In light of his two current exhibitions in London, Julio Cesar Osorio talks about finding inspiration in the darkest of places and his want to portray his own unique journey, inviting the viewer to jump in and join him – not unquestioningly – on his travels to a more vibrant world.

When did you first start making art?

Looking back at my life I can honestly say that I have always been very analytical about my surroundings. I have always looked for the beauty within things; even at a microscopic level, like when I looked at an onion skin under a microscope for the first time in biology class and thought that the shapes and patterns looked lovely. I have always visually admired things, but it wasn’t really until I landed in prison that I took up art. From the word go I was over taken by the therapeutic power of painting; it became my passion and provided an escape from where I was.

What originally inspired you, and what inspires you now?

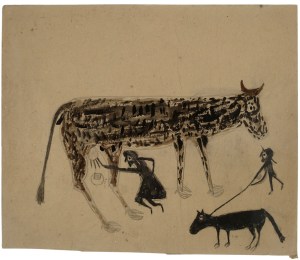

I did a degree in photography and digital imaging 15 years ago and during that time Dali became my inspiration to create surreal work; to carve one’s own story to illustrate what’s on one’s mind. This was exactly what I did when I discovered that I could paint in prison. This would be the tool I would use to create – even in the environment I was in.

To this day, surrealism has been the genre I have chosen to work in and a surrealist is the type of artist I wish to be classed as.

What is your process – from starting to finishing? How long does it take?

I write down ideas or do small sketches of what the idea involves, and then look for relevant imagery; photos, magazine cuttings, etc., that I think might work in my painting and then I’ll start by painting the background. Then I’ll move on to sketch the subject matter, making sure it’s all in the ideal place and when I’m happy with the layout, I’ll go on to paint them.

Each piece has varied in the time it’s taken to produce. Most of my work was produced in prison, where I became so prolific that I would work at least 10 hours a day seven day a week. As a result, I would produce at least two pieces a month. Since my release in September 2013, I have only produced one 190 x 190cm painting completed over a period of one year.

What do you hope viewers get from your work?

I produced all of my work and honed my skills in prison. I used the medium of painting to transport my mind with the goal of taking the viewer on my journey, encouraging them to place themselves in the work, to read and question all the thoughts and feeling that I used in every one of my pieces.

What are you working on at the moment?

At present I am working on promoting my work and my name through social media, and I am preparing a marketing strategy to generate sales.

I am also working on a series of photographs that I have of body painting on females. I am adding paint to these so they become mixed media pieces.

Tell us a bit about your current exhibitions?

At present I have got two exhibitions running concurrently in two different parts of London looking at two different themes.

See Julio Cesar Osorio’s work in London…

The Communication of Colours from a Very Dull Place

Until 31st January at Coffee Wake Cup, 14 Clapham Park Road, London, SW4 7BB. Open daily from 7am – 7pm.

Concentrating on the use of colours in the works on display and how Julio used them vibrantly whilst in prison; a very dark and dull environment. Julio wanted to show the polar opposite of what he was experiencing at the time.

The Artist’s Subconscious

Until 31st January at Freud Bar/Gallery, 198 Shaftesbury Avenue, London, WC2H 8JL.

“The liberty of the individual is no gift of civilisation. It was greatest before there was any civilisation.” – Sigmund Freud.

This exhibition concentrates on Julio’s works that evolved from his inner thoughts during his time in prison.