On Sunday 22nd April, BBC Radio 3 aired a programme by writer A. L. Kennedy on the supposed links between art and madness. In this post, I want to briefly summarise Kennedy’s views within the programme and discuss some of the questions she raises.

“Losing one’s mind is a negative, terrifying experience, freeing it can be nerve-wracking too, but also exhilarating, beautiful and eloquent – for everyone.”

Kennedy begins by noting that we often link art and madness – we don’t link, for example, art and sport, or art and banking. As a female writer, she claims that ‘mad dead Sylvia Plath’ and ‘mad dead Virginia Woolf’ are her role models. As humans, we are ‘obsessed’ by ‘mad, dead’ icons – and, to some extent, this is a myth that can trivialise madness and marginalise art.

But, what constitutes madness? Dorothy Rowe, Psychologist and writer, claims that even those with a ‘healthy mind’ cannot directly see reality. It is something which is impossible for us as human beings. We can only believe the ideas our brain gives us. Reality is in fact, she claims, a story we tell ourselves; how then, do we know what is, really is?

Further into the programme, Kennedy takes us as the listener on a journey to a hotel. She is suffering from dizziness, nausea and anxiety – something, she claims, that might suggest to the hotel receptionist that she is ‘stoned’. She explains that that wants to tell the receptionist that she is a professional – a writer, but suddenly, she is embarrassed and ashamed of her profession. To claim she is a writer, in this country in particular, will only confirm beliefs of extremity, eccentricity and madness. She asks, rather pivotally, has a long term exposure to her art harmed her?

Lisa Appignanesi, a British writer, states that there are many people self-diagnosed and professionally diagnosed with a mental illness who do not ‘create’ in some sense – therefore, there cannot be a direct link between art and ‘madness’. Why is it then, that we insist that all artists experience ‘bad times’?

Shakespeare’s portrayals of madness are interesting to note. For example, Hamlet is the “sanest guy” acting out in an insane situation and Lady MacBeth is maddened by destruction not construction – or creation. Shakespeare, then, could be said to focus on the insanity of the world, rather than the insanity of the artist.

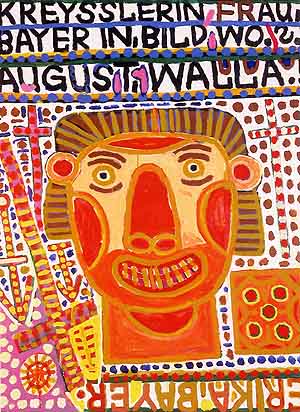

The individual, it is claimed, is most defined as individual in extreme states. Madness, then, is an extreme expression of individuality.

The modern era of art embraced madness; something which could be portrayed as somewhat insulting to those who wake up every morning with no choice. Involuntary mental distress means that our guesses are wrong; we become anxious as a result of this, and then fearful – “we feel ourselves falling apart.” Often, literature on the connection between art and madness beautifies the experience of mentall illness. Psychiatrist R. D Laing once said that Schizophrenia was a type of poetry.

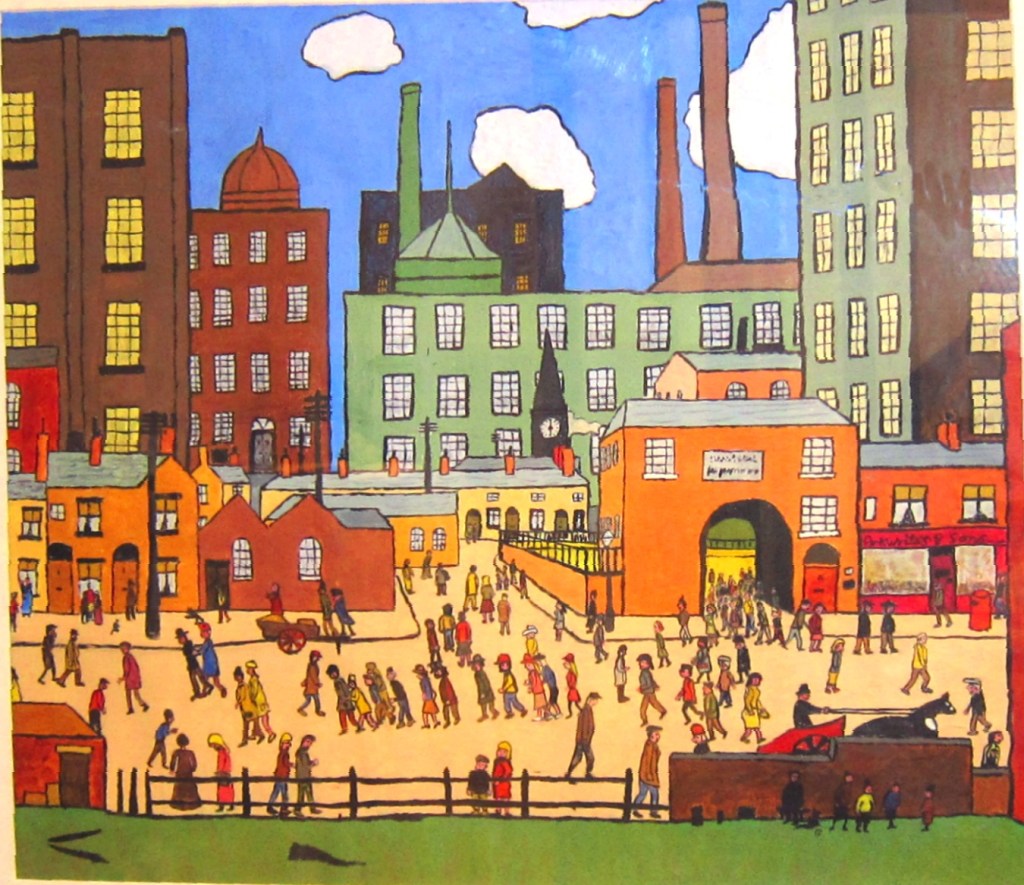

Kennedy looks at the work of William Kurelek. She asks if we choose to associated madness with artso that we don’t have to associate it with ourselves.

The connection that is usually made is one which states that the ‘mad’ artist creates more, or perhaps only creates at times when they are experiencing mental distress. This however, is evidentally not the case. Van Gogh, for example, could not paint during times of deep distress and Virginia Woolf would often only experience breakdowns after she had written.

Being an artist can often create another identity for someone who is suffering from a mental illness. They become an ‘artist’ as opposed to an ‘unwell person’. The creation of art can be therapeutic – not, as Kennedy claims, in the sense of Art Therapy, but in terms of the fact that producing art for many people makes them feel better. Does this not then undermine the myth if art is in fact a cure for madness?

Being an artist in itself can create turmoil and breakdowns. Performance artist Bobby Baker has claimed that the struggle of working so many hours for an unstable income led to her breakdown. Artists are often idolised, but not paid well for this idolisation. Baker would paint watercolours of her standing on the edge of a cliff during her darkest moments. Her daughter later revealed that she found these images comforting; to her it meant her mother was using an outlet for her feelings that didn’t involve actually going and standing on the edge of a cliff. We all have ideas and thoughts that are unacceptable, and artists ‘speak’ these thoughts. Baker describes the ‘nutty’ artist, who represents what we are scared to see in ourselves.

Being an artist is not just an occupation, often, it is what makes a person who they are. This can become all consuming. But we, as art viewers, can learn to live and understand ourselves through the work of artists. Art has the ability to help us deal with our lives; it goes on transforming, and it goes on being ‘new’. The ability to create, Kennedy claims, is not something restricted to the ‘mad’, it is in fact something for everyone. Through art we can change the story – we can see the light instead of the dark. It can help us be here, and be alive.

The BBC programme can be found at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01ghb93