‘Outsider art’ in the traditional sense – i.e. Jean Dubuffet’s description – alludes to an isolated artist, working on the periphery of the mainstream art world. Contrary to this controversial belief, many of the most notable ‘outsider artists’ of the twentieth century were supported, encouraged and ‘outed’ by some of the most famous ‘mainstream’ artists of the same century. This series of blog posts will highlight a few of these relationships, in the hope of rectifying the general thought that artists that often sit under the umbrella of ‘outsider art’ were completely immune to and separate from the twentieth century ‘mainstream’ art world. In fact, many of the ‘masters’ of modern art were hugely influenced by these relationships.

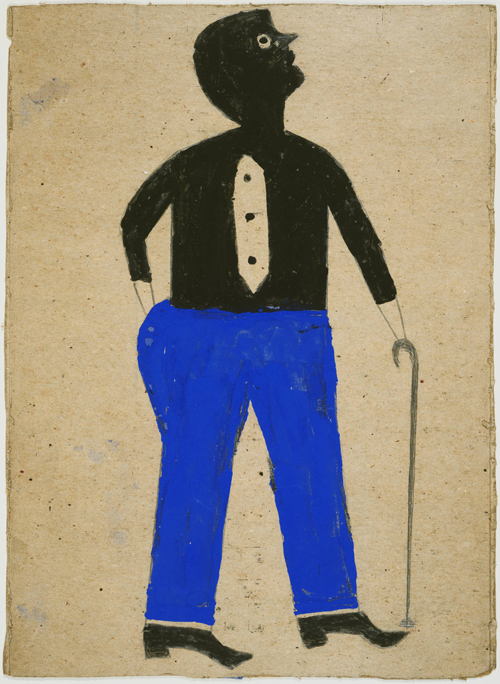

#1 Bill Traylor and Charles Shannon

#2 Alfred Wallis and Ben Nicholson

# 2: Alfred Wallis and Ben Nicholson

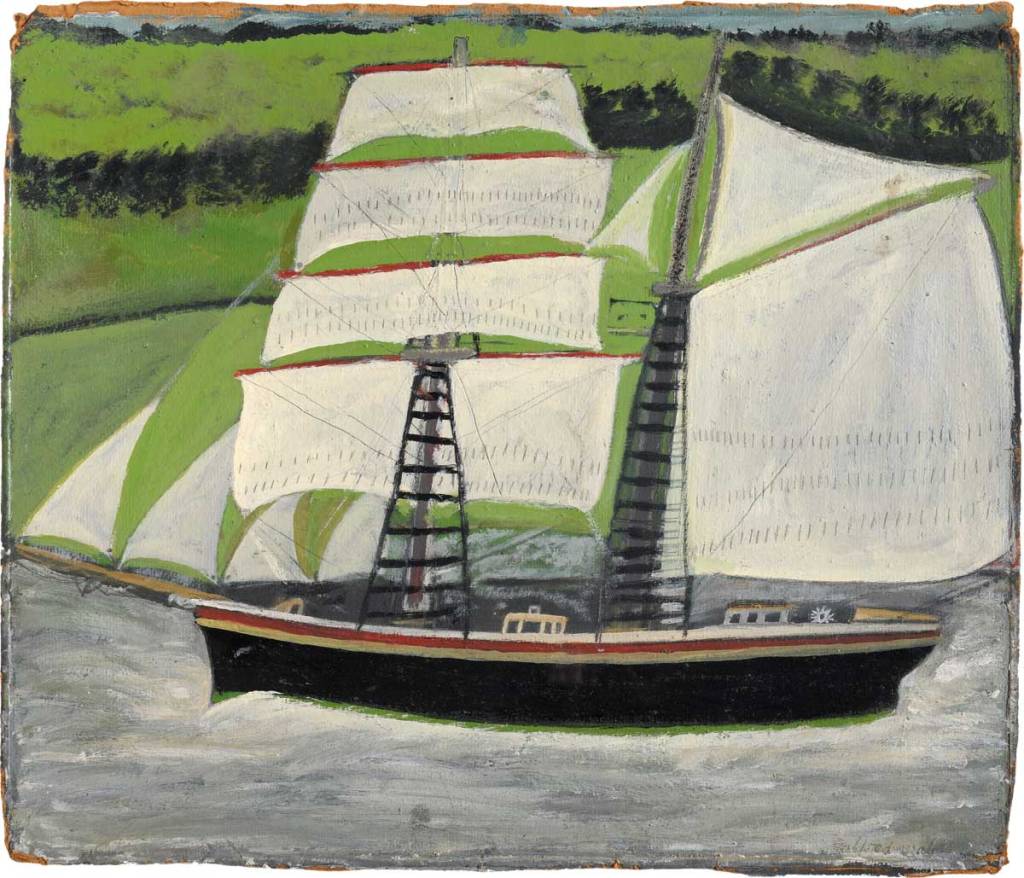

In St. Ives in 1928 came another chance meeting of two celebrated twentieth century artists – that of self-taught Cornish fisherman Alfred Wallis (1855 – 1942) and modern favourite, Ben Nicholson (1894 – 1982). This union occurred when Nicholson and a friend, Christopher Wood, came across Wallis’s paintings nailed to a wall beside an old fisherman’s cottage during a visit to the area. Nicholson saw in Wallis’s work what he wanted to achieve in his own – a certain fresh naivety. Nicholson documented their meeting: “On the way back from Porthmeor Beach, we passed an open door in Back Road West and through it saw some paintings of ships and houses on odd pieces of paper and cardboard nailed up all over the wall, with particularly large nails through the smallest ones. We knocked on the door and inside found Wallis, and the paintings we got from him then were the first he made.”[1]

Much like Bill Traylor, Wallis is another artist who discovered his creative side later on in life, at the age of 68 after the death of his wife. In his earlier years, it is thought that Wallis went to sea as a fisherman – possibly even from the age of nine. Taking up painting after his retirement from a shop selling salvaged marine goods in St. Ives, Wallis used old torn boxes and ship paints to create his masterpieces.

In an article authored by Nicholson in 1948, the artist compared Wallis’s style of working to that of Paul Klee:

“He would cut out the top and bottom of an old cardboard box, and sometimes the four sides, into irregular shapes, using each shape as the key to the movement in a painting, and using the colour and texture of the board as the key to its colour and texture. When the painting was completed, what remained of the original board, a brown, a grey, a white or a green board, sometimes in the sky, sometimes in the sea, or perhaps in a field or a lighthouse, would be as deeply experienced as the remainder of the painting.”[2]

Wallis’s works are incredibly evocative of what we now see as a self-taught, uninhibited, and untutored style. He largely ignores perspective and often, the objects depicted will vary in size depending on how much importance the artist gave to them.[3]

Michael Glover, writing for the Independent during a joint exhibition celebrating the works of both Wallis and Nicholson at Compton Verney in 2011, speaks of Nicholson’s behaviour towards the older artist: “He began to patronize the old man, and to buy his paintings for the price of a meal or two. After he returned to his smart home in London, Wallis continues to send him batches, bound up with string and brown paper. Nicholson’s friends bought them too. Wallis began to be lionised a bit by the London avant-garde – Herbert Read and his friends.”[4]

Nicholson’s interest in Wallis didn’t bring his work great recognition during his lifetime – Wallis continued to live in poverty after the meeting, despite Nicholson’s valiant attempts to promote the self-taught artist’s work and bring it to the attention of the burgeoning modern art scene. We know now, however, that that fateful chance meeting between the two – patronising aside – would in fact set the older artist up to become recognised as one of the most prolific and original 20th Century British artists. His unique ‘primitive’ portrayal of boats and ships provided inspiration to many artists, and his work is undoubtedly considered highly influential in the development of British Modernism.

- Alfred Wallis, ‘House at St. Ives’

‘Relationships’ series:

#1 Bill Traylor and Charles Shannon

#2 Alfred Wallis and Ben Nicholson

References

[1] Cornwall Calling

[2] Ben Nicholson, ‘Alfred Wallis’ in Horizon, Vol. VII, No. 37, 1943

[4] Michael Glover, ‘Alfred Wallis and Ben Nicholson, Compton Verney, Warwickshire’ . 31 March 2011 [Available Online]