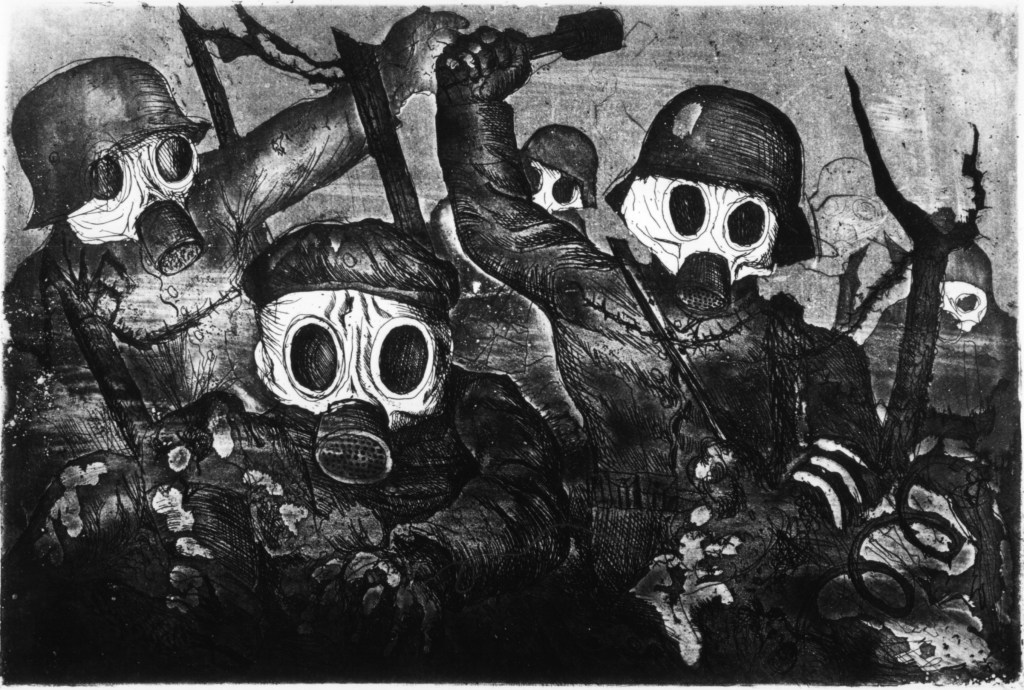

Above image: Otto Dix, Sturmtruppe geht unter Gas vor (Stormtroops advancing under a gas attack), 1924 [Courtesy of: lewebpedagogique.com]

I recently visited an exhibition of German artist Otto Dix’s series of prints entitled Der Krieg (The War) at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill, East Sussex. I studied this series for my undergraduate dissertation a while back; where I focused on the links between German Expressionism and Outsider Art – more specifically the impact that experiences such as war can have on our mental health and how this makes the distinction between Outsider Art and ‘other’ art movements ever more intangible.

During the First World War Dix volunteered to join the German army and was assigned to a field artillery regiment in Dresden. He took part in the Battle of the Somme before being transferred to the Eastern Front. He then returned to fight on the Western Front in 1918. In this year, he was wounded in the neck before being discharged from service in the December. His exposure to warfare had a profound impact, resulting in recurring nightmares in which he crawled through destroyed houses.

![Otto Dix, Schädel (Skull), 1924 [Courtesy of: www.deborahfeller.com]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/the-skull-1924.jpg?w=766&h=1024)

“For all its waste, the war provided a windfall for scavengers. The First World War produced generations of happy worms and maggots. Trench rats roamed as big as beavers. Gas was sometimes a welcome respite as it decimated these pests.”

– Taken from Otto Dix: Der Krieg exhibition pamphlet from the De La Warr Pavilion.

Between 1915 and 1925, Dix created a significant group of paintings as a way of coming to terms with his harrowing wartime experiences. He began painting in a new style; a style which combined certain stylistic tropes and aspects of both Futurism and Expressionism, and in 1924 he produced Der Krieg – a collection of fifty etchings and aquatints. The series is possibly one of the greatest anti-war depictions ever to be made, and is often compared to Francisco Goya’s Los Desastres.

This idea of the depiction of destruction and trauma as a source of creative impulse was widely common during the years following the First World War, resulting in a different kind of Expressionism emerging within Germany. At this time, there was a clear shift from a primitive, nostalgic, almost disengaged pre-war Expressionism, to a much angrier, political, ravaged Expressionism in the years following the First World War. Expressionist artists at this time seemed – quite understandably – engulfed by a ‘madness’ brought on by the normalisation of warfare and everything that came with it.

Notably, in 1937, Dix’s work was included in the Nazi generated Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition in Munich. Even before the party had come to power in 1933, they had begun comparing images by avant-garde artists with those of the ‘clinically insane.’ Paul Schultze-Naumburg, a Nazi architect, was well known for contrasting the works of modern artists, such as Emil Nolde, with photographs of patients with physical disabilities with the intention of proving that modern art was pathological and degenerate.[1]

The Nazis used modern art; Cubist, Expressionist and Dadaist works amongst others, as a scapegoat for the country’s economic collapse – a supposed conspiracy by Communists and Jews, and instead attempted to bring the focus of art back to the ideals of the human body.[2]

“A trench soldier quickly gulps a meal in the company of a human skeleton trapped in the frozen landscape beside him.”

– Taken from Otto Dix: Der Krieg exhibition pamphlet from the De La Warr Pavilion.

July 19 1937 in Munich: more than 650 paintings, sculptures and prints taken from large German public collections were put on display with the aim of showing the German population what kind of art was to be considered inherently ‘un-German.’ Both abstract and representational works, including pieces by Dix, were condemned – as were the attempts to combine art and industry that had been pioneered by the Bauhaus artists. The exhibition, however regrettably, has made a place for itself as the most visited and viewed exhibition of modern art, with two million visitors in Munich, and a further one million viewers as it travelled across Germany and Austria.

The works of George Grosz and Dix – and Expressionism more generally as a movement – were singled out to exemplify the idea of degeneracy within modern art.[3] Dix was particularly condemned due to his ‘defeatist’ attitude towards the war. His paintings The Seven Deadly Sins (1933) and The Triumph of Death (1934) portray the dangers of Nazism, and because of this, he was treated with utmost suspicion throughout the Third Reich.

The Nazis saw ‘degenerate’ art as a “metaphor of the madman as the artist,” with Adolf Hitler developing a dialogue that insinuated that the avant-garde artist should be considered as an ‘outsider.'[4]

![Otto Dix, Gastpte - Templeux-la-Fosse, August 1916 (Gas Victims - Templeux-la-Fosse, August 1916), 1924 [Courtesy of: www.port-magazine.com]](https://kdoutsiderart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/gas-victims.jpg?w=640&h=460)

“By 1924, people were aware of the horrors of gas but censored wartime reporting spared many from its ghastly details. Here the results are depicted with raw clarity of someone who was there. Indeed, much of Der Krieg was based on Dix’s wartime diary drawings. Many were probably struck by the appearance of the victims, darkened for lack of oxygen and the nonchalance of the medical staff who had seen it many times before.”

– Taken from Otto Dix: Der Krieg exhibition pamphlet from the De La Warr Pavilion.

A certain political and social ‘madness’ continued for the people of Germany throughout the reign of Hitler and his National Socialist Party. The extermination of German citizens based solely on race, ethnicity or religion was widely executed, as well as the mass rejection of works by some of the leading avant-garde artists. The whole era was epitomised by what defined ‘madness’, with the line between the ‘sane’ and ‘normal’ – if we are even able to define these terms – and that of the ‘pathological’ becoming increasingly blurred.

The work of the German Expressionists, and the artists themselves, may have been deemed ‘insane’ by many critics at the time, but, as Jean Dubuffet claims, “very often the most delirious, most feverish works, those that are apparently stamped most clearly with the characteristics ascribed to madness, have as their authors people considered as normal.”[5]

Annette Becker, writing in The Avant-Garde, Madness and the Great War, claims that “there is hardly more sense in the claim that there is an insane art as there is a dyspeptic art, or the art of those with knee troubles.”[6] Jon Thompson, curator of the Inner Worlds Outside exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, London in 2006 insinuates that “all human minds are fundamentally the same,” we are all the product of modernity and, influenced by Marx he “speaks to the degrees to which we are all alienated in one way or another, or in many ways at once.”[7] German Expressionism – and the work of Dix – was essentially a product of its time; a time that was characterised by alienation, discontent and the ‘madness’ of political instability and mechanical warfare.

Otto Dix: Der Krieg continues at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill until 27 July 2014. Click here for more information on the exhibition.

References

[1] Berthold Hinz, “‘Degenerate’ and ‘Authentic’: Aspects of Art and Power in the Third Reich,” Art and Power: Europe under the dictators 1930 – 45. Eds. Ades, Dawn, Tim Benton, David Elliott and Iain Boyd White, The Southbank Centre, 1995.

[2] Stephanie Barron, ed. German Expressionism 1915 – 1925: The Second Generation, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988.

[3] Hinz, “‘Degenerate’ and ‘Authentic’: Aspects of Art and Power in the Third Reich.”

[4] Sander Gilman, “The Mad Man as Artist: Medicine, History and Degenerate Art,” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 20, No. 4 (1985): p594

[5] David Maclagan, Outsider Art: from the Margins to the Marketplace, Reaktion Books, 2009: p38

[6] Annette Becker, “The Avant-Garde, Madness and the Great War,” Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 35, No. 1 (2000): p81

[7] Adrian Searle, Meet the Misfits