich, unique and meaningful creativity.

The concluding paragraph of the Axisweb report mentions that to encourage a rethinking of current validation systems, any new provision should be artist-led, because “without this, artists could be disenfranchised through external values being imposed on them in ‘top down’ regulatory ways. This in turn might undermine the existing quality and nature of artists’ work occurring within the broad category of socially engaged or non-gallery art.”

I’d be interested to know what validation looks like to you. Does it come from the art world, does it come from yourself, and how do you go about finding it? Please post any responses you might have in the comments below – thank you!

Axisweb commissioned Validation beyond the gallery (June 2015) from Manchester School of Art, focusing on artists working outside of the gallery system. The report was written by Amanda Ravetz and Lucy Wright. You can read the full report by clicking here.

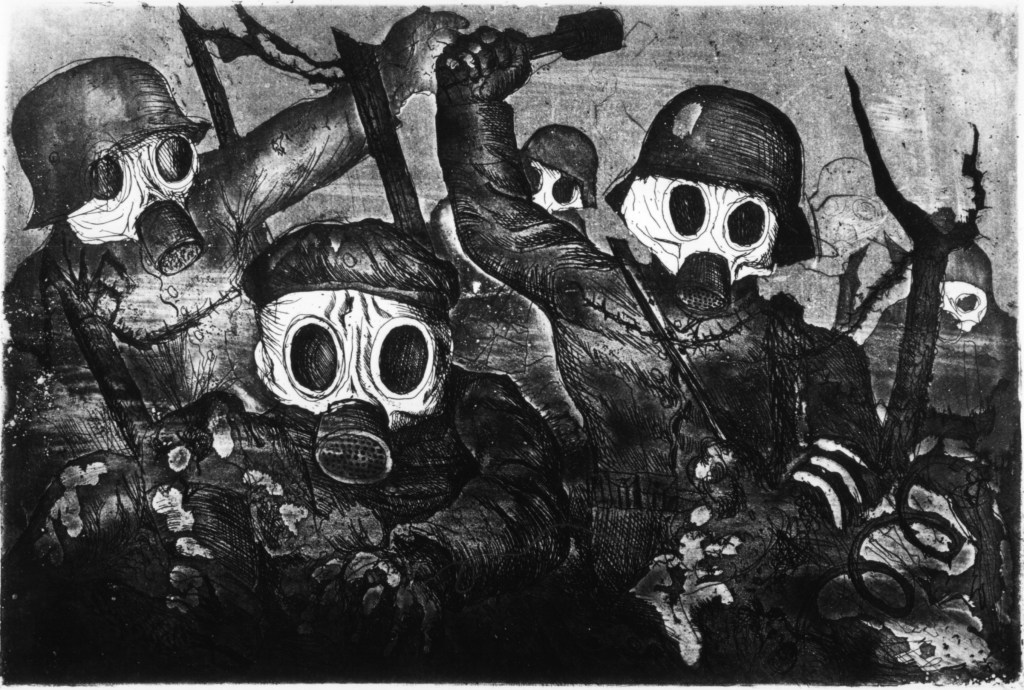

![Otto Dix, Schädel (Skull), 1924 [Courtesy of: www.deborahfeller.com]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/the-skull-1924.jpg?w=766&h=1024)

![Otto Dix, Gastpte - Templeux-la-Fosse, August 1916 (Gas Victims - Templeux-la-Fosse, August 1916), 1924 [Courtesy of: www.port-magazine.com]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/gas-victims.jpg?w=640&h=460)