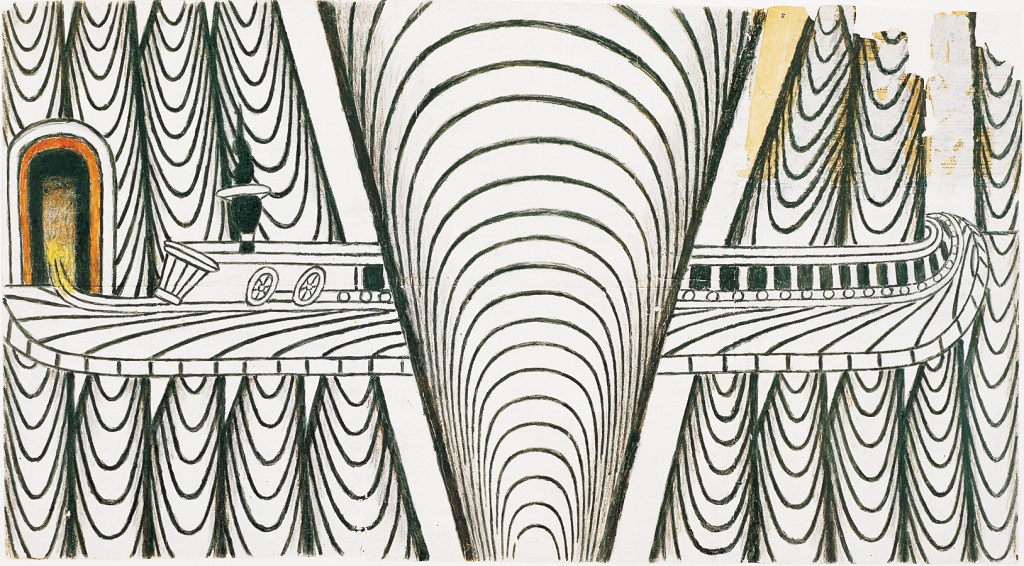

Above image: Henry Darger

Happy New Year everyone – I hope you are all enjoying what 2014 has had to offer so far. I thought I would do a bit of an off the cuff ‘rambling’ blog post talking about a couple of ideas I have recently had relating to the term ‘outsider art’. Hopefully you will share your ideas and opinions on these below.

The festive period brought a bit of a break from blogging and the art world in general, so, as I rekindled old and started new conversations about ‘outsider art’ in the new year, I had some fresh ideas that I wanted to share with you. The first came to me earlier in the week, when I was thinking about how I would now – two years on from starting the blog – describe the term ‘outsider art.’ This is an art that categorically comes from within, an art that (according to Dubuffet) isn’t influenced by art history or external factors. Despite my absolute disagreement with this idea of Dubuffet’s, I do believe that one of the reasons I am so drawn to ‘outsider art’ is because it epitomises raw communication from the heart and soul. Why then, do we call it ‘outsider art’ – shouldn’t it be ‘inside art’ or ‘art from within’? It seems absurd to me, as someone who enjoys using words, that the term itself should be so contradictory to the work caught beneath this umbrella.

Often, when I tell people that I write about ‘outsider art’, they’ll ask: “Is that open-air art?” Hmm, it would make sense, wouldn’t it? I think someone also shared this opinion on BBC Imagine’s recent programme dedicated to ‘outsider art’; ‘Turning the Art World Inside Out’ (I think you can still catch it here on Youtube). So why, I wonder, can’t we give it a more deserving, fitting, and altogether less controversial name? ‘Art from within’ or ‘Inside’ art might go some of the way to distilling visions of the ‘societal outsider’ and alleviate the current separation between ‘outsider art’ and the ‘mainstream’ art world. Or, to play devil’s advocate, do we even need a label at all? I’m not so sure any more… Let me know what you think.

The second thing I wanted to write about stems from a conversation I had on a recent visit to a prison. I was asked how artists who are also offenders or ex-offenders could ever shake the label of being an offender or an ex-offender if they are continuously associated with organisations who are known to work with these groups. This is something I have thought about previously, but to have someone who is potentially in that position to voice their concerns made me re-evaluate its importance. I know a lot of fantastic organisations working with ‘marginalised’ groups, but I wonder if perhaps there is something in this idea that people don’t want to be associated with their past or known by one label that doesn’t encompass everything they are or can be. For example, if art is marketed as ‘offender art’, does that mean the creator’s image is tainted; that they are not seen simply as an artist working within the art world?

I have always wanted ‘outsider art’ to be exhibited and publicised in a way that eliminates in-depth biographies, and instead just focusses on the art as a captivating piece of work created by a talented individual. There are plenty of organisations operating across the country that do a fantastic job in supporting artists who are perhaps facing barriers to the ‘mainstream’ art world for whatever reason, and I think that these charities and groups are undoubtedly needed; in particular to encourage and nurture an artist’s first steps into, or a return to, the art world. The conversation in the prison concluded with a suggested solution that these organisations are invaluable as a springboard towards a career as an artist. By becoming an artist unwanted labels can be lost; replaced, if necessary, with more favourable and accurate ones.

I would really value and appreciate your ideas on either of these thoughts, so please post any comments below. Happy New Year!